The politics of Pop Art: A dissenting world view

17 September 2015

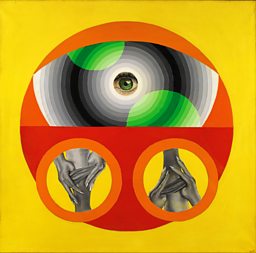

If you thought Pop Art was just an Anglo-American phenomenon, The World Goes Pop at London’s Tate Modern will make you think again. Contrary to popular misconception, Pop Art wasn’t confined to the United States – or the United Kingdom, for that matter. It was a global revolution, and in every country it was different. WILLIAM COOK considers a dynamic show which uncovers the sometimes darker and more subversive aspects of Pop Art worldwide.

Tate curators Jessica Morgan and Flavia Frigeri have travelled the world to find the forgotten voices of the global Pop Art movement, and brought together 68 artists from 28 nations.

It was the camouflaged way I found to speak out against the military regimeMarcell Nitsche

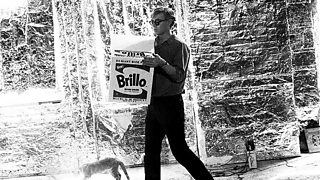

European Pop Artists were far more political than their American or British counterparts. While Peter Blake basked in warm nostalgia and Andy Warhol anatomised bland celebrity, European artists attacked American militarism.

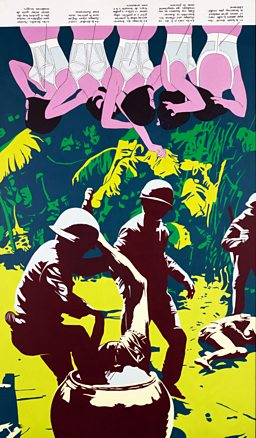

Finland’s Raimo Reinikainen subverted the star spangled banner with photos of American atrocities in Vietnam. ‘At last, a Silhouette Slimmed to the Waist’ by French artist Bernard Rancillac, shows female torsos clad in corsets, above US troops humiliating a soldier of the Viet Cong.

Pop Artists were equally eloquent in their opposition to the repressive juntas of South America. Brazilian Marcell Nitsche built a huge papier mache hand, wielding an enormous fly swatter. ‘It was the camouflaged way I found to speak out against the military regime,’ he explains.

Censorship made artists more ingenuous. Compared to written artforms, like novels, plays and poetry, Pop Art was relatively difficult for the authorities to control.

At Last, A Silhouette Slimmed to the Waist juxtaposes two images top to tail and can be hung either way, in order to emphasise either the advertisement for female underwear or the horrors of the Vietnam WarElsa Coustou for Tate, September 2015

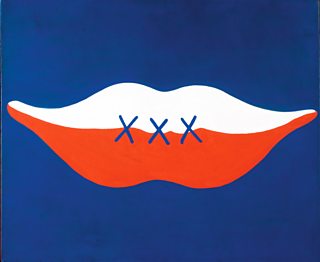

These artists didn’t just attack the right. Some of the most powerful artworks in this show criticise Communist suppression in Eastern Europe. The Smile by Poland’s Jerzy Ryszard Zielinski is a painting of a pair of lips, tightly sewn together.

As Spanish women we suffered from double repression. The politics imposed by the dictatorship, and the inequality towards womenAngela Garcia

Without Rebellion depicts a giant tongue, nailed to the floor. Sadly, Zielinski didn’t live to see the resumption of free speech in his homeland. He died in 1980, aged just 37.

A number of these artists died young: four in their twenties and thirties, four more in their forties. However a fair few of them are still around and for these survivors, The World Goes Pop is a belated but richly deserved accolade. Few of these artists are familiar outside their native or adopted countries. A good many are virtually unknown back home.

Why is their work so unfamiliar? Unlike a lot of modern art, it’s entertaining and accessible. Despite its foreign origins, it’s easy to understand.

But making provocative art in totalitarian dictatorships is hardly a simple route to fame and fortune. Labouring under Communism and Fascism, it’s a wonder that these artists, and so many of their artworks, survived.

Another reason is that most of these artists are female. ‘As Spanish women we suffered from double repression,’ reveals Angela Garcia, who was born in Valencia in 1944, and grew up under Franco. ‘The politics imposed by the dictatorship, and the inequality towards women.’

‘If it was a choice between a male artist and a female artist, the male artist was almost always chosen, regardless of the quality of the work,’ concurs co-curator Jessica Morgan.

Refreshingly, three quarters of the artists in this show are women, redressing an imbalance that’s persisted in Pop Art and elsewhere.

Surprisingly, there wasn’t much communication between Pop Artists in different countries, even neighbouring countries, but it’s fascinating how often they came to similar conclusions.

Ruth Francken’s Man Chair sprouts arms and legs. So does Marta Minujin’s Mattress. These sculptures were made a continent apart, in Czechoslovakia and Argentina.

The Sixties was the best and worst of times, and Pop Art was its perfect form of self-expression: brash but seductive, like the consumerism it mimicked.

So why does the myth persist that Pop Art was purely Anglo-American? Partly lazy insularity, and partly the power of the written word. The first (and most influential) books about Pop Art were published in America in the 1960s, and though they featured a few British artists, artists from beyond the Anglosphere were ignored.

There was no attempt subsequently to try and rethink what that story might have been. It’s very difficult to rewrite that storyJessica Morgan, co-curator, The World Goes Pop

These books set the pattern for future scholarship. ‘There was no attempt subsequently to try and rethink what that story might have been,’ says Morgan. ‘It’s very difficult to rewrite that story.’ However her show has succeeded.

Upstairs, on the fourth floor, Tate Modern have mounted a parallel display of Pop Art from the Tate’s permanent collection: familiar classics by Americans like Jasper Johns and Roy Lichtenstein, and Britons like David Hockney and Richard Hamilton.

Of course these are brilliant paintings, and the Tate would be much poorer without them, but after viewing the rediscovered artworks on the floor below, they all seem rather tame.

The World Goes Pop is at Tate Modern, London, 17 September to 24 January 2016

Related Links

Exhibition Images

Pop Art Features

-

![]()

The Politics of Pop Art

A dissenting view from the global artists represented at The World Goes Pop exhibition at Tate Modern.

-

![]()

Pop Art's Road Trip

Alastair Sooke on the stark, understated gas station photographs of Ed Ruscha.

-

![]()

Did Scottish artists invent Pop?

Can Pop Art really trace its origins to the work of a couple of artists from Scotland?

-

![]()

Sun Kings

Stephen Smith compares the courts of Andy Warhol and the original Sun King, Louis XIV - with the Factory as a 1960s Versailles.

-

![]()

Pop Idents by Pop Icons

Watch the BBC Four Goes Pop! channel idents by Peter Blake, Derek Boshier & Peter Phillips.

-

![]()

What's Andy Doing Right Now?

Find yourself in the midst of a typical day for Pop Artist Andy Warhol in the mid-1960s.

-

![]()

Warhol's Polaroids

The genius behind the camera that enabled Andy's instant celebrity obsession.

-

![]()

The Power of Desire

Controversial British Pop Artist Allen Jones is the guide around his Royal Academy exhibition.

-

![]()

Dividing Opinion

A Career in Quotes: What the critics said about controversial British Pop Artist Allen Jones.

-

![]()

24 Hours with Andy Warhol

Follow Andy and his entourage as they tour London in 1970, meeting David Hockney and film critic Dilys Powell.

-

![]()

Cheese!

A fascinating look inside The Factory in 1965, as filmmaker and activist Susan Sontag visits while Andy is filming.

-

![]()

Cover Star

When Everyone Could Own a Warhol: Andy Warhol's 1950s album covers for hip jazz labels such as Blue Note.

-

![]()

Superstars & Silver

The Factory 1964-1970: Billy Name's iconic images of Warhol's Silver Factory, with the Velvets, Nico, Warhol superstars & Dali.

-

![]()

Heroes of German Pop

William Cook on the exquisite colours of German Pop at an exhibition in Frankfurt.

-

![]()

German Pop: In pictures

Artworks from the bold and brilliant pioneers who shaped Germany's 1960s pop art scene.

-

![]()

Transmitting Warhol

A video tour of last year's Andy Warhol exhibition at Tate Liverpool.