Did Scottish artists invent Pop art?

By JOHN-PAUL STONARD | 19 August

A classic American art movement popularised by Andy Warhol, can Pop art really trace its origins to the work of a couple of artists from Scotland?

Here's a theory: Pop art was invented in Scotland. Quite a wild hypothesis, it might be said.

Pop art, so the standard story goes, first appeared in London in the mid-1950s, among a dynamic group of young artists and thinkers known as the Independent Group, who met at the Institute of Contemporary Arts.

'Pop art' was coined by an English art critic, Lawrence Alloway

Among the key figures were the artists Richard Hamilton, Eduardo Paolozzi and John McHale, and the theoreticians Lawrence Alloway and Reyner Banham.

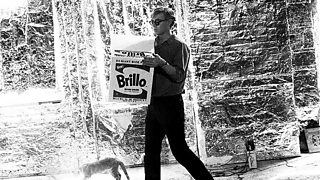

At the same time Pop art was being forged in a different way in America, in the work of Roy Lichtenstein and Andy Warhol.

Artists in Germany, France and elsewhere soon picked up on the new spirit but it was the London lot who seemed to have got there first.

The term itself, 'Pop art', was coined by an English critic, Lawrence Alloway (there are the inevitable disputes about this).

So what has Scotland got to do with it?

For a start, it was a couple of Scottish-born artists who were at least two-thirds of the horsepower that powered British Pop; John McHale (born Maryhill, Glasgow, 1922), and Eduardo Paolozzi (born Leith, 1924, to Italian parents).

McHale is the lesser-known of the two, partly a result of the fact that he moved to America in the early 1960s and ceased working as an artist.

During the previous decade, however, he made a series of pioneering collages using images torn from illustrated magazines.

The best-known, Machine Made America II, (1956) was reproduced on the cover or Architectural Review, which was edited by Ian MacCallum (another 'phenomenally stylish Scot' in the words of Rayner Banham).

McHale's treasure trove of Americana was the real instigation for the Pop art images that burst onto the scene in the 1956 exhibition This is Tomorrow

It was less however for his collages than for his wide-ranging interests, and receptiveness to new subjects for art, that McHale was truly a Pop progenitor.

He studied at Yale for a year, under the famous artist and educator Joseph Albers, and returned to London with a treasure trove of Americana — Elvis Presley records, Mad Magazine, and a trunkful of glossy magazines such as The Ladies Home Journal, Fortune, and Life... highly exotic items.

These were the real instigation for the Pop art images that burst onto the scene in the 1956 exhibition This is Tomorrow, held at the Whitechapel Gallery.

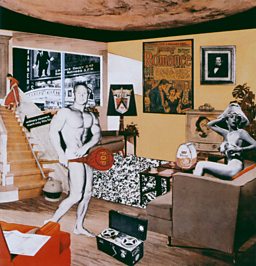

It was in this exhibition that (as a reproduction), Richard Hamilton's famous collage Just what is it that makes today's homes so different, so appealing? (1956) first appeared. The quintessential work of Pop art, it shows a modern Adam and Eve surrounded by the paraphernalia of a consumer paradise.

Hamilton made Just what is it...? using magazines from McHale's treasure chest, and was inspired by McHale's enthusiasm for this new world of images. McHale was, as Richard Hamilton put it, a 'master angler', who 'fished in any and every water and brought his catch to table at the ICA'.

Born and brought up in Edinburgh, Eduardo Paolozzi played an equally (if not more ) important role in the birth of Pop art. Although he grew up in the Italian immigrant community on the outskirts of Edinburgh, anybody who heard him talk would not mistake his strongly Scottish upbringing.

The collages he made in the late 1940s, known as the 'Bunk' series, are dazzling concoctions from diverse sources, particularly American magazines.

Artists from Scotland, and Glasgow especially, are reinventing contemporary art at every turn

They were the first true works of Pop art (one even including the word 'Pop'), but were also a direct continuation of the scrapbooks he kept as a child, which were filled with cigarette card images and the brightly coloured wrapping from his father's sweet shop.

Paolozzi carried on making the collages while staying in Paris in the late 1940s (many British artists went at this time to escape the dreariness of post-War London), and showed them for the first time at the ICA on his return, in the form of a rambunctious slide lecture notorious as the first public outing for Pop art in Britain.

McHale and Paolozzi, both originating north of the border, were two of the most important figures in the emergence of Pop art during the fifties. So can we say that Pop art was a Scottish invention?

Well perhaps that is not the best question to ask - neither movements nor works of art are invented, but rather just appear at a certain time and place, the result of a certain convergence of things.

Forged in the work of McHale, Paolozzi and Hamilton, Pop art was the result of the convergence of American culture on London in the early 1950s. The young artists associated with the ICA realised the growing power of commercial culture, and wanted both to reflect on it and rival it in their art.

But Pop art was also a reflection of Paolozzi and McHale's earlier formative experiences, and what might be seen as a particular Scottish understanding of the vernacular.

Some of the first theories about popular culture arose at the time of the Scottish Enlightenment, in the writings of Adam Smith, who noted the significance of 'publick diversions', and the important place of a new popular urban culture.

Coupled with a lively critical spirit, and a willingness to cut through the snobbishness associated with high art (Scottish qualities, it might be suggested), we seem to have all the preconditions for Pop.

So perhaps it is not such a wild hypothesis after all. What can be said with certainty is that nowadays artists from Scotland, and Glasgow especially, are reinventing contemporary art at every turn; you only have to look at the recent years of the Turner Prize.

If Pop art were born again today, there seems little doubt that it would be invented in the painting studios of the Glasgow School of Art.

Related Links

Pop Art Features

-

![]()

The Politics of Pop Art

A dissenting view from the global artists represented at The World Goes Pop exhibition at Tate Modern.

-

![]()

Pop Art's Road Trip

Alastair Sooke on the stark, understated gas station photographs of Ed Ruscha.

-

![]()

Did Scottish artists invent Pop?

Can Pop Art really trace its origins to the work of a couple of artists from Scotland?

-

![]()

Sun Kings

Stephen Smith compares the courts of Andy Warhol and the original Sun King, Louis XIV - with the Factory as a 1960s Versailles.

-

![]()

Pop Idents by Pop Icons

Watch the BBC Four Goes Pop! channel idents by Peter Blake, Derek Boshier & Peter Phillips.

-

![]()

What's Andy Doing Right Now?

Find yourself in the midst of a typical day for Pop Artist Andy Warhol in the mid-1960s.

-

![]()

Warhol's Polaroids

The genius behind the camera that enabled Andy's instant celebrity obsession.

-

![]()

The Power of Desire

Controversial British Pop Artist Allen Jones is the guide around his Royal Academy exhibition.

-

![]()

Dividing Opinion

A Career in Quotes: What the critics said about controversial British Pop Artist Allen Jones.

-

![]()

24 Hours with Andy Warhol

Follow Andy and his entourage as they tour London in 1970, meeting David Hockney and film critic Dilys Powell.

-

![]()

Cheese!

A fascinating look inside The Factory in 1965, as filmmaker and activist Susan Sontag visits while Andy is filming.

-

![]()

Cover Star

When Everyone Could Own a Warhol: Andy Warhol's 1950s album covers for hip jazz labels such as Blue Note.

-

![]()

Superstars & Silver

The Factory 1964-1970: Billy Name's iconic images of Warhol's Silver Factory, with the Velvets, Nico, Warhol superstars & Dali.

-

![]()

Heroes of German Pop

William Cook on the exquisite colours of German Pop at an exhibition in Frankfurt.

-

![]()

German Pop: In pictures

Artworks from the bold and brilliant pioneers who shaped Germany's 1960s pop art scene.

-

![]()

Transmitting Warhol

A video tour of last year's Andy Warhol exhibition at Tate Liverpool.