Maggi Hambling on Rembrandt

21 October 2014

Rembrandt doesn't flatter and he doesn't make judgements

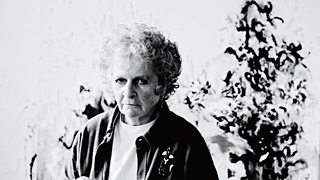

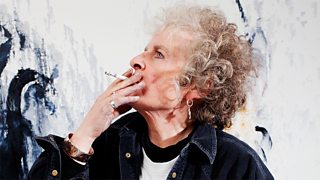

MAGGI HAMBLING CBE is one of Britain's most significant living painters and sculptors and she was the first National Gallery Artist in Residence from 1980-81. Rembrandt is one of her favourite artists of all time. BBC Arts asked Hambling to choose five outstanding works from the Dutch master.

"Rembrandt paints more movingly than possibly any other painter who has ever lived. He doesn't flatter and he doesn't make judgements. He paints 'what is' but with such compassion that it takes 'what is' onto another level.

I've chosen five paintings from different periods of his life. When you see Rembrandt's work, it's as if you go through his life with him and, by identification, your own life."

Self-portrait (1628)

Panel, 22.6cm x 18.7cm

This was painted when Rembrandt was 22. At the time it was a very radical portrait and it foreshadows what was to come in his very grand and meaningful use of light and dark.

The mystery is already there – the face is more than half veiled in shadow as if he is still a mystery to himself. A portrait is a conversation and a confrontation.

You can go back to a Rembrandt throughout your life and let it talk to you whereas a lot of art nowadays you only need to see for a few seconds.

A Woman Bathing in a Stream, 1654

Oil on oak, 61.8 x 47 cm

This is generally reckoned to be Hendrickje Stoffels, Rembrandt's mistress. It's a very sexy painting - the marvellously loosely-painted shift she is wearing just covers the top of her thighs.

Women were women then - they weren’t sticks - and she's pretty voluptuous. The contrasts in the handling of the paint are terrific: the legs, the arms, the hands and the beginning of the breasts are very sensual and fleshy, and the cover up is merely strokes of paint.

The viewer becomes Rembrandt himself, feasting his eyes on his mistress paddling in a pool. He gives you the feeling that the painting is being made in front of your very eyes.

One of the great things about Rembrandt is that the subject flowed through him and out through his hands and the paint. Everything there has been dictated by the subject. That's a crucial point about great art; when something bigger than the artist – and outside of the artist - is in charge of things.

The Anatomy Lesson of Dr Joan Deijman, 1656

Oil on canvas, 100 x 134 cm

There's an extraordinary foreshortening in this painting, which makes you feel that the body is being cut up right in front of you.

It's completely real - the big feet come right at you. It's painted with such empathy and there's such calm about the operation that's going on, even though it's obviously very bloody.

Again the use of light and dark is crucial – the huge light falling on the body surrounded by comparative darkness. By this time in Rembrandt's life the paint is flowing and dissolving in the most amazing way.

Self-portrait as Zeuxis Laughing, 1663

Oil on canvas, 82.5 x 65 cm

If I could have one painting in the world it would be this one. The paint is going at 100mph and it's completely fluid and totally compelling.

Here is Rembrandt as a much older man having lived a dramatic life - being rich, being poor, being broken-hearted - but he's still laughing at himself and laughing with us.

It's a heroic painting. I have a rather ropey old postcard of this painting that I bought years ago in Cologne and which is always on my studio wall next to me.

The Return of the Prodigal Son, 1667-1669

Oil on canvas, 262 × 206 cm

I first saw this painting in reality last year when I had a show at the Hermitage and stood in front of it over and over again. Every painting is about one moment but here, because that one moment is painted so magically, time is eradicated.

The prodigal son has his back to us, one filthy foot showing, and the diamond shape of his father's arms enclose him and hold him safe. The use of light and dark is eloquent.

It's as if the prodigal son's father is God the Father and you feel as though you're being forgiven yourself. It was painted in the last couple of years of Rembrandt's life and there's the whole of time in that one moment of forgiveness and compassion.

With paintings, drawing and prints so much comes down to the human touch - whether it's a brush dipped into ink or a knife with oil paint on it. The physicality of everything Rembrandt did is there and happening in front of you. Looking at reproductions on a computer screen is nothing like experiencing the real thing.

Emptying yourself before you stand in front of a masterpiece and making yourself completely open to the work in question take some effort. It is, however, intensely rewarding.

A Woman Bathing in a Stream and The Anatomy Lesson of Dr Jan Deijman feature in Rembrandt – The Late Works which runs at the National Gallery in London from 15 October until 18 January 2015.

Maggi Hambling: Walls of Water opens at the National Gallery in London on 26 November and runs until 15 February 2015.

Rembrandt on BBC Arts

-

![]()

Hidden Rembrandt

Art Archeology: exploring what lies beneath the surface of a Rembrandt masterpiece using X-rays

-

![]()

Five Rembrandts

Artist and sculptor Maggi Hambling selects her five favourite paintings by the Dutch master

-

![]()

The Night Watch

What makes The Night Watch so iconic, and did Rembrandt's most famous painting end his career?

-

![]()

Art UK

Browse 112 paintings by Rembrandt in the Your Paintings collection

Art and Artists: Highlights

-

![]()

Ai Weiwei at the RA

The refugee artist with worldwide status comes to London's Royal Academy

-

![]()

BBC Four Goes Pop!

A week-long celebration of Pop Art across BBC Four, radio and online

-

![]()

Bernat Klein and Kwang Young Chun

Edinburgh’s Dovecot Gallery is hosting two major exhibitions as part of the 2015 Edinburgh Art Festival

-

![]()

Shooting stars: Lost photographs of Audrey Hepburn

An astounding photographic collection by 'Speedy George' Douglas

-

![]()

Meccano for grown-ups: Anthony Caro in Yorkshire

A sculptural mystery tour which takes in several of Britain’s finest galleries

-

![]()

The mysterious world of MC Escher

Just who was the man behind some of the most memorable artworks of the last century?

-

![]()

Crisis, conflict... and coffee

The extraordinary work of award-winning American photojournalist Steve McCurry

-

![]()

Barbara Hepworth: A landscape of her own

A major Tate retrospective of the British sculptor, and the dedicated museums in Yorkshire and Cornwall

Art and Artists

-

![]()

Homepage

The latest art and artist features, news stories, events and more from BBC Arts

-

![]()

A-Z of features

From Ackroyd and Blake to Warhol and Watt. Explore our Art and Artists features.

-

![]()

Video collection

From old Masters to modern art. Find clips of the important artists and their work