'Chaos is present everywhere': The mysterious world of MC Escher

By William Cook | 29 June 2015

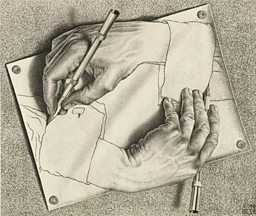

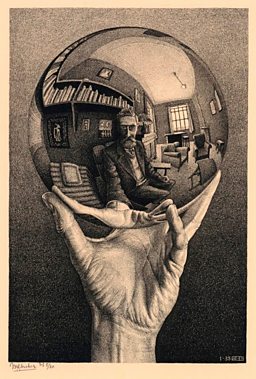

He created some of the most memorable artworks of the last century, yet the man who made them remains virtually unknown. Who on earth was MC Escher? What inspired his perplexing imagery? And why have we been deprived of an exhibition of his work for so long?

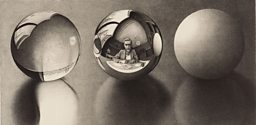

MC Escher’s otherworldly pictures are instantly recognisable. You’ll have seen them countless times, even if you don’t know his name. For over half a century his dreamscapes have adorned the walls of student bedsits. He’s revered by everyone from spaced-out hippies to sci-fi nerds, yet he’s never been taken terribly seriously by the art establishment.

When Mick Jagger wrote to him, asking if the Rolling Stones could use one of his pictures as an album cover, Escher turned him down. He’d never heard of the Stones

Remarkably, there’s only one Escher in a British collection. Incredibly, this fine show, at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, in Edinburgh, is the first major retrospective ever mounted in the UK. "Everyone knows the images but no one knows about him," says Patrick Elliott, the gallery’s chief curator.

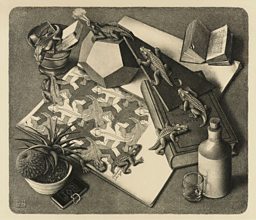

There are several reasons for this neglect. Escher was a printmaker, working mainly with woodcuts and lithographs. In grander galleries, printmaking has traditionally been (wrongly) regarded as a poor relation to painting.

Escher was a superb draughtsman, at a time when technical expertise became unfashionable. He was populist and timeless – trendy art critics preferred to praise the obscure and opaque. But though the cognoscenti ignored him, his fans adored him. Only now is the art world starting to catch up.

To be fair, one reason why Escher never became as famous as his artworks was because Escher wanted it that way. He liked to live a quiet life - he didn’t court publicity. He wasn’t interested in celebrity – his only concern was his work. When success started intruding on his time, he put up his prices to try and dampen demand. It had the opposite effect.

Escher was mystified by his cult status as a counter-cultural artist. He didn’t share the values of the beatniks who admired him. Like a lot of truly creative men, he enjoyed a conventional, bourgeois lifestyle.

When Mick Jagger wrote to him, asking if the Rolling Stones could use one of his pictures as an album cover, Escher turned him down. He’d never heard of the Stones. He’d never heard of Jagger. He objected to Jagger addressing him by his first name. One particularly revealing exhibit in this show is a Rolling Stone article in praise of Escher, from the artist’s archive. Escher has underlined the most pretentious passages, annotated with question marks.

Chaos is present everywhere, order remains an impossible idealMC Escher

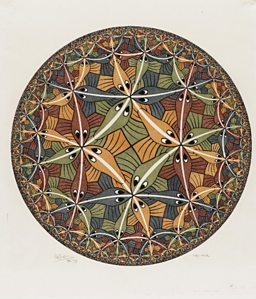

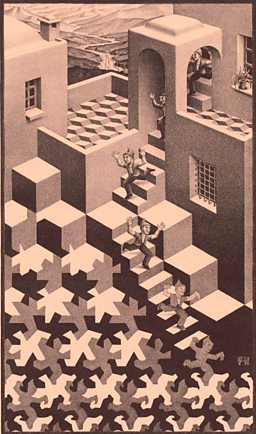

Maurits Cornelis Escher was born in the Netherlands in 1898. His father was a civil servant who collected Japanese art. Maurits didn’t shine at school, but he had a flair for drawing, influenced by his father’s Oriental art collection (he was also inspired by the Islamic art of the Alhambra in Granada).

He went to technical college to study architecture, but a perceptive teacher convinced him to switch to graphic design. Even so, his other teachers weren’t persuaded. They thought him too literary and philosophical to succeed.

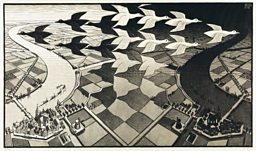

After college, Escher lived in Italy and then in Switzerland before returning to the Low Countries. In Italy he drew from life. Back home in the Benelux, he drew a world of his own, with its own reality. "Chaos is present everywhere," he reflected. "Order remains an impossible ideal."

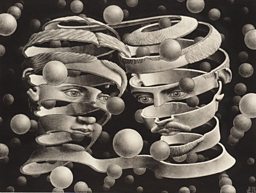

Escher married and raised a family, but as an artist he was reclusive. He developed his own style, free from any school or movement. He had more in common with medieval artists like Hieronymus Bosch than his surrealists contemporaries like Dali or Magritte.

Escher was fortunate that his parents were comfortably off, and sympathetic to his vocation. They supported him until his forties, when his art finally began to pay.

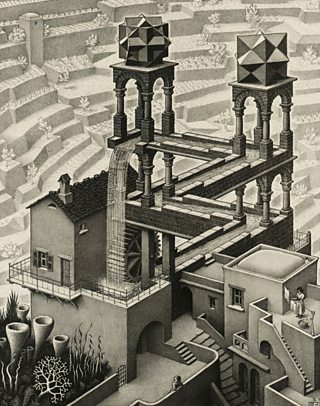

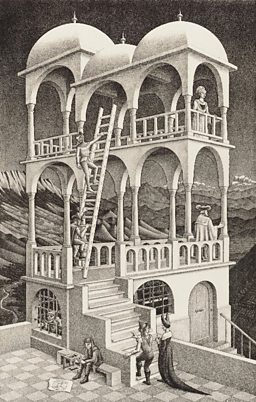

In 1954 Escher was acknowledged (in his native Netherlands, at least) with an exhibition at Amsterdam’s Stedelijk Museum. The eminent mathematician Sir Roger Penrose (now Professor of Mathematics at Oxford University, then a young student at Cambridge) was attending an academic conference in Amsterdam at the same time Penrose saw Escher’s show, and loved it.

"It was just so original and so precise," says Penrose. "He’s playing with ideas, but in a completely consistent way."

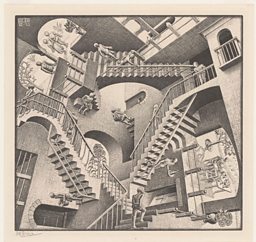

The two men became pen pals, sharing ideas of ‘impossible images’. Escher was thrilled to find that his fantasies had some mathematical basis. Penrose was thrilled to see his theories transformed into art. Escher’s friendship with Penrose inspired two of his greatest artworks – Ascending & Descending and Waterfall.

"Sometimes people compare his art with psychedelic art or surrealist art, but there’s something crucially different," says Penrose. Unlike the surrealists, Escher’s parallel universe has its own internal logic. Like the best science fiction – and mathematics - it’s a world that works.

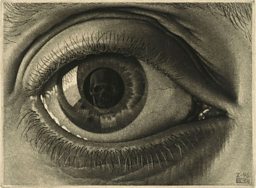

It’s surprising how many of the pictures in this retrospective are familiar from magazines and posters, but it’s a completely different experience seeing the real thing. You’re struck by Escher’s delicate touch, his extraordinary eye for detail. "It makes Taschen reproductions look like photocopies," says Elliott.

You return to those old reproductions with a new respect for his meticulous technique. But Escher’s artworks aren’t just exercises in artistic wizardry. He questions our perceptions of reality.

"Are you absolutely sure a floor can’t also be a ceiling?" he once asked, impishly. After you’ve seen this exhibition, a staircase or a waterfall will never look quite the same again.

The Amazing World of MC Escher is at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh until 27 September, and then at Dulwich Picture Gallery from 14 October until 17 January 2016. Escher is also the subject of a forthcoming Secret Knowledge documentary.

All images courtesy of the collection Gemeentemuseum Den Haag, The Hague, The Netherlands. © 2015 The M.C. Escher Company – Baarn, The Netherlands.

Related Links

Art and Artists: Highlights

-

![]()

Ai Weiwei at the RA

The refugee artist with worldwide status comes to London's Royal Academy

-

![]()

BBC Four Goes Pop!

A week-long celebration of Pop Art across BBC Four, radio and online

-

![]()

Bernat Klein and Kwang Young Chun

Edinburgh’s Dovecot Gallery is hosting two major exhibitions as part of the 2015 Edinburgh Art Festival

-

![]()

Shooting stars: Lost photographs of Audrey Hepburn

An astounding photographic collection by 'Speedy George' Douglas

-

![]()

Meccano for grown-ups: Anthony Caro in Yorkshire

A sculptural mystery tour which takes in several of Britain’s finest galleries

-

![]()

The mysterious world of MC Escher

Just who was the man behind some of the most memorable artworks of the last century?

-

![]()

Crisis, conflict... and coffee

The extraordinary work of award-winning American photojournalist Steve McCurry

-

![]()

Barbara Hepworth: A landscape of her own

A major Tate retrospective of the British sculptor, and the dedicated museums in Yorkshire and Cornwall

Art and Artists

-

![]()

Homepage

The latest art and artist features, news stories, events and more from BBC Arts

-

![]()

A-Z of features

From Ackroyd and Blake to Warhol and Watt. Explore our Art and Artists features.

-

![]()

Video collection

From old Masters to modern art. Find clips of the important artists and their work