Cold War in Full Swing - Louis Armstrong in the GDR

Kevin Le Gendre discovers how Louis Armstrong came to play jazz in communist East Germany during the Cold War, when previously a passion for the music could land you in prison.

Jazz and communist East Germany seem unlikely bedfellows. Yet in 1965 Louis Armstrong became the first American entertainer to play jazz there at the height of the Cold War. East Germans celebrated Armstrong, and his visit became a propaganda victory for East Germany, helping it to boost its reputation in the wake of its oppressive government building the Berlin Wall in 1961.

On his brief and only tour through East Germany Armstrong played to packed houses. His popularity surprised the authorities very much considering not one record of him was available before 1965 and your passion for the music could land you in prison.

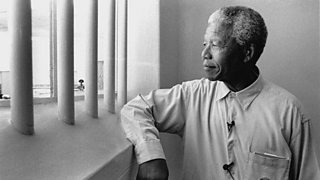

Kevin Le Gendre peeks through the former Iron Curtain to discover the dangers jazz lovers faced to pave the way for these legendary concerts to happen while tracing the tour. He speaks to jazz journalist Karlheinz Drechsel who first risked his career for jazz but then, amazingly, had the privilege to accompany Louis Armstrong on the tour and announce his concerts. He tells Kevin what it was like meeting Louis Armstrong and seeing beyond the smile and laughter that Louis Armstrong was famous for. Armstrong not only had to navigate political sensitivities on the Cold War front between east and west, but also on the home front in the US, when questioned about the Civil Rights Movement, which was at its peak.

The tour left a big impression on both sides. Armstrong was very taken by the enthusiastic welcome he received and East Germany, far from the authorities’ intentions, developed a Free Jazz scene that became an unexpected export hit.

Speakers include the journalists Karlheinz Drechsel, Siegfried Schmidt-Joos and Leslie Colitt; the jazz fan Volker Stiehler; the authors Ricky Riccardi and Stephan Schulz; pianist Ulrich Gumpert; and Roland Trisch, who worked at East Germany’s Artists Agency, which enabled Louis Armstrong’s tour. Archive material of the Selma to Montgomery march in Alabama on 7 March 1965 is courtesy of the Robert H Jackson Center.

Producer: Sabine Schereck

Last on

More episodes

Previous

Louis, Jazz in the GDR and Gems to Discover

A producer’s note

A few years ago, the journalist Siegfried Schmidt-Joos told me, he was working on a book about jazz in the GDR. It intrigued me. To me, as a West Berliner, the GDR was always that grey and grim place on the other side of the wall. The association with jazz seemed odd, but if there was jazz, it was certainly a white spot on the map that seemed worth exploring…

And along came Louis Armstrong, that is, his tour through the GDR in 1965, when I was researching the subject, followed by numerous other discoveries. These included not only basic facts such as the 60,000 people Armstrong was playing to, or the way fans could obtain tickets in a country that was against capitalism. Of course, some could be bought, but others were distributed by state-run organisations.

Ronald Trisch, who worked for the artist agency in the GDR that was responsible for arranging Armstrong concerts there, recalls: “This had been the only time at the Friedrichstadtpalast that six concerts, two performances per day on three days, that is six concerts with 3,000 seats were sold out, so 18,000 visitors.” That was in East Berlin. The old Friedrichstadtpalast where the concerts took place, doesn’t exist anymore. It stood right next to the Theatre am Schiffbauerdamm, better known as the Berliner Ensemble now. It was the theatre, where almost 40 years earlier ‘Die Moritat von Mackie Messer’ was first heard during the premier of ‘The Threepenny Opera’ in 1928. By 1965 this song had become an international hit called ‘Mack the Knife’ - thanks to Armstrong’s jazzed up version recorded in 1956.

The East German authorities were also stunned by Armstrong’s popularity because there weren’t many references to him in East German state-run newspapers up to 1965. It wasn’t until late January 1965 when the newspapers announced the East German Amiga label had recently produced pressings of two Louis Armstrong records, one called ‘Louis Armstrong’, the other ‘Louis Armstrong Oldtime Jazz’, with his recordings from the 1920s and 30s, that is with Armstrong’s Hot Five and Hot Seven.

Louis Armstrong’s concert tour in the GDR was a sensation but when I asked Schmidt-Joos what the West German press made of it, he hadn’t much to say: “It was no more than information in a news item.“

“Jazz is forbidden, so you can only place ads for dance music records.”

The reason for him to write a book about jazz in the GDR was his personal involvement. He had grown up there and championed jazz with a group of like-minded people by giving talks, writing about it and organising concerts. Upon hearing Gene Krupa’s drum solo in the song ‘Sing Sing Sing’ on the radio, when he was a teenager, he was keen to find out more. Then, when he tried to get hold of jazz records second hand through an advertisement in his local newspaper, he was told: “Jazz is forbidden, so you can only place ads for dance music records.” In German that’s ‘Tanzmusik’ and radio orchestras and other orchestras that played swing and the music of big bands were called Tanzmusikorchester. There were quite a few around in East Germany. Nevertheless, when tracing the authorities’ attitude towards jazz in the GDR from the 50s to the 70s, it oscillates between tolerating it and banning it, with a few steps towards accepting it along the way. It also depended on the local authorities in question: some were more lenient than others towards jazz. Of course, the East German secret police, the Stasi, also had their spies on the jazz scene, but they were cautious about denouncing fellow jazz musicians “as it would prevent them from having anybody to play jazz with,” explains jazz afficionado Detlef Ott.

Besides the professional orchestras, there were a lot of amateur bands. They enabled people to listen to the music, which was otherwise hard to get hold of. Very little jazz was played on the radio and records mainly had to be smuggled into the GDR. The country’s own Amiga label, if at all, mainly recorded the music performed by GDR bands.

The bands often played Dixieland, which was more acceptable in the GDR than the modern jazz which had emerged in the 50s. Schmidt-Joos’ best friend also had an amateur Dixieland band, Alfons Zschockelts Jazz Band Halle. They were of a high standard as they were even invited to perform in Moscow. I was thrilled when I came across a 10-CD-Box with jazz and swing from GDR produced between 1947 and 1962. It not only contained the Helmut Brandt-Combo, Schmidt-Joos refers to in the interview, but also a recording made by Zschockelt’s band, ‘That Da-Da Strain’, which has a very catchy tune. It was made in July 1957. Two months later, he and Schmidt-Joos left the GDR for good. The pressures of the Stasi and the tense atmosphere at their university in Halle, which increasingly required double talk, drove them to it. Leaving their families behind, they started a new life in West Germany.

Ironically, a few months before their escape, Zschockelt had received an invitation to perform in Dresden in October. It came from Karlheinz Drechsel. Like Schmidt-Joos, he had also established a group to promote jazz and became a renowned jazz journalist. He stayed in the country and repeatedly risked his life for his passion. In 2004, long after the collapse of the GDR, he was awarded an order of merit by the German government for his achievements in paving the way for jazz in the GDR.

He remembers the difficulties of getting hold of jazz records by different means: the black market; smuggling them across the border from the West; friends of friends who, in the middle of the night, would throw packages with records out of moving cars on the motorway en route from West Germany to Berlin. There was also the jazz lift, where American organisations covertly sent records behind the Iron Curtain.

And there were people, who knew exactly what it was like to be in this position. So, some of the records that landed on his desk came from Schmidt-Joos, who had settled in the West. In that way, Schmidt-Joos also supplied music to his brother, who was later involved in the concert series ‘Jazz in der Kammer’, which presented contemporary, cutting-edge East German jazz. It was set up in late 1965 in East Berlin in the wake of Armstrong’s tour and remained a staple on the East German jazz scene until the country’s dissolution in 1990.

“Armstrong was a door opener”

“Armstrong was a door opener,” Drechsel and Ronald Trisch agree. For Trisch it meant that it was easier to place concerts with East German jazz bands. He fondly remembers a lunch with Armstrong, who heartily enjoyed a dish of ‘Eisbein’, a pickled knuckle of pork. This traditional German dish became Armstrong’s favourite during the tour.

For Drechsel, Armstrong’s visit also meant treasured memories as the artist agency had asked him to introduce Armstrong’s concerts and accompany him on tour. He thus got to know him at close quarters. When Armstrong arrived at Schönefeld Airport in East Berlin on 21 March 1965, it was a cold and windy afternoon. Drechsel distinctly remembers Armstrong entering the hall, receiving his welcome, briefly talking to journalists, and making a beeline to the band The Jazz Optimists, who played his theme song ‘When It’s Sleepy Time Down South’, with which he opened his concerts. “And he said: ‘Pardon me, I have to sing. That's my song’,” Drechsel recalls, and Armstrong joined in. “Absolute silence. Louis’ voice was in the air.” The Jazz Optimists were, of course, chuffed. The sound recording of Armstrong’s arrival is a gem in itself. It was given to me – and, as it turned out, it was not in any public archive.

Armstrong’s generally cheerful disposition also shone through when, after the concerts in Leipzig, he and his band The All Stars needed to get back to Berlin quite quickly. All that was available was a freight plane – and Drechsel was with them: “No seats, nothing, only very simple seats and the plane was moving around a lot. It was very bad weather. The musicians and I were struggling with our stomachs. We had white faces. But Louis had a laughing face. He was happy.”

I mentioned that the Friedrichstadtpalast, in which Armstrong performed, doesn’t exist anymore, neither does the Hotel Berolina, in which he stayed when in Berlin. However, in Leipzig, the trade fair hall still stands. It’s a huge, grey, sober hall, now transformed into a shopping centre, as the trade fair has moved out of the city centre. The Hotel Deutschland in Leipzig also still stands, although operating under a new name and management. It’s also been heavily refurbished, so that the suite in which Armstrong stayed no longer exists. In March 1965, when Armstrong visited, the top-notch, newly-built hotel had just opened and Armstrong was their first VIP. Kathleen Tippner, a spokesperson at the hotel, dug out some archive material about Armstrong’s stay there. It included a promotional calendar with a photo of Armstrong in his suite.

“Who's the real ambassador?”

His status and ability to build bridges was also clear to his fellow countrymen. Armstrong had first played in African countries in 1956. Two years later, ‘The New Yorker’ published a cartoon by Mischa Richter showing eight middle-aged white men in suits at a conference table. Underneath the caption read: “This is a diplomatic mission of the utmost delicacy. The question is, who's the best man for it – John Foster Dulles or Satchmo?”

In 1960, Armstrong was sent on a US State Department Tour to Africa, playing in countries such as Ghana, Nigeria and the Congo. They were not just randomly chosen countries in Africa. They just had gained, or were about to gain, independence, and the war between the Cold War rivals, the East and the West, was also playing out there. Would these countries join the Eastern or the Western camp? The US wanted to show them through Armstrong that the West would be the better choice. Artists who were sent on such State Department tours, including Dizzy Gillespy and Dave Brubeck, became known as the Jazz Ambassadors. With a twinkle in his eye, Brubeck and his wife Iola turned the work of the Jazz Ambassadors into a musical called ‘The Real Ambassadors’. It featured Armstrong singing the lines: “I'm the real ambassador! / It is evident I was sent by government to take your place / All I do is play the blues and meet the people face to face / I'll explain and make it plain I represent the human race / And don't pretend no more! […] Who's the real ambassador? Certain facts we can ignore / In my humble way I'm the USA! / Though I represent the government / The government don't represent / Some policies I'm for!” This, of course, referred to the civil rights movement in the United States.

“‘Ok, you are allowed to sing two songs’. But that was the end.”

Bringing the focus back to East Germany, the general view is that after Armstrong’s tour the authorities were somewhat more favourable towards jazz, but only to a certain degree. In December 1965, the authorities decided to tighten the rein again regarding culture, including jazz. One jazz pioneer in East Germany was particularly badly affected by it: Ruth Hohmann. She was the first to gain a professional licence as a jazz singer before 1965, but in early 1966 she was basically silenced. Events she was booked for were cancelled at short notice and a TV programme she was meant to appear on allegedly received letters of complaint about her jazz music and her singing in English, which included standards like ‘Moonlight in Vermont’. On one occasion, she took a stand. She was contracted to sing three numbers on television, but then informed she could only sing one. She argued: “We had agreed, I would sing three songs. If you don’t fulfil the contract, there’s no need for me to do so either, and I am going home.” The programme makers didn’t expect such a response. “They bat the matter around for more than an hour and then said: ‘Ok, you are allowed to sing two songs’. But that was the end.” She fell on hard times, also because she wouldn’t budge. Early on in her career, she was offered the opportunity to sing East German ‘pop music’ – she declined. She had taught herself to sing jazz, copying what she heard on the radio. Her first official gig was with the Jazz Optimists Berlin in November 1961 at the House of German-Soviet Friendship. It might sound like an unusual venue for jazz, but she explains: “The arts centres that presented culture from Poland, Hungary and Czechoslovakia often had jazz concerts on their programme, so did the Russians”. It showed that not all Eastern Bloc countries were equally as hostile towards jazz as the GDR was. She, of course, also went to see Armstrong. What impressed her most was “the fun, the playful relationship the musicians had with one another on stage.”

After Walter Ulbricht had put an end to her career in early 1966, she was finally able to resume it, when Ulbricht was replaced as head of state by Erich Honecker in 1971. Since then, she has become a fixture on the East German jazz scene and also played with Ulrich Gumpert, for example. Although their musical styles are miles apart on the jazz spectrum – she mainly sings old-time jazz, while he engages in free jazz, it still worked, she says. Both managed to navigate the turbulences after the fall of wall and both still devote their lives to playing jazz music.

“There was the feeling you were special”

Regine Dobberschütz’s career as a singer began in the late 1970s when she was a teenager in the GDR. She moved between different styles such as soul, jazz and rock. “There was the feeling you were special,” she says of the people who loved jazz in the GDR. “You didn’t get into radio with jazz music. But I didn’t want to sing any GDR pop, which was offered to me.” Then the authorities also told her: “’You have to decide what kind of music you sing.’ In their way of thinking, there was always only one box you could be in.”

Dobberschütz had a relatively good life in the GDR, where she could pursue her career as a singer. Yet she missed the freedom to travel and see live performances by international stars. “All you could hear was canned music. I remember the first thing we did when we came to West Berlin was going to the Philharmonie to see Ella Fitzgerald.” That was in 1984. Her longing for freedom and to see the world made her apply for official permission to leave the country for good. It took three years before this was eventually granted. She believes her fame may well have contributed to the authorities’ decision to let her go without drawing attention to her case. In 1980 she had provided the singing voice for the actress Renate Krößner, who starred in the film “Solo Sunny”. It became a classic and even won a Silver Bear at the international film festival Berlinale in West Berlin.

Dobberschütz later moved to Frankfurt to shape up the Jazzkeller, a renowned venue for jazz music. She very much enjoyed running the place with her husband without having to worry about the Stasi and the artist agency, which controlled the industry in the GDR. The Jazzkeller was even frequented by Louis Armstrong in the 1950s. “He didn't come to play, he came for a session and even sold wine. He was always up for a joke and said, ‘Who would like a glass of wine?’ Easy. That is what I heard”, she recalls.

For those, who would like to find out more about jazz in the GDR and Louis Armstrong’s tour there, here are some books I can recommend. Due to the subject matter, they are mainly in German.

Further reading:

Stefan Schulz: “What a wonderful World – Als Louis Armstrong durch den Osten tourte”

Siegfried Schmidt-Joos: “Die Stasi swingt nicht mit”

Karlheinz Drechsel und Ulf Drechsel: “Zwischen den Strömungen – Mein Leben mit dem Jazz”

Rainer Bratfisch: “Freie Töne – Die Jazzszene in der DDR”

Ricky Riccardi: “What a Wonderful World – The Magic of Louis Armstrong’s Later Years”

Broadcasts

- Sun 14 Jul 2019 18:45BBC Radio 3

- Tue 17 Aug 2021 22:00BBC Radio 3

Featured in...

![]()

Arts

Creativity, performance, debate