Sir David Attenborough – World Music Collector

It’s a little known fact that, during the early part of his career, Attenborough recorded dozens of unique musical performances by the communities he encountered while making his groundbreaking Natural History programmes.

A new documentary on Radio 3 brings these early recordings to life and reveals a new side to the broadcaster – as a lover of world music…

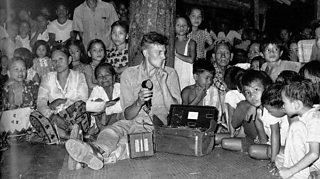

Attenborough recording a frog chorus in Sierra Leone in 1954 (Credit: David Attenborough)

Sir David shares the collection of musical field recordings he quietly amassed during his journeys across the globe, in a special edition of Radio 3’s Sunday Feature, and sheds light on the recordings that have remained locked away in the BBC archives for nearly six decades.

While I was theoretically looking for pythons, in the evenings I would record different types of music…

They feature an array of music: Gamelan orchestras in Bali; Fijian chants to attract turtles from the depths of the ocean; Aboriginal didgeridoo recitals; even the singing that encouraged adolescents to bungee jump off wooden scaffolding with only vines attached to their ankles during the land diving ceremonies in what was then the New Hebrides.

Each recording has a fascinating story to tell, as these examples taken from the documentary show:

Strange new technologies in Sierra Leone

Ever since the animal programmes of the early 1950s, when zookeeper George Cansdale used animals housed at London Zoo to illustrate basic zoological principles, Sir David harboured the desire to try something a little more ambitious outside the artificial confines of the television studio.

It was during his first expedition to Sierra Leone with the zoo’s curator of reptiles, Jack Lester – in search of, amongst other things, a Bald-headed Rock Crow – that he stumbled across his first opportunity to record a musical performance.

A village chief helping Attenborough and Lester to track down the bird offered to stage a performance by the village’s musicians and dancers. Among them was a player of a xylophone-like instrument called a balange.

Starting up his then state-of-the-art portable L2 reel-to-reel tape recorder (powered by ten torch batteries), Sir David recorded the musician’s performance. Aware that the villagers had never seen a recorder before, he wound the recording back manually and played back the sound on the equipment’s small speaker.

Dismissive of how quickly the machine had “learned” the piece of music, the balange player invited Sir David to record a second performance of far greater complexity. His beater sticks flurried across the wooden keys to create a dazzling piece full of scales and rapid notes.

Holding the speaker to his ear during playback, the musician’s eyes “rolled with pleasure” at the virtuosic music he’d been responsible for producing. He later expressed awe at the impressive pupillage of the tape recorder.

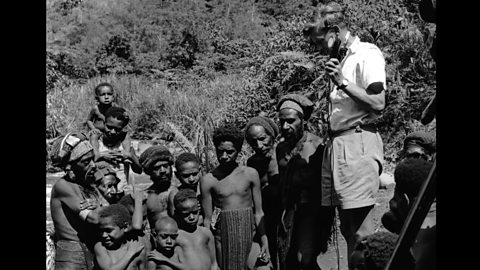

Prince Rudolph, King of Saxony and Count Raggi’s birds-of-paradise

On another occasion, Sir David was searching for birds-of-paradise native to New Guinea. He learned that the creatures had been hunted extensively in the Waghi valley, where their plumes were used in ceremonial headdresses and as a form of intertribal currency. He was told his best chances of capturing footage of these birds in the wild would be to travel to the valley of the Jimi River – a sparsely populated territory where travellers were liable to be ambushed and therefore required armed escort.

Around 100 Waghi porters assembled to carry all the supplies and gear that were needed to sustain the enterprise for several weeks. En route to the station in Aimoe, where Sir David and his team were to start their journey, the caravan of men provided him with an opportunity to record the songs they performed as they trekked.

A singing caravan of Waghi tribesmen

Attenborough explains the help he needed to transport equipment to find birds-of-paradise

Returning to the field

Sir David’s instinct to record the music of the people he encountered on his travels was driven by his intense curiosity around human artistic expression. He even nearly embarked on a postgraduate degree in Social Anthropology, although he had to put those plans on hold when he was put in charge of a new television channel, BBC Two. By the time he was able to return to full-time programme-making in 1973, technology had evolved – that L2 reel-to-reel tape recorder seemed obsolete.

The world in which these music expressions had originally found voice had also changed. Western society was increasingly impacting on ways of life that had hitherto been protected from its influence. So for Sir David, these recordings are highly evocative. “The point about sound,” he says, “is that it takes you straight back to when you recorded it”.

You can join Sir David on his adventures through world music on Christmas Day. Listen to David Attenborough – World Music Collector live on Radio 3 or listen online.