Why opera singers are the elite athletes of the concert hall

11 March 2016

In BBC Four series Pappano's Classical Voices, Sir Antonio Pappano explores the great roles and the greatest singers of the last 100 years through the prism of the main classical voice types - soprano, tenor, mezzo-soprano, baritone and bass. To tie in with the series, critic BRIAN MORTON writes about the extraordinary challenges of singing opera, and we present some choice performances from the BBC archive.

Take comfort if you've ever admitted to finding operatic voices 'unnatural', perhaps a little unearthly or inhuman. The experts probably agree with you.

In the same way, the appeal of opera isn't simply a reflection of taste but a fatal glamour to which you are either genetically programmed to succumb or else immune.

Singing opera is to ordinary vocal activity what triple-jumping and pole-vaulting are to ordinary exercise

Singing opera is to ordinary vocal activity what distance running, triple-jumping and pole-vaulting are to ordinary exercise, which means that singers and, almost as important, those who teach them are locked in the same kinds of relationship that obtain between elite athletes and charismatic coaches.

It's no more than coincidence but a neat coincidence that Antonio Pappano's series on classical voices should go to air at the same time as athletics coach Alberto Salazar defends his strange but, he insists, above-board training methods which have coaxed high-C performances out of runners like Galen Rupp and Mo Farah.

The operatic voice is unnatural, a cultural artefact rather than a given, or a gift. Some singers achieve greatness with little intervention. The majority require F1 technical support and fine-tuning.

It's also not a coincidence that the fathers of both Pappano and of Luciano Pavarotti should have been voice teachers. Singing at this level is a learned art, passed down with generations of physiological as well as psychological understanding.

Great voices from the BBC archive

The operatic voice has evolved in parallel with a repertoire that pushes it to ever higher levels not just of technical skill – those high-wire Queen of the Night acrobatics – but of emotional charge as well.

Being an operatic tenor means getting the girl but quite probably dying at the moment of success

As Pappano makes clear, being an operatic tenor means getting the girl but quite probably dying at the moment of success; being an operatic soprano means possibly getting the guy, but probably the wrong guy, and going mad in the process. There are few human activities that embrace insanity and mortality quite so comprehensively.

It's possible to be obsessed with the violin or the piano, but they can be put back in a case or the lid closed. The voice, Pappano insists, is unique in that we carry it around with us.

It carries our signature, not that of a Stradivari or a Bösendorfer; its wolf-notes are aspects of the singer, not of wood and wire, and there are no technicians, only doctors and psychiatrists, or voice-teachers, who combine both specialisms, to deal with wear and tear or catastrophic damage.

If the fatality associated with high voices seems an exaggeration, then consider what happened to the tenor Ludwig Schnorr von Carolsfeld who died 150 years ago this month after giving only (only!) four performances of Wagner's Tristan und Isolde opposite his wife Malvina, who had delayed the first performance by losing her voice. Regaining it made her a widow. It's a very operatic story.

Opera singers are stars again in a way they hadn't been since the 1950s. The global success of the Three Tenors and the odd but now unbreakable association of Nessun Dorma and association football has thrown the rigours of opera singing back into sharp cultural focus.

The connection between high-level singing and physical suffering seems hard to break

There has even been a revival of interest in the once-marginal art of male alto or counter-tenor singing, a kindly non-surgical alternative to that of the castrato.

A few recordings exist of the castrato Alessandro Moreschi, and somewhat gloomy listening they make, replete with sobs that would have embarrassed Johnny Ray but also because Moreschi was past his best before pioneering sound engineer condemned him to a kind of posterity.

The connection between high-level singing and physical suffering seems hard to break, not least when composers and librettists can think of no other reward for several hours in the upper octaves than poison or the knife.

Modern singers have benefited from more enlightened approaches and new technologies. X-ray, scanning and the oscilloscope have thrown fresh light on the physics and physiology of singing. Modern surgery has rescued many a career from nodes, polyps and inflammations.

Dame Joan Sutherland underwent gruelling facial surgery to repair sinuses, the antral cavities being just part of an inter-connected system of chambers and pipes that very precisely define the character of a voice.

Others haven't been so lucky. The Scottish soprano Isobel Buchanan recently returned to performance after being obliged to retire when an undiagnosed thyroid problem caused her voice to drop in pitch.

Great singers are, as Pappano makes clear, also great actors and great athletes. 'Temperament', a word loaded with ambiguous overtones, is of the essence, but it is clear from these passionate but detailed documentaries that 'temperament' is often merely a shorthand for a process of conditioning that sets singers apart from the rest of us not just in terms of creativity, but with the understanding that creativity, far from being amorphous, mysterious and God-given, is corporeal, and both tough and frail.

Pappano's Classical Voices is repeated on BBC Four on Sunday nights from 13 March 2016. A version of this article was originally published in June 2015.

Watch the show

-

![]()

Pappano's Classical Voices

The four-part series is on BBC Four from Sunday 13 March 2016.

Web exclusive clips

Tenor Ian Bostridge and Antonio Pappano perform and discuss the Elegy from Britten’s Serenade for tenor, horn and strings.

Tenor Jonas Kaufmann sings Die Rose, die Lilie, die Taube, die Sonne from Schumann’s Dichterliebe as you’ve never heard it sung before.

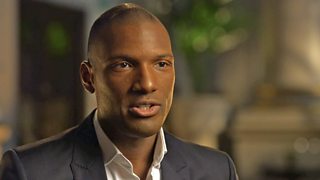

American singer Noah Stewart in rehearsal as Pinkerton in Madama Butterfly, and talking about his voice, his career, and being a tenor.

Antonio Pappano explores the physiology behind singing with Dr Ruth Epstein and Prof John Rubin, both of the Royal National Throat Nose and Ear Hospital, London.

The last person an opera singer sees before they go on stage is most likely their wig and make-up artist - as well as the stage crew as the singer makes his or her way to the stage. In this short film, members of the Royal Opera House backstage departments, past and present, remember their encounters with the great stars of opera.

Classical Voice season

-

![]()

Season homepage

Exploring the depth and power of classical singing across the BBC.

From BBC iWonder

-

![]()

Soprano to bass: Can you find your voice?

Conductor Tim Rhys-Evans explains the voice types.

-

![]()

Unplugged: Can your voice fill an opera house?

Vocal coach Mary King on the art of projection.

More on Antonio Pappano

-

![]()

Music Matters, 2014

Tom Service interviews Pappano for BBC Radio 3.

-

![]()

Opera Italia, 2010

A selection of clips from the BBC Four television series.

-

![]()

Desert Island Discs, 2004

The conductor picks his favourite music for BBC Radio 4.

More from BBC Arts

-

![]()

Picasso’s ex-factor

Who are the six women who shaped his life and work?

-

![]()

Quiz: Picasso or pixel?

Can you separate the AI fakes from genuine paintings by Pablo Picasso?

-

![]()

Frida: Fiery, fierce and passionate

The extraordinary life of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, in her own words

-

![]()

Proms 2023: The best bits

From Yuja Wang to Northern Soul, handpicked stand-out moments from this year's Proms