Shakespeare's players become the King's Men

By Alan H. Nelson, Record for Early English Drama editor

When Queen Elizabeth died on 24 March 1603, James the Sixth of Scotland acceded to the throne of England as James the First. But as James was in Edinburgh, he required more than a month to get to London.

By the time James got to London, plague was so rife that he postponed his coronation ceremony for almost a year. The same plague shut down the playhouses, leaving players without employment, at least in London.

-

![]()

Much ado near me

Hear more Shakespeare stories on BBC Radio London

-

![]()

Shakespeare Festival 2016

The BBC celebrates the genius of the bard

In the meantime the King's administration carried out its normal functions. On 18 May a warrant was issued authorising William Shakespeare and his companions to perform plays throughout the realm under royal patronage: the former Lord Chamberlain’s players were now the King’s Men.

Ten months later, on 15 March 1604, James finally had his coronation procession. As the festive day approached, the Lord Chamberlain issued red or scarlet cloth, to be made into livery garments, to more than a thousand royal servants, including twenty-eight players.

From the notebook recording the purchase and distribution of cloth we know the names of three playing companies, the King’s Men, the Queen’s Men, and the Prince’s Men, and we know the names of the nine or ten principal players of each company. The King’s Men were headed by William Shakespeare, the Queen’s Men by Christopher Beeston, and the Prince’s Men by Edward Alleyn. (The queen was Anne of Denmark. The prince was Henry, heir apparent until his tragic death in 1612.)

We don’t know exactly what William Shakespeare did with his four and a half yards of red cloth, or what role he played. The liveried players may have marched in procession, or may have lined the processional route. Two members of the Prince’s Men, Edward Alleyn, famous for his stentorian voice, and William Bird alias Bourne, proclaimed speeches at pageants which lined the processional route; maybe Shakespeare and his men did the same.

Some months later, from 9 to 26 August 1604, twelve fellows of the King’s Men were paid for their attendance upon the Spanish Ambassador at Somerset House. Here they performed not on stage, but literally as royal servants. With a likelihood approaching certainty, one of the twelve grooms of the chamber at Somerset House in August 1605, doubtless dressed in livery, was William Shakespeare.

Shakespeare’s youngest brother – and actor – is buried at Southwark, aged 27

Not long after one of Shakespeare’s career high-points - winning the patronage of the newly-crowned King James I - the death of his youngest brother Edmund at the young age of 27 will have been particularly poignant, as his brother was a player, too.

William Shakespeare was the eldest of four brothers, all of whom lived into adulthood, and all of whom outlived their father, who died in 1601. While John Shakespeare was alive at the birth of his grandson Hamnet, William’s child, he was also alive to witness Hamnet’s burial, on 11 August 1596. At the time of his death, therefore, John Shakespeare had four living sons, but not a single living grandson to perpetuate the family name. Nor would any grandson live to do so.

William’s next oldest brother was Gilbert, baptised October 13, 1566, buried 3 February 1612. Gilbert was evidently a haberdasher who dwelt in St. Bride’s parish in London. But he was buried in Stratford-upon-Avon, where the burial register describes him as adulescens, signifying “batchelor.” Richard, baptised 11 March 1574, about ten years younger than William, was buried 4 February 1613. Little is known about him except that he too probably died a bachelor.

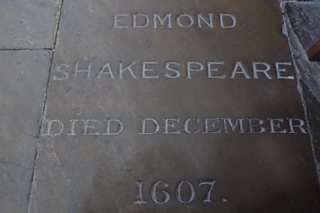

Edmund, William’s youngest brother and his junior by sixteen years, was baptised on 3 May 1580. In 1607 the register of St. Giles parish, Cripplegate, in London, records the burial of what is almost certainly Edmund’s own son, described as ‘base born’, or poor. Then Edmund’s own death is recorded in December 1607 at the parish of St. Saviour, Southwark. It records the burial of “Edmond Shakepspeare a player in the Church”. An entry in the monthly “bill” for the same parish records “Edmund Shakepspeare a player Buried in the Church with a forenoon knell of the great bell 20s [=twenty shillings]”.

Alan H. Nelson, Record for Early English Drama editor, writes: “At the time of his burial in 1607, Edmund Shakespeare was twenty-seven years old, known to two parishes as a player, the same profession as his elder brother. The parish of St. Saviour, Southwark, was the site of the Globe playhouse. As surviving lists of players do not include the name of Edmund Shakespeare, he was probably a minor actor, or an apprentice. Perhaps he led a bohemian life, as he buried a child classified as “base-born.” Edmund was evidently not wealthy enough to make a will. Nevertheless, he was buried “in the Church, ” a relatively rare dignity, with the tolling of “the great bell” at the high cost of twenty shillings, or one pound sterling. As his personal estate was probably not up to the cost, the obvious candidate to have paid the charge was his elder brother William, who was still connected to the Globe.”

Though Edmund Shakespeare was buried “in the Church,” the stone which now bears his name, located in the central aisle of what is now Southwark Cathedral, is a later creation.

Shakespeare on Tour

From the moment they were written through to the present day, Shakespeare’s plays have continued to enthral and inspire audiences. They’ve been performed in venues big and small – including inns, private houses and emerging provincial theatres.

BBC English Regions is building a digital picture which tracks some of the many iconic moments across the country as we follow the ‘explosion’ in the performance of The Bard’s plays, from his own lifetime to recent times.

Drawing on fascinating new research from Records of Early English Drama (REED), plus the British Library's extensive collection of playbills, as well as expertise from De Montfort University and the Arts and Humanities Research Council, Shakespeare on Tour is a unique timeline of iconic moments of those performances, starting with his own troupe of actors, to highlights from more recent times. Listen out for stories on Shakespeare’s legacy on your BBC Local Radio station from Monday 21 March, 2016.

You never know - you might find evidence of Shakespeare’s footsteps close to home…

Craig Henderson, BBC English Regions

The rise in status of London's playing companies

By Tanya Hagen, Bibliographer, REED

In 1604 as King James comes to power, one of the first things he does is to licence the company of actors formerly known as The Lord Chamberlain’s Men, to become The King’s Men.

The members of the company include Lawrence Fletcher, William Shakespeare, Richard Burbage, Augustine Philips, John Heminges, Henry Condell, William Sly, Robert Armyn and Richard Cowley.

They are authorised to perform all manner of entertainments, and 'to show and exercise publicly their

best commodity' at their present house, the Globe, and in any other place in the kingdom

The most interesting aspect of this document is less the biographical angle on the King’s Men company and its constituents - although the explicit link to the Globe theatre is certainly important - but that it marks a major transition in the system of theatrical patronage.

Up to this point, troupes had been patronised by wealthy members of the nobility; with James I’s ascension to the throne, however, theatrical patronage became an exclusively royal privilege. It is a mark of the Chamberlain’s Mens' importance and reputation that in this transition they became the protegés of the King himself.

Related Links

Shakespeare on Tour: Around London

-

![]()

Shakespeare's Players turned down at Kingston

The actors paid not to perform

-

![]()

The 1809 ticket price riots

The most famous riots in the history of theatre

-

![]()

The Lyceum Theatre performed Shakespeare in 1883

But which famous gothic writer worked here?

-

![]()

Charles Kean

The London theatre manager not lost for words

-

![]()

A historic performance of Coriolanus in London

The last performance of Coriolanus before the French Revolution

-

![]()

London's Female Romeo

Charlotte Cushman, who took Victorian London by storm

-

![]()

Curtains for London's Newington Theatre

The closure of London's first purpose built theatre south of the Thames

-

![]()

Shakespeare's Players turned away from Kingston

The actors paid not to perform

-

![]()

Shakespeare and the 'Night of Errors'

A series of unfortunate incidents at Gray Hall

Shakespeare on Tour: Around the country

-

![]()

Ipswich: a magnet for Shakespeare?

Why did Shakespeare's company visit Ipswich ten times?

-

![]()

Sarah Siddons visits Norwich

Putting the Theatre Royal, Norwich, on the map

-

![]()

Madame Tussaud's exhibiton in Nottingham

Including a model of William Shakespeare

-

![]()

Touring Kent to avoid the plague

In 1592, the plague forced touring theatre companies out of London