Ipswich: a magnet for Shakespeare's players

Shakespeare’s company visited Ipswich ten times — an unusually high number for that company and at a time when Shakespeare himself was an active member. But what was the attraction for the actors?

They first visited Ipswich in 1594-5, the year in which the troupe was re-formed as the Lord Chamberlain’s Men. As a young writer-actor, it seems most likely that Shakespeare would have been travelling with the troupe.

-

![]()

Much ado near me

Hear more Shakespeare stories on BBC Radio Suffolk

-

![]()

Shakespeare Festival 2016

The BBC celebrates the genius of the bard

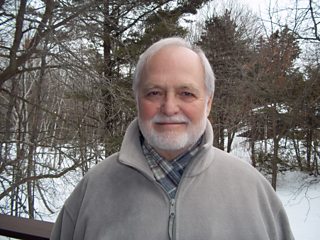

James Stokes, Suffolk editor from the Records of Early English Drama, writes: “Ipswich had been a port, perhaps England’s oldest, since 600 A.D., and the city had been a chartered borough from 1200 A.D. It was counted among the ten richest provincial cities during the period. An important trading centre since before the conquest, it was the hub for converging river traffic; it had become an important cloth town; engaged in continental trade.

The city paid Shakespeare’s company 40 shillings for its performance.

In addition, the city, as was Suffolk in general, was home to nationally important families of the first rank. For those reasons and others, East Anglia was the favored playing circuit among major troupes.”

In the same year, five other important troupes also visited Ipswich. The city paid Shakespeare’s company 40 shillings for its performance (four times as much as four of the other troupes, and twice as much the Queen’s Men, which was mainly a provincial touring company).

Clearly Shakespeare’s company was perceived locally as the most important of the six troupes. The records don’t record a date, a venue, or a play title for this first visit by Shakespeare and his colleagues, but the company would have had access to Shakespeare’s early history plays, the Taming of the Shrew, Titus Andronicus, and Richard III, among others—all of them huge crowd-pleasers.

The troupe next visited in 1603, now as the newly formed King’s Men or His Majesty’s Players. For that performance they received 26 shillings 8 pence. They were the only professional troupe to visit Ipswich that year, but Ipswich did pay considerable amounts to its own company of waits (singers and musicians). Given the extensive use of music in many of Shakespeare’s plays, perhaps the waits became part of the performance; other records confirm that the Ipswich waits acted as well as played music.

It is interesting to consider whether late spring in Ipswich would have lent itself more to comedy or tragedy.

Whether Shakespeare was present with his troupe in Ipswich in 1603, the records do not say. But this was their first visit representing the new king—a rather important moment. During the intervening eight years since the company’s first visit, the Bard had written his great history plays, Midsummer Night’s Dream, Merchant of Venice, other great comedies, Romeo and Juliet, Hamlet, and Julius Caesar. Why would the troupe have picked something other than one of those masterpieces, accessible in their repertoire, for the mayor, burgesses, and others in the Ipswich audience?

Shakespeare’s company performed again in Ipswich on 9 May 1609, by which time Shakespeare had written all the great tragedies, and two of the romances. It is interesting to consider whether late spring in Ipswich would have lent itself more to comedy or tragedy. The King’s Men visited again in 1617-18, as did the Queen’s (Anne’s) Players. The two troupes were each paid one pound, six shillings, eight pence, an amount that appears to indicate both monetary inflation and the growing importance of royal troupes throughout the kingdom. Although Shakespeare had retired in 1613, the company still had access to the complete canon of his plays.

Why did Ipswich become less welcoming to acting companies?

By James Stokes, Suffolk editor from the Records of Early English Drama

The worthies of the town gave the troupe what the city called a gratuity, essentially a payment to go away.

During the reign of Elizabeth I, Ipswich was a magnet for the most important national troupes. During her long reign, between four and seven of those troupes visited annually. In the reigns of James I and Charles I, the number fell to between two and three troupes each year.

Two striking features occur in the records. First, the Queen’s players (the royal troupe committed to provincial performance) visited far more often than those of any other patron. Second, during the reigns of James and Charles, most troupes fell away. Only the various royal troupes (Queen’s, Prince’s, Princess, King’s, Children of the Revels, and Lady Elizabeth) visited regularly. The Queen’s Men certainly would have had access to Shakespeare’s plays as their performance texts.

The final four appearances of The King’s Players in Ipswich all occurred during the reign of Charles I, but only one of the four resulted in a performance. In 1633-4, the troupe again received the same amount (one pound, six shillings, eight pence) for its play.

But in 1634-5, on 2 May 1637, and on 20 February 1638, each time when they arrived, the city paid the players not to perform; but in consideration of their royal patron, the worthies of the town gave the troupe what the city called a gratuity, essentially a payment to go away.

Whether the city feared the spread of illness, or local puritans objected, or some other reason was preferred, one cannot say, but three refusals in four years seems a significant pattern.

The company’s appearance in 1638 marks the melancholy end of sponsored professional drama in Ipswich until the Restoration.

Shakespeare on Tour

From the moment they were written through to the present day, Shakespeare’s plays have continued to enthral and inspire audiences. They’ve been performed in venues big and small – including inns, private houses and emerging provincial theatres.

BBC English Regions is building a digital picture which tracks some of the many iconic moments across the country as we follow the ‘explosion’ in the performance of The Bard’s plays, from his own lifetime to recent times.

Drawing on fascinating new research from Records of Early English Drama (REED), plus the British Library's extensive collection of playbills, as well as expertise from De Montfort University and the Arts and Humanities Research Council, Shakespeare on Tour is a unique timeline of iconic moments of those performances, starting with his own troupe of actors, to highlights from more recent times. Listen out for stories on Shakespeare’s legacy on your BBC Local Radio station from Monday 21 March, 2016.

You never know - you might find evidence of Shakespeare’s footsteps close to home…

Craig Henderson, BBC English Regions

Where did Shakespeare’s Actors Perform in Ipswich?

Payments in the Ipswich civic records don’t usually say where performances occurred, but between 1564 and 1572, some records indicate that the plays were staged in the Moot Hall (also called the Guild Hall or The Hall), which was located on The Cornhill.

The Hall was ‘converted from, or erected immediately to the north of, the redundant medieval church of St. Mildred.’ Originally the Corpus Christi Guild Hall, it became the principal building of city government. The records mention no venues after 1571, but in 1614, the city ordered that no plays be staged in The Moot Hall, indicating that officials were putting an end to a common practice. Shakespeare’s troupe likely performed in the Ipswich Moot Hall in 1594-5, 1603, and 1609, during the peak of Shakespeare’s time with The King’s Men. The Moot Hall was removed in the nineteenth century, replaced at that time by a town hall.

Related Links

Shakespeare on Tour: Around Suffolk

-

![]()

Aldeburgh’s Moot Hall – where Shakespeare's troupe performed

Venue still standing in Suffolk

-

![]()

Dunwich - a destination point for Shakespeare's players

What drew Shakespeare and his players to Dunwich?

-

![]()

Fledgeling Ipswich Theatre shows a passion for Shakespeare

Touring players from Norwich visit Ipswich

-

![]()

Shakespeare's Men perform in Sudbury

Before the Puritans seem to take hold

Shakespeare on Tour: Around the country

-

![]()

Ira Aldridge

Ira Aldridge - the first black Shakespearean actor

-

![]()

Blossoming at the Rose Theatre

Shakespeare, budding playwright and actor, at the Rose Theatre from the spring of 1592

-

![]()

Will Kemp dance finished in Norwich

Why did Will Kemp, Shakespeare's former clown, dance from London to Norwich?

-

![]()

London's Female Romeo

Charlotte Cushman, the American actress who took Victorian London by storm