Jackson Pollock's forgotten bleak masterpieces: The 30-year wait for 'black pourings' exhibition

By William Cook | 30 June 2015

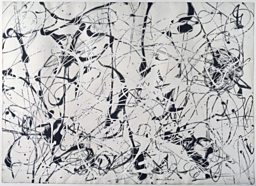

If you’re anything like me, you probably know Jackson Pollock from his multi-coloured ‘action paintings’ – those extraordinary, explosive pictures that transformed our idea of modern art. But there’s another side to Pollock that normally remains unseen.

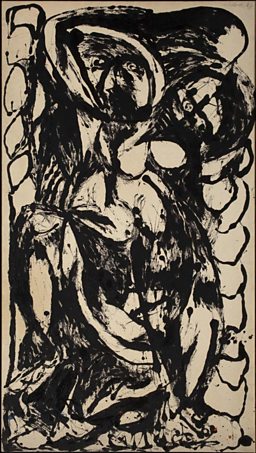

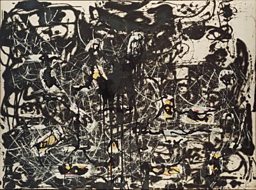

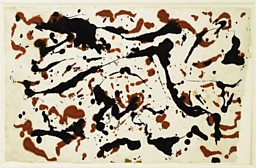

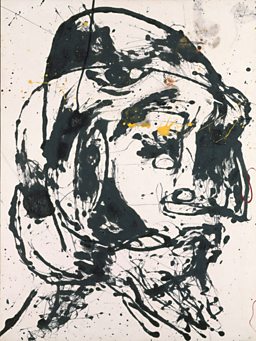

In 1951 he abandoned colour, and painted a series of disturbing pictures in black paint on bare canvas. These ‘black pourings’ from the basis of this remarkable exhibition, at Tate Liverpool.

For the first time ever it is a peek inside an unknown part of Jackson Pollock— Gavin Delahunty

"What this show really gives the audience – for the first time ever – is a peek inside an unknown part of Jackson Pollock," says the show’s curator, Gavin Delahunty. It makes us see him in a completely different way.

"People will expect to see the splashes, people will expect to see the abstraction," says Francesco Manacorda, Artistic Director of Tate Liverpool.

Instead, what we see here is an artist searching for a middle ground between abstraction and figuration. "It was the cusp of something new."

By 1950 Pollock had become the darling of the American art scene. "Is he the greatest living painter in the United States?" asked Life magazine. His drip paintings divided audiences, but everyone had an opinion about them.

Love him or hate him, he was the most talked about artist in America. Still the right side of 40, his future as a successful artist seemed assured.

However Pollock didn’t want to just keeping churning out endless variations on a winning formula. His lurid drip paintings had been revolutionary, but now he needed to change direction. He was sick of being pigeonholed - he wanted to try something new.

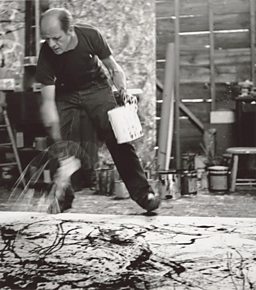

At the Betty Parsons Gallery in New York, he unveiled a range of arresting artworks – a furious collision between paint and canvas, in startling monochrome.

‘Good show, Jackson – but could you do it in colour?’— Charles Egan

"He was making monochromatic paintings before any other artist in America," says Delahunty.

Other New York artists loved these paintings (Robert Rauschenberg was an avid fan) but commercially, the exhibition was a failure. "Good show, Jackson – but could you do it in colour?" asked a rival gallerist, Charles Egan.

Parsons didn’t sell a single painting (she eventually sold one, after the show closed, at half price, to a friend). Pollock was furious, but it wasn’t Parsons’ fault.

It was hardly surprising that the art establishment – and the public - didn’t ‘get’ his latest paintings. It was more surprising that they’d gotten the ones he’d done before.

"They were confused," says Delahunty. "They couldn’t keep up." For Pollock’s audience, it was simply too much, too soon.

Pollock descended into a spiral of depression and drinking. "NYC is brutal," he observed. In 1956, he crashed his car into a tree at 80mph, killing himself and a female passenger (and badly injuring another). He’d barely painted anything for several years. He was 44 years old.

Pollock’s violent death ensured his lasting fame, but in most surveys his black paintings are conveniently forgotten, an awkward distraction from his earlier, more attractive work.

When I’m in my painting I’m not aware of what I’m doing, the painting has a life of its own— Jackson Pollock

"They fell between the cracks in art history – they’ve been almost lost," says Delahunty.

His show aims to recast these pictures as a key stage in Pollock’s career - as important, in their own way, as the colourful paintings that preceded them. Does he succeed? Well, yes and no.

On the one hand, you can see why Pollock’s black paintings didn’t sell. When Pollock painted in colour, his pictures were exuberant and life-affirming. With those lurid hues stripped away, they’re terribly bleak.

But just because you wouldn’t hang one in your living room, that doesn’t make them bad, or inconsequential. Hung together, in a gallery, they’re astonishing – a riveting portrayal of anger and despair.

"When I’m in my painting I’m not aware of what I’m doing," said Pollock. "The painting has a life of its own."

In his final paintings, colour returned to Pollock’s palette, like sunshine after a storm. These paintings are still alarming, but their old joie de vivre has returned.

One picture, in particular, offers a tantalizing vision of what might have been, if he’d conquered his demons – and his alcoholism – and found the strength to carry on.

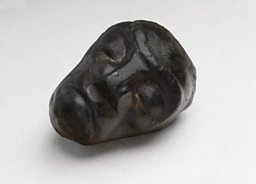

Portrait and a Dream combines an abstract and a human face. Having broken the boundaries of abstraction, was Pollock about to make a dramatic return to figuration?

Sadly, it was the last major painting he ever made. "The real tragedy is that, in my opinion, the black paintings signalled huge potential," says Delahunty. "We’ll never know what the man was going to do next."

So how significant was Pollock? And is he still significant today?

"There’s art before Jackson Pollock and there’s art after Jackson Pollock," says Delahunty. "It’s a rare moment in an artform - when someone comes along and they do something so radical that it fundamentally changes the course of that discipline, and Pollock was one of those artists."

And yet, in a way, he was no different from the Old Masters. "Painting is a state of being," said Pollock. "Painting is self-discovery. Every good artist paints what he is."

Jackson Pollock: Blind Spots runs at Tate Liverpool until 18 October and then at the Dallas Museum of Art from 15 November to 29 March 2016.

Images courtesy © The Pollock-Krasner Foundation ARS, NY and DACS, London 2015, Munson Williams Proctor Arts Institute/Art Resource, NY/Scala, Florence and Collection of the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth.

Related Link

Art and Artists: Highlights

-

![]()

Ai Weiwei at the RA

The refugee artist with worldwide status comes to London's Royal Academy

-

![]()

BBC Four Goes Pop!

A week-long celebration of Pop Art across BBC Four, radio and online

-

![]()

Bernat Klein and Kwang Young Chun

Edinburgh’s Dovecot Gallery is hosting two major exhibitions as part of the 2015 Edinburgh Art Festival

-

![]()

Shooting stars: Lost photographs of Audrey Hepburn

An astounding photographic collection by 'Speedy George' Douglas

-

![]()

Meccano for grown-ups: Anthony Caro in Yorkshire

A sculptural mystery tour which takes in several of Britain’s finest galleries

-

![]()

The mysterious world of MC Escher

Just who was the man behind some of the most memorable artworks of the last century?

-

![]()

Crisis, conflict... and coffee

The extraordinary work of award-winning American photojournalist Steve McCurry

-

![]()

Barbara Hepworth: A landscape of her own

A major Tate retrospective of the British sculptor, and the dedicated museums in Yorkshire and Cornwall

Art and Artists

-

![]()

Homepage

The latest art and artist features, news stories, events and more from BBC Arts

-

![]()

A-Z of features

From Ackroyd and Blake to Warhol and Watt. Explore our Art and Artists features.

-

![]()

Video collection

From old Masters to modern art. Find clips of the important artists and their work