Rediscovering Rembrandt: How the British rescued the master

4 July 2018

The revival of the once neglected Dutch artist Rembrandt van Rijn started in Great Britain, rather than his native Netherlands. As Edinburgh's Scottish National Gallery launches a major new exhibition WILLIAM COOK takes a tour of Rembrandt's roots in the Netherlands.

When Rembrandt van Rijn died, aged 63, lonely, bankrupt and neglected, there was little sign that he’d become such a central figure in the history of European art. His early fame had faded. His work no longer commanded high prices. Unable to pay his bills, he’d been evicted from his home and studio.

The nation where this revival started wasn’t his native Netherlands but Great Britain.

Yet today he’s universally revered. What happened? Well, since his death, in 1669, his reputation has grown and grown, and the nation where this revival started wasn’t his native Netherlands but Great Britain.

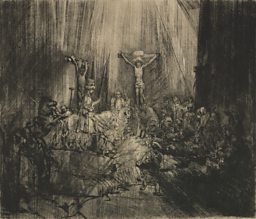

Rembrandt – Britain’s Discovery of The Master at the Scottish National Gallery tells the story of this renaissance. It begins with one of his acute self-portraits – his first work to leave the Netherlands when it was given to Charles I in 1633. It ends with gutsy works by Frank Auerbach and Leon Kossoff, two of the many British artists he’s inspired.

What drove this reappraisal? As usual, a big factor was money. Rembrandt’s career coincided with Holland’s Golden Age, an era of commercial prowess. Yet in the 18th Century Dutch fortunes dwindled while the British economy took off. Now Dutch paintings were cheap and British toffs had cash to burn. Built by Robert Adam, their new mansions had lots of wall space. A Rembrandt above the fireplace was a sign of wealth and taste.

There was a bit more to it than that, of course. If Rembrandt had been just a fad, his appeal would have worn off pretty swiftly. It was his revolutionary vision which ensured his legend would last. Incredibly for an artist who died during the reign of Charles II, Rembrandt didn’t anticipate the mannerism of the 1700s so much as the romanticism of the 1800s. It was 19th Century artists like Turner and Constable who really took him to their hearts.

It was Rembrandt's revolutionary vision which ensured his legend would last.

Where did this vision stem from? Well, Rembrandt was a genius, and genius is unique but it needs the right conditions in which to flourish. To understand the world he painted you have to travel to the land he lived in. In Holland, Rembrandt van Rijn is still very much alive.

The best place to begin your Rembrandt odyssey is in Leiden, where he was born in 1606, the third son of a local miller. Luckily for Rembrandt, his family had enough money to give him a good education at the local Latin School, but as they weren’t gentry they were perfectly happy for him to become a painter – a practical trade back then, rather than an idealistic calling.

Rembrandt was also lucky to be born in Leiden at the start of the 17th Century. The city had just emerged from a fierce war against the Spanish, in which it was brutally besieged. Located at the mouth of the Rhine, it now became a boom town, whose merchant class had the wealth and aspirations to support a thriving art scene. Rembrandt was apprenticed to a local artist, Jacob van Swanenburgh (like the Latin School, his studio is still here).

Leiden wasn’t just a commercial centre – it was an intellectual centre too. In 1575 it had become the seat of the first university in the Netherlands, which Rembrandt attended briefly. After learning his trade from van Swanenburgh, he shared a studio in Leiden with another up and coming artist, Jan Lievens. Art rarely thrives in isolation. They drove each other on.

There are no Rembrandts to see in Leiden right now (the city’s Lakenhal art gallery is closed for restoration) but The Hague and its palatial Maruitshuis is a short train ride away. Here you can see The Anatomy Lesson, the painting that made Rembrandt’s name. The other pictures that surround it, by other artists, show why it was so arresting. These other pictures are stiff and stilted. Rembrandt’s Anatomy Lesson is like a scene from a film.

In 1631 Rembrandt moved to Amsterdam, which had become the wealthiest city in the world, and at Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum you can see the painting that secured his fame. Like The Anatomy Lesson, The Night Watch wasn’t an unusual subject, but Rembrandt’s treatment of it was dynamic. Instead of a static group portrait, he produced a picture full of drama.

However the most remarkable thing about Rembrandt is his overwhelming empathy. He paints every human blemish, but his psychological insight is matched by his compassion. His portraits of his wife Saskia and his son Titus are full of sympathy, and that’s what makes them sing.

The endpoint of your pilgrimage should be the Rembrandthuis, also in Amsterdam. Rembrandt bought this grand townhouse in 1639 for 13,000 guilders – a huge sum in an age when a skilled workman only earned a few hundred guilders a year. He had to take out a mortgage, and although he subsequently earned enough money to pay it off, he spent it on other things. He built up a superb art collection, and bought all sorts of expensive curios – some as props for his paintings, others just for show.

When Rembrandt was making decent money this wasn’t such a problem, but in 1642 Saskia died, aged just 29. Their son Titus was still a baby. Plunged into a deep depression, his art became darker and more introspective. This period produced some of his finest work, but financially it was a disaster. Other artists loved it, but his wealthy patrons went elsewhere.

Rembrandt’s problems were compounded by his messy love life. He hired a nanny called Geertje Dircx to care for Titus. They became lovers but then Rembrandt left her for his housekeeper, a younger woman called Hendrickje Stoffels.

Geertje sued for breach of promise, Rembrandt counter sued. Geertje said he’d vowed to marry her, Rembrandt said she’d taken Saskia’s jewellery. Geertje said he’d given it to her. Eventually, he had Geertje committed to a ‘house of correction’ (somewhere between a prison, a workhouse and an insane asylum) where she languished for many years.

Rembrandt loved Hendrickje – she inspired some of his greatest paintings – but he never married her. Saskia had been a wealthy woman and she’d left Rembrandt a lot of money, but under the terms of her will he knew he’d lose this money if he ever remarried. When Hendrickje bore his daughter, she was called a whore and refused communion. As an artist, Rembrandt was famed for his sensitivity. As a man, he could be cruel.

Rembrandt went bankrupt in 1656 and was forced to sell this house and all its contents. For Rembrandt this was a catastrophe, but for the Rembrandthuis it’s been a blessing. The auditors compiled a comprehensive inventory of his assets, and the curators have used this inventory to reassemble the interior. Every room has been meticulously recreated. It’s like stepping into one of his paintings. It’s like stepping back in time.

The last decade of Rembrandt’s life was a sombre epilogue. He moved into a rented room in a poorer part of town. Hendrickje and Titus both predeceased him but he never stopped painting, and his last paintings are among his best. Go to Edinburgh this summer to see how Britain kept his genius alive. And then travel on to Holland, to see where it evolved.

Rembrandt – Britain’s Discovery of the Master is at the Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh from 7 July - 4 November 2018.

More on Rembrandt

-

![]()

Late masterpieces

Simon Schama explains the style and concept of Rembrandt's later work.

-

![]()

Art archaeology

X-rays reveals a hidden portrait beneath a painting by the Dutch master.

-

![]()

Rembrandt five

Artist Maggi Hambling CBE chooses her favourite works by Rembrandt.

Useful links

Current exhibitions

-

![]()

Streetwise art

How Keith Haring made New York City his canvas.

-

![]()

London calling

How the capital inspired Vincent van Gogh.

-

![]()

The original emoji

Why The Scream is still an icon for today.

-

![]()

Da Vinci decoded

See the Renaissance master's drawings in twelve UK cities.

More from BBC Arts

-

![]()

Picasso’s ex-factor

Who are the six women who shaped his life and work?

-

![]()

Quiz: Picasso or pixel?

Can you separate the AI fakes from genuine paintings by Pablo Picasso?

-

![]()

Frida: Fiery, fierce and passionate

The extraordinary life of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, in her own words

-

![]()

Proms 2023: The best bits

From Yuja Wang to Northern Soul, handpicked stand-out moments from this year's Proms