Life of the artist: David Hockney in conversation with Hans Ulrich Obrist

14 May 2015

Hans Ulrich Obrist has recorded more than 2000 hours of interviews with some of the world’s most important cultural figures. He has chosen 19 of these conversations for his new collection Lives of the Artists, Lives of the Architects. As David Hockney’s new exhibition Painting and Photography opens in London, in this excerpt from Obrist's book the artist talks about painting, poetry and his love of cigarettes.

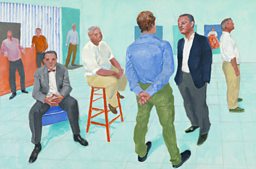

Hans Ulrich Obrist: You’ve done a lot of portraits of people in your entourage and friends and wider family, but you were never like Warhol, who did commissions of the rich and famous. Why was this was the case? Was it a conscious decision?

David Hockney: Yes, it was a decision. I deliberately didn’t want to do any commissioned portraits, because it’s not a problem I want to spend time on. Meaning, if you don’t know someone very well, how do you know if you’ve got a likeness? Andy’s portraits were done as a means of keeping his magazine [Interview ] going; it didn’t make any money, so he basically maintained it by painting German industrialists’ wives. Around the same time he was doing those, he did a portrait of me...

What was your relationship with Warhol like? Friendly?

Yes, we got on. I first met him in 1963. When he did the portrait, I did a drawing of him. My friend Henry Geldzahler [curator at Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York] didn’t like the portrait Andy had done, so he said to him, ‘Well, you’ve left something out, Andy’, and Andy was like, ‘No, what?’ And Henry replied, ‘You’ve left the art out!’ And Andy just said, ‘Oh well, I’ll do another’, which Henry liked.

There are quite a lot of references to [American poet] Wallace Stevens in your work ... so I was wondering about his work and its links to nature and in turn the links to your work...

I illustrated a poem of his called ‘The Man with the Blue Guitar’ about thirty years ago. It’s a terrific poem. Wallace Stevens is fascinating. Do you know he used to buy paintings in Paris through an agent without looking at them? Not by very good artists, but it was an odd way to get pictures, to trust someone like that.

You have always had a strong link to poetry.

I’ve done a lot of paintings over the years that were inspired by poetry. I haven’t for quite a while, but I still read poetry. There are certain things that I am not that acquainted with – one of them being lyrics of pop songs – so a lot of contemporary poetry I have some difficulty with because I don’t know all the allusions. Pop music, after a certain date, I know nothing about, nor care much about.

But certainly in the past, poetry played a big role in your work, notably with your piece We Two Boys Together Clinging [1961 ], which was named after the Walt Whitman poem . . .

Yes, Walt Whitman. I always loved the poem ‘I Saw in Louisiana a Live- Oak Growing’. It’s a bit like the Wallace Stevens line ‘I placed a jar in Tennessee . . .’ I’ve always known that the poet knows more . . .

Why do you say that?

Very early on I came across a poem called ‘Delight in Disorder’ and I thought, ‘I love that idea.’ It’s by Robert Herrick, the last lines are: ‘A careless shoe- string, in whose tie / I see a wild civility: / Do more bewitch me, than when art / Is too precise in every part.’ I read that when I was about ten years old and I thought, ‘Poets know more . . .’ Delight in disorder is something I think I have. It means you have a higher sense of order, actually. I’m a bit of a slob, I’m not that tidy, and I used to say it’s because I have a higher sense of order and I can see order where others can’t. And that was my excuse for being a slob.

And what about your link to Walt Whitman? I’m thinking specifically about your incredible 1961 print Myself and My Heroes, which features yourself, Walt Whitman and Mahatma Gandhi . . .

I admired Whitman when I was younger, but I also saw that he had serious flaws. He was certainly an interesting man but he was not quite the saint I thought at one time. He didn’t always take into account others’ fragility. When I first went to America I thought every schoolboy would be able to quote Walt Whitman, but most had never heard of him. I should have known! It was very American writing, it felt free, it seemed to me to be very fresh; I read the whole of Leaves of Grass, and it’s a vast thing. And then you realize the Americans have always been a little bit dubious because of their gayness; ‘for the dear love of comrades’, as Walt Whitman would say. He was one of the first great American literary figures who were taken seriously in England. They realized how good it was. It’s full of images, his poetry.

I always thought there should be a book of your writings, almost like a manifesto.

Well, I defend myself, that’s all I do.

Don’t you write every day?

No, I write when I get annoyed! Like when I get fed up with the anti- smoking campaigns. I think that writing ‘Smoking Kills’ on a packet of cigarettes is just part of the ‘uglification’ of Europe. You know what? Life’s a killer! So what? We don’t need to plaster it on everything, everywhere. I would certainly protest against the ‘demonization’ of smoking, which I think has been terrible. I’ve smoked for fifty- two years and, frankly, I’m fine. And I don’t intend to stop. Actually, I think I’d find it incredibly difficult to work without it, to be honest. It keeps you calm; and I’ve pointed out what will happen in the future if you think you can get rid of it... It’s exactly what’s happening in California right now: about forty per cent of the adverts on television in California are for prescription drugs. That is what will replace tobacco. The pharmaceutical industry will make the tobacco industry seem like Sunday- school teachers with what they’ll do to us. I remember seeing the death of Kennedy on television and the newsreaders were all smoking. It was a different world! I really loved New York when you could smoke anything, anywhere.

You should really bring together all your writings and publish a book.

Anything I write these days tends to be about one of my three keen interests: photography, perspective or smoking!

On the subject of books, I wanted to ask you about the beautiful illustrations you did based on things like Grimm’s Fairy Tales.

That was in 1968. I remember arguing with Francis Bacon about the word ‘illustration’. He’d use the word ‘illustrator’ as a put- down, as in ‘How’s your illustrating friend Mr Kitaj?’ [R. B. Kitaj, American painter] I knew Bacon a little bit, not much, but you could have a great argument with him. I’d tell him that some of the best artists were illustrators: Rembrandt, Bible stories, Hogarth...

And what did Bacon say?

We’d argue just for the sake of it! I pointed out to him once that I knew a painting in California of some tulips in a vase that was as profound as anything he’d done. It was by Cézanne and it was in the Norton Simon Museum. I was just trying to tell him that it wasn’t the subject matter that made images profound but the way they were treated. There was a period in the mid 70s when Bacon and I both lived in Paris and we’d see each other. Gregory used to go drinking with him...

It’s intriguing to think that, coming from the world of painting, how immersed you’ve been in all these other worlds: theatre, opera, illustration, art history...

As I said, I’m interested in images; I think that’s the thread always... I’ve always been interested in physics as well. Ultimately, the moment rules.

What do you mean by that?

The moment rules: for instance, I was painting these pictures of the countryside, but the moment the hawthorn blossom went, I stopped. We only had it for four days: after that the rain came and took it all away, so the moment has to rule, especially if you’re involved with nature because, after all, I’m living in Yorkshire, a place, unlike California, which changes throughout the year. Remember, for twenty-five years I didn’t see springs and summers in California, it was always the same weather.

So being here is the reintroduction of the seasons into your life.

Yes, that’s one aspect. Let’s go out for a drive so I can show you what I’m talking about.

Lives of Artists, Lives of Architects by Hans Ulrich Obrist, is available now, published by Allen Lane.

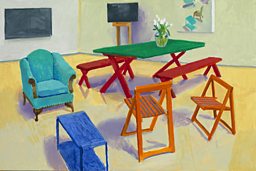

David Hockney, Painting and Photography is at Annely Juda Fine Art, London, from 15 May – 27 June 2015.

The interview project

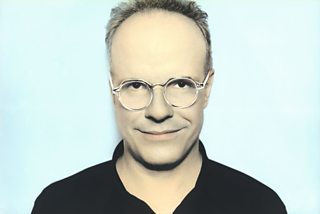

Hans Ulrich Obrist was just 17 years old when he began his interview project. His first conversation, in his native Switzerland, was with the artists Peter Fischli and David Weiss.

Since then the curator and editor has recorded more than 2,000 hours of discourse with artists, authors, musicians and the most influential creators of our time.

Artists and architects are the focus of Obrist's latest collection. Frank Gehry, Gerhard Richter, Nancy Spero and Zaha Hadid are among the 18 interviewees joining Hockney in the Lives of Artists, Lives of Architects

“For many artists in the book I had known them for twenty years or more,” says Obrist. “I met Nancy Spero while I was still a student. She was like a mentor to me until her death in 2009.

“There is a one-off conversation with Ernest Mancoba, where in one very long session we cover so much ground. For Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian, we had a really intense three year period of conversation taking place all over the world.

“I met David Hockney recently, when I moved to London in 2006, and I went to see him in South Kensington for our first conversation.”

Obrist favours the word ‘conversation’ over ‘interview’ to describe these discussions. Taking place in studios, cafes, planes and train journeys, he records them wherever they occur. But any informality of location should not suggest a casual approach to the process.

Obrist's preparation is careful and methodical. He says “Being able to listen” is the key to his dialogues.

“When I began these conversations, I always used to ask very long questions,” he explains. “Sometimes the questions were longer than the answers.

“I soon learnt that the question should be very short and concise, they are just triggers, or a catalyst, and that the interviewer needs to disappear in a way.

“I always meticulously research everything I can find on the artist, architect, scientist, or philosopher. I read all the conversations they have done before, because often they say similar things. It’s important to talk about the things which maybe have not been addressed.”

Obrist says his goal with the conversations is to allow artists to be seen in “full creativity”.

“As Etel Adnan says it's ‘all about listening to the arts’, he adds. “My work is about managing to underline the importance of art and to single it out from other human endeavours, as something of paramount importance; and to bring in an instinctive and profound love, a generosity of spirit, that also gets extended to other fields of human expression, and that’s really what my project does.”

Since his first art exhibition in 1991, held in the kitchen of his student flat, Obrist has achieved unparalleled renown as an international curator. Currently Co-director of London’s Serpentine Gallery, the project allows him to continue to learn and pursue a passion for artists’ writing.

“When I was growing up, the books of Francis Bacon and David Sylvester were really essential, but also Brassai with Picasso, or Pierre Cabanne with Duchamp. Besides the artists voice in conversations, there is also artists who often write, such as Kandinsky.

“When I studied Art, I would often read the writing of artists, so now it’s hugely interesting to be in a position to edit the same writings.”

In conversation with Hockney, Obrist suggests that he should publish a “manifesto” of his own written work.

“For Hockney as a painter, he says he often makes a detour, such as writing a scholarly book, or directing a film, but it always brings him back to painting, and a new exhibition is triggered by it.

“It was his insatiable curiosity to use new technologies, such as the fax machine, then to use computers, and now his drawings on the iPad. It would be so exciting to have a collection of his writings.

“There are many things I learn during conversations. The Conversation Project is my endless school, life is an endless university, and I am still a student.”

Related Links

-

![]()

Art UK

See a selection of David Hockney's artwork from the 1950s to the 2000s held in Britain's public art collections.

-

![]()

David Lodge in conversation

The author speaks to Obrist ahead of the publication of his memoir, Quite A Good Time To Be Born.

Art and Artists: Highlights

-

![]()

Ai Weiwei at the RA

The refugee artist with worldwide status comes to London's Royal Academy

-

![]()

BBC Four Goes Pop!

A week-long celebration of Pop Art across BBC Four, radio and online

-

![]()

Bernat Klein and Kwang Young Chun

Edinburgh’s Dovecot Gallery is hosting two major exhibitions as part of the 2015 Edinburgh Art Festival

-

![]()

Shooting stars: Lost photographs of Audrey Hepburn

An astounding photographic collection by 'Speedy George' Douglas

-

![]()

Meccano for grown-ups: Anthony Caro in Yorkshire

A sculptural mystery tour which takes in several of Britain’s finest galleries

-

![]()

The mysterious world of MC Escher

Just who was the man behind some of the most memorable artworks of the last century?

-

![]()

Crisis, conflict... and coffee

The extraordinary work of award-winning American photojournalist Steve McCurry

-

![]()

Barbara Hepworth: A landscape of her own

A major Tate retrospective of the British sculptor, and the dedicated museums in Yorkshire and Cornwall