The price of civilisation: Would you die for art?

27 February 2018

When Islamic State fighters overran the Syrian city of Palmyra in 2015, they set about destroying its historical treasures. But some residents refused to bow to their will, even under threat of deadly violence. Who are the people willing to risk their lives for art?

After Islamic State fighters captured the Syrian city of Palmyra in May 2015, the group began to demolish parts of the Unesco World Heritage Site that it deemed to be idolatrous. IS advertises its demolition of such sites for propaganda purposes, but there is also a financial motive - the looting and selling of antiquities has been a significant source of funding.

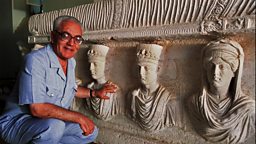

For Khaled al-Asaad, the stones and statues and columns of Palmyra were more than simply an ensemble of antiquity.Simon Schama

Militants from the Islamic State group interrogated Khaled al-Assad, the retired director of antiquities, on the whereabouts of the city's artworks. The 81-year-old refused to cooperate. He was later beheaded in one of the town's squares.

"For Khaled al-Asaad, the stones and statues and columns of Palmyra were more than simply an ensemble of antiquity", observes Simon Schama in the first episode of Civilisations. "He didn’t need a Unesco certificate to tell him that the significance of Palmyra was at once both local and universal; it’s there for believers and unbelievers and east and west."

What is so special about this place? According to Unesco, Palmyra is one of the most important cultural centres of the ancient world. In the 1st and 2nd centuries a range of cultures fused together – Greco-Roman, Persian, Semitic, Indian and Chinese – to create a fabulous trading city in the middle of a desert.

Palmyra's remote location meant the city avoided the impact of creeping urbanisation, leaving the site in excellent condition. "There are very few sites in the Roman world that have this much architecture intact," says Stephennie Mulder, an archaeologist at the University of Texas at Austin, "you can essentially walk into a 2,000-year-old city".

One of the most significant losses was the Temple of Bel. Unesco considered this to be one of the most important religious buildings in the region. Maamoun Abdul Karim, the head of the Syrian Department of Antiquities and Museums, described its destruction as a "catastrophe".

Khaled al-Assad was an expert on this place, to the extent of being fluent in Aramaic, the ancient language of Palmyra. He had looked after its ancient ruins for more than 40 years and was an "icon of Palmyrene archaeology... essentially he was 'Mr Palmyra'", according to former Syrian antiquities official Amr al-Azm.

Khaled al-Assad was not alone in protecting Palmyra, as many others also put themselves in harm's way to protect the city's heritage. The BBC's Middle East editor Jeremy Bowen interviewed two of them: Khalil Hariri was part of a group of local men who, as forces approached, smuggled 400 antiquities out of the city under heavy gunfire. Mohammed al-Assad, Khaled's son, said they were unable to move larger structures and pieces.

Iraq's National Museum a casualty of war, 2003

In 2003, Donny George Youkhanna held a position at the State Board of Antiquities and Heritage in Iraq. When the US invaded and fighting in Baghdad was imminent, a plan was formulated to protect the National Museum. Employees guarded the building and its artefacts on shifts from night to night.

With missiles raining on the communications building opposite, the remaining few people took refuge in the National Museum's basement.

It soon became too dangerous to travel openly in the city, and the workers and researchers assigned to protect the museum began to drift away. The plan was failing but Youkhanna chose to stay, along with the chair of the Antiquities Board, Dr Jabir Khalil Ibrahim.

With missiles raining on the telecoms building opposite, the remaining few people took refuge in the museum basement. When they spotted three men in the museum gardens carrying RPGs and machine guns, aiming to confront American tanks, it was time for George and Khalil to leave.

Inevitably, the museum was looted and many precious artefacts disappeared. Dr. George, who dropped his last name in professional circles, managed to return to the museum a few days later, as explosions shook the city and bridges were destroyed. His attempts to persuade US soldiers to stop the looters were unsuccessful. Although the facts around the museum's losses became disputed, the US protection of the oil fields while stores of human knowledge and art were left open to exploitation was much criticised.

Soon after, George was named Director of the Museum and carried out important work investigating the thefts and preventing sales at international auction houses. Ultimately over a third of the stolen objects were brought back to Iraq.

George fled to Syria in 2006 after death threats against his son, and then moved to the United States where he was appointed Visiting Professor of Anthropology and Asian Studies at New York's Stony Brook University. Donny George died of a heart attack in 2011, aged only 60.

Facing down destruction in Egpyt

This is my museum... our museum... I took the situation in hand.Monica Hanna

It is not only Syria and Iraq where people have taken great personal risks to save valuable artefacts.

During the 2013 coup in Egypt, archaeologist Monica Hanna and her friend Safa drove for hours through fighting between rebels and the security forces. Their goal was the Mallawi City Museum in central Egypt, which had been attacked by looters.

Egypt has a dedicated antiquities police force but, in the chaos that followed the coup, museum security was not a top priority. Monica and Safa took it upon themselves to act. Hanna says, "the security forces were defending themselves, or were defending other institutions – no-one was really giving attention to the museums."

"This is my museum, this is our museum, this should not happen to it. We should just not leave it up to the government to react because apparently they're afraid or reluctant to do anything about it... I took the situation in hand."

When they reached the museum, which sits on the banks of the Nile a few hours south of Cairo, they found that many artefacts had been stolen and destroyed. But then Monica and Hanna found themselves face-to-face with protesters seeking to vent their frustration, who told her, "the government is killing our people and this is our chance to take revenge from the government."

How did Monica respond?

She tells her dramatic story in full on the brand new Civilisations Podcast. The first episode will be released on Thursday 1 March, with new episodes landing weekly thereafter.

-

![]()

The Civilisations Podcast

Viv Jones sparks your imagination with stories inspired by the series

Art and World War Two

I intend to plunder, and to do it thoroughly.Hermann Göring, leading Nazi

The Nazis stole significant works of art during their occupation of various European countries. Soldiers dubbed the Monument Men were charged with recovering them after the Allies landed in Europe in 1944.

Rose Valland gathered vital intelligence that helped in the retrieval of many stolen works. Valland's job at the Jeu de Paume Museum in Paris, coupled with German language skills, enabled her to keep track of where many artworks were sent, despite the great risk to her life had her efforts been discovered.

It was not only in France that art was at risk. In the Netherlands, for example, extraordinary steps were taken during World War Two to protect treasured works such as Rembrandt's The Night Watch.

A number of works were removed from museums and galleries and taken to a secret hidden bunker for safekeeping.

Future conflict

The US military was criticised for its failure to protect Baghdad's National Museum following the invasion in 2003. There are people in the British military who want to be better prepared to protect art in conflict zones.

Lt Col Tim Purbrick, an Army reservist and art expert who was a tank commander during the Desert Storm campaign, has a plan for how the British Army could better preserve art in future wars: a dedicated unit of cultural protection specialists.

He told Radio 4's Front Row that a database of cultural properties across the world is required, so that they aren't targeted by bombs and "are protected when we get to those places".

Such a unit would need to recruit people with specialist skills in many areas – monuments, fine arts, archivists, manuscripts, librarians, archaeology, art conservation, art logistics, art crime investigations and languages.

More from Civilisations

-

![]()

Hue knew? Five surprising facts about colour

Colour is a complicated and, at times, controversial topic.

-

![]()

Explore masterpieces of European painting

Five of the most significant paintings in the history of Western art.

-

![]()

Order a free poster from the Open University

OpenLearn, the OU’s home of free learning, helps you explore the art of different civilisations of the world.

-

![]()

Digital innovations

Explore artefacts using the augmented Reality (AR) app and 360 degrees videos, plus storytelling collaborations with UK museums and galleries.

-

![]()

The Czech and the Chieftains

How the Māori community turned the tables on colonial art.

-

![]()

9 fascinating facts from The Civilisations Podcast

Viv Jones' audio companion to the BBC Two series is taking us on some intriguing tangents.

-

![]()

The Inside Story

Mary Beard and Simon Schama reveal the inside story of writing and presenting the BBC Two series Civilisations.

-

![]()

Civilisations: Box set

Watch all nine episodes of the series on BBC iPlayer.