What's the big idea? Five bizarre pieces of conceptual art

16 September 2016

As part of BBC Four's Conceptual Art season, DR JAMES FOX is presenting his guide to the subject with Who's Afraid of Conceptual Art? – a kind of help for the perpetually perplexed. Here, Fox picks five of the more extreme examples of conceptual art to discuss. Along the way he provides food for thought - or ammunition - for those who find themselves either bemused or irritated by the whole idea of it. And he’s not afraid to ask the big questions: was Duchamp extracting the pee with his urinal? And is conceptual art just a can of excrement?

Conceptual art has bemused, irritated and infuriated the public for the best part of a hundred years. The oracle that is the Tate defines conceptual art as being ‘art for which the idea (or concept) behind the work is more important than the finished art object.’ Many people would instead define it as a load of unmentionables.

I can see where they’re coming from. I’ve been studying art history for almost twenty years and I still don’t get it. Not completely, anyway. But to borrow (and adapt) Richard Feynman’s famous line about quantum mechanics: if you think you understand conceptual art, you don’t understand conceptual art.

Ultimately, I’ve concluded that the best strategy is to embrace conceptual art’s many mysteries and see where they lead. So here are some of its most bizarre examples.

Alphonse Allais

First Communion of Anaemic Young Girls in a Snowstorm, 1883

Conceptual Art didn’t officially start until the 1960s, but it had plenty of predecessors. One of my favourites was a nineteenth-century French humorist called Alphonse Allais.

Allais would do anything for a laugh.

In the 1880s he turned his mischievous attentions to art, exhibiting a series of completely abstract monochrome pictures.

He called his all-white picture First Communion of Anaemic Young Girls in a Snowstorm.

And he called his all-red picture Apoplectic Cardinals Harvesting Tomatoes by the Red Sea.

Allais was joking, of course. But he was also making a point that became really important to conceptualism: the image is largely irrelevant; what matters is the idea behind it.

Marcel Duchamp

Fountain, 1917

It’s often called the most influential artwork of the twentieth century.

Whether Mr Mutt with his own hands made the fountain or not has no importance, he CHOSE it

At some point in 1917 Marcel Duchamp got hold of an American-made Bedfordshire-model urinal, signed it (with the name R. Mutt), called it Fountain, and then submitted it to the Society of Independent Artists exhibition in New York.

It didn’t go down well. In fact, it wasn’t even allowed to go on display.

But Duchamp’s allies immediately understood its importance. ‘Whether Mr Mutt with his own hands made the fountain or not has no importance’, they wrote; ‘he CHOSE it. He took an ordinary article of life, placed it so that its useful significance disappeared under the new title and point of view – created a new thought for that object’.

In the world of conceptual art, it’s the thought that counts.

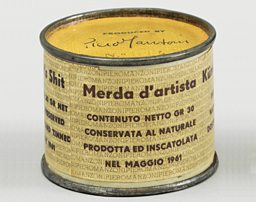

Piero Manzoni

Merda d'artista, 1961

Conceptual artists have always had a thing for bodily waste.

It made Manzoni’s faeces about two hundred times more expensive than its weight in gold

In May 1961 the Italian artist Piero Manzoni filled ninety tins with thirty grams of his own excrement. He labelled the tins Artist’s Shit and then sold them for the price of gold. You might think his asking price was rather optimistic. But it wasn’t.

In 2015 Christie’s sold tin number 54 for £182,500. That made Manzoni’s faeces about two hundred times more expensive than its weight in gold.

Manzoni wanted to show that modern artists had a Midas touch. With a clever idea, they had the power to transform even the most worthless materials into globally coveted commodities.

Joseph Beuys

I Like America and America Likes Me, 1974

Conceptual artists tend to be a bizarre bunch, but few were more unusual than the German Joseph Beuys.

Beuys spent three days in a locked room with a wild (and often irritable) coyote

Beuys had been a Luftwaffe gunner during the Second World War. In 1944 he’d been flying over the Crimea when he was shot down. He miraculously survived the crash, and claimed he’d then been nursed back to health by Tatar tribesmen.

He might have been exaggerating.

One of Beuys’s most important pieces was I Like America and America Likes Me. Beuys was flown to New York, wrapped in felt and taken by ambulance to a gallery where he spent three days in a locked room with a wild (and understandably irritable) coyote.

He was then covered up again and flown straight back to Europe.

Beuys pioneered a new brand of conceptual art with this piece, now known as performance art, where actions rather than objects comprise the art.

Fat and Felt

Beuys' mystical reinterpretation of his wartime crash-landing involved being covered in fat and wrapped in felt, materials which he imbued with spiritual significance and used throughout his career - along with earth, honey, blood, and even dead animals.

Gormley on Beuys

-

![]()

The Essay: Plight

Artist Antony Gormley explores Joseph Beuys' installation Plight

Beuys in Britain

-

![]()

Odd Couple

How Joseph Beuys and Richard Demarco changed British art

Chris Burden

Shoot, 1971

Some artists pushed the idea of the action, or performance, to its violent extremes.

The American Chris Burden was something of an adrenaline junkie. He crawled through a floor of broken glass, suspended himself above an electrified pool of water, and almost set himself on fire – all in the name of art.

And, in November 1971, he even had himself shot.

After assembling a group of friends in a small gallery in California, Burden stood nervously against a wall. An assistant then aimed a .22 calibre rifle at Burden’s left arm and fired.

The astonishing grainy video of the event confirms that he didn’t miss. Burden dashes off screen clutching his wound.

Watch: A New York Times short film on Shoot including video of the event

Listen: Chris Burden speaks to BBC World Service's Witness about the the ideas behind Shoot

More on conceptual art

-

![]()

Vic's Wheel of Dada

Jim Moir - aka Vic Reeves - explores the many sides of Dada

-

![]()

It's OK to be weird

The extraordinary life of performance artist Bob Parks

-

![]()

Marcel Duchamp in 1968

An extended interview with Joan Bakewell on Late Night Line-Up

-

![]()

Anarchy + Absurdity

Visiting Cabaret Voltaire for Dada's 100th anniversary

More on conceptual art

-

![]()

Vic's Wheel of Dada

Jim Moir - aka Vic Reeves - explores the many sides of Dada

-

![]()

It's OK to be weird

The extraordinary life of performance artist Bob Parks

-

![]()

Marcel Duchamp in 1968

An extended interview with Joan Bakewell on Late Night Line-Up

-

![]()

Anarchy + Absurdity

Visiting Cabaret Voltaire for Dada's 100th anniversary

More from BBC Arts

-

![]()

Picasso’s ex-factor

Who are the six women who shaped his life and work?

-

![]()

Quiz: Picasso or pixel?

Can you separate the AI fakes from genuine paintings by Pablo Picasso?

-

![]()

Frida: Fiery, fierce and passionate

The extraordinary life of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, in her own words

-

![]()

Proms 2023: The best bits

From Yuja Wang to Northern Soul, handpicked stand-out moments from this year's Proms