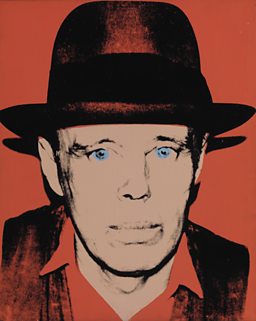

Odd couple: How Joseph Beuys and Richard Demarco helped change British art

15 August 2016

With no less than three Edinburgh exhibitions showcasing his work, German painter, sculptor and performance artist Joseph Beuys is being comprehensively celebrated in Scotland’s capital city. Far from being a summer fling, Beuys and Edinburgh have a long association thanks to a Scottish ex teacher-turned-gallery owner. Richard Demarco met Beuys in Germany and persuaded him to host his debut UK exhibition at the Edinburgh Festival in 1970. As WILLIAM COOK discovers, this unlikely friendship helped transform British art.

Joseph Beuys foresaw a world where everyone can be an artist. Thirty years since his death, has his prophecy come to pass?

Today, anyone with a smartphone can be a photographer or a filmmaker. Anyone with a computer can make a piece of music or a work of art. And now three new shows at the Edinburgh Art Festival pay tribute to this visionary German artist, and the visionary Scotsman who played a key role in his career.

Luckily for Demarco, Beuys was fascinated by Scotland. For him, it was a land of ghosts and witches

‘I was a primary school teacher,’ says that Scotsman, Richard Demarco. ‘Every child at primary school is an artist – then they go to secondary school and it’s knocked out of them.’

Beuys was fired from his German teaching post because he invited everyone he met to join his sculpture class. He believed anyone could be creative. He changed Demarco’s life.

When Demarco first met Joseph Beuys, in West Germany in 1968, Beuys was already an established artist on the Continent, but in Britain he was virtually unknown. Demarco had quit teaching to become an artistic impresario. He persuaded Beuys to make his UK debut at the 1970 Edinburgh Festival. It was the advent of a friendship which transformed British art.

‘He was a man of towering intellect,’ declares Demarco, as he takes me on a tour around these three shows. ‘He was, for me, the Leonardo da Vinci of the 20th Century.’

They seemed an unlikely couple, but the Scots impresario and the German artist actually had quite a lot in common. Born in Edinburgh, of Italian descent, Demarco was a sort of exile. Disillusioned with his native Germany, Beuys was like an exile in his own country. ‘We had absolute confidence in each other,’ says Demarco.

Demarco regarded Beuys as the first artist of the 21st Century. ‘I hadn’t the faintest idea what he was doing – but I knew it was the most important thing I’d ever seen.’

Luckily for Demarco, Beuys was fascinated by Scotland. For him, it was a land of ghosts and witches - the land of Macbeth. ‘When shall we two meet again?’ asked Demarco, with a nod to Shakespeare. ‘In thunder, lightning, or in rain,’ replied Beuys. The gig was on.

As Demarco was quick to recognise, Beuys was really an old-fashioned mystic. A founder of the German Green Party, he was more interested in mythology than modernity. He saw himself as a teacher, not an artist. In fact, he was more like a shaman or a priest.

Beuys is the author of his own legend. Fact or fiction? Who cares?

‘He said the flow of money through the body of society is like poison running through the bloodstream of a human being, and it will destroy all social structures. It’s only a matter of time. He’s right. That’s why the world’s in such a mess.’

How To Explain Pictures To A Dead Hare was an iconic example of his work. Covered with honey and gold leaf, Beuys sat in an empty gallery for three hours, cradling a hare’s carcass, talking about art. Brilliant or nonsense? Well, that’s a matter of opinion - but there was no denying it was different. Nobody had ever seen anything like this before.

At his Edinburgh debut in 1970, Beuys presented one of his most celebrated artworks – Das Rudel (The Pack) featuring a procession of sledges emerging from a VW camper van. Each sledge bore a felt blanket, a reference to the central event of his life.

During the Second World War, while fighting for the Luftwaffe on the Eastern Front, Beuys was shot down and badly injured. His life was saved by Tartars, who dressed his wounds with felt bandages – or so he said.

Art historians have since cast doubt on the veracity of this story. Beuys was shot down and injured, but it seems he was rescued by the Wehrmacht and treated in a field hospital. For his critics, such embellishments expose him as a charlatan. For his acolytes, they merely bolster his mythic status. Beuys is the author of his own legend. Fact or fiction? Who cares?

Beuys made a big splash in Edinburgh in 1970. The critical reaction was mixed, but everyone realised this was something new. Today performance art is commonplace, but back then it was revolutionary. Would contemporary art be quite the same without Demarco and Beuys?

Demarco brought Beuys to Edinburgh eight times in all. In 1973, he gave a twelve hour lecture, from noon until midnight. In 1980, he met up with Jimmy Boyle, the convicted murderer turned sculptor, and went on hunger strike to protest about the conditions of his imprisonment.

The Summerhall show is a treasure trove of personal ephemera from Demarco’s long association with Beuys

Why did Beuys like Edinburgh so much? Why did he keep returning here, time after time? ‘He liked the landscape – he liked the volcanoes,’ reveals Demarco. ‘He liked the light, and he liked the fact that it was the beginning of a journey to the Celtic world.’

On his final visit, in 1981, he made a sculpture from the doors of Demarco’s old studio – a former Poorhouse. He died five years later, of heart failure. He was 64 years old.

These three new exhibitions complement each other perfectly. One is at Summerhall, the veterinary school turned arts centre where Demarco has an office. The other two are at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art.

The Summerhall show is a treasure trove of personal ephemera from Demarco’s long association with Beuys, including photos of their epic trip to Rannoch Moor, where Macbeth met the witches.

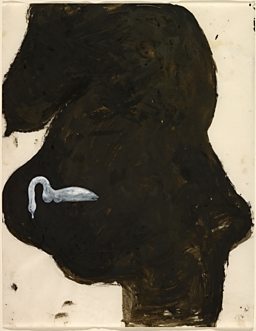

The main show at the Gallery of Modern Art is Joseph Beuys - A Language of Drawing, which comprises over a hundred of Beuys’ enigmatic sketches. It’s an intriguing insight into the work of a man who’s better known for his art happenings, but my favourite show, by far, is the smaller one downstairs.

Richard Demarco & Joseph Beuys – A Unique Partnership is a vivid evocation of a relationship which helped to inspire some of Beuys’ most memorable works.

Beuys’ felt suit is here, and one of his famous sledges, but the best bits are the letters and photographs and newspaper cuttings, which conjure up the spirit of a more idealistic, optimistic age.

Richard Demarco & Joseph Beuys – A Unique Partnership is at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art until 16 October.

Joseph Beuys – A Language of Drawing is at the same gallery until 30 October.

Joseph Beuys x 1000 is at Summerhall until 30 September.

More Joseph Beuys

Related Links

-

![]()

Odd couple

How Joseph Beuys and Richard Demarco helped change British art

-

![]()

Every Woman Dazzles in Leith

Watch the Dazzle Ship's timelapse transformation in Leith

-

![]()

Disobedient, marvellous and degenerate

Surreal Encounters at the Edinburgh Art Festival

-

![]()

The Scottish Endarkenment

Ian Rankin and Kirsty Wark at Art and Unreason, 1945 to the Present

More from BBC Arts

-

![]()

Picasso’s ex-factor

Who are the six women who shaped his life and work?

-

![]()

Quiz: Picasso or pixel?

Can you separate the AI fakes from genuine paintings by Pablo Picasso?

-

![]()

Frida: Fiery, fierce and passionate

The extraordinary life of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, in her own words

-

![]()

Proms 2023: The best bits

From Yuja Wang to Northern Soul, handpicked stand-out moments from this year's Proms