Japan and beyond: 10 manga titles to start your collection

8 August 2018

Although manga originated in Japan, it is a cultural force throughout Asia. In his new book, Mangasia, PAUL GRAVETT examines the creative explosion across the region. Here he picks 10 graphic novels that are ideal for newcomers, and explains more about the origins of the genre.

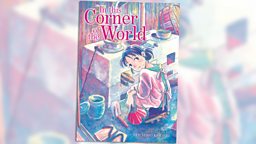

Japan: In This Corner of the World by Fumiyo Kouno

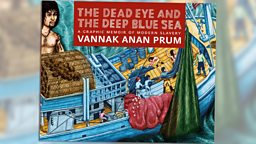

Cambodia: The Dead Eye and the Deep Blue Sea by Vannak Anan Prum

China: My Beijing: Four Stories of Everyday Wonder by Nie Jun

Japan: A Distant Neighbourhood by Jiro Taniguchi

South Korea: Bad Friends by Ancco

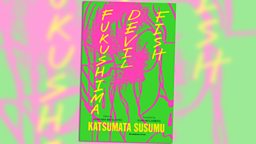

Japan: Fukushima Devil Fish by Susumi Katsumata

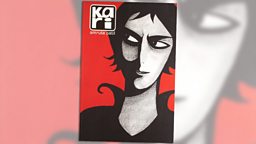

India: Kari by Amruta Patil

Philippines: Mythology Class by Arnold Arre

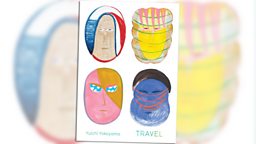

Japan: Travel by Yuichi Yokoyama

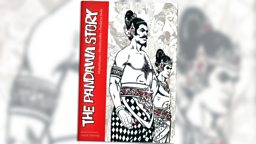

Indonesia: The Pandawa Story by Teguh Santosa

What is manga?

The key features of manga include: dialogue-driven plots; typeset speech balloons, complemented by abundant hand-lettered sound effects; the use of symbols such as sweat-drops and swollen veins to portray emotions; popular characters typified by large eyes and flowing hair; and ‘decompressed’ stories told moment by moment.

Such core elements have had a profound effect on the development of Asian comic art, from the conscious tributes of Chinese manhua and Korean manhwa to comic art as far afield as India and Indonesia.

One word, many variations

Over time, manga has proved an almost infinitely variable art form, embracing subjects that range from children’s stories to gritty autobiographies and no-holds-barred adult content.

There is no single type of manga – just as there is no single Asia

There is no single type of manga – just as there is no single Asia, but rather a diverse range of countries, territories and city-states over which there extends a network of historical, political and spiritual cultures. These are interconnected yet also disparate and sometimes divisive.

‘Mangasia’ is the collective term for all the comic art produced in Asia. It is a way of describing the web of artistic traditions, current trends, social and political structures, histories, beliefs and folklore that provide fuel for the brightly burning flame of Asian comics.

Tricky translations

In recent decades, manga has been exported and imitated around the world. But although comics may have become an international language, Japanese has not.

Although comics may have become an international language, Japanese has not.

Many of the nations that have embraced manga in translation have had to overcome the problems posed by rendering a format that traditionally flows right-to-left and top-to-bottom into the form most comfortable for their particular readership.

Techniques such as flipping (printing mirror images of manga panels so that they can be ‘read’ left-to-right) often lead to inconsistencies between the text and the pictures, while following a story from right to left feels distinctly alien to many readers outside Japan.

Often, hand-drawn side effects in manga are not translated from the original Japanese, as this would mean redrawing the text, so that much translated manga retains the distinct flavour of its country of origin. Some translators opt to rearrange panels, but often the results of this practice are far removed from the mangaka’s original vision.

Crossing borders

It could be argued that Japan’s thwarted 20th Century ambition to liberate and unite Asia has come to pass after all, through the ‘soft power’ of a cultural invasion – in particular by the export of manga to most of Japan’s Asian neighbours, in print or online, either officially or as unlicensed versions.

Comics are a bridge between all cultures.Tezuka Osamu

The impact of manga across Asia makes it a fitting springboard for the exploration and celebration of pan-Asian comic art.

As Japan’s most prolific comics creator (and ‘God of Manga’) Tezuka Osamu (1928–89) observed, ‘Comics are an international language, they can cross boundaries and generations. Comics are a bridge between all cultures.’ The pictorial origins and natures of several Asian scripts underscore the universality of combining words and pictures.

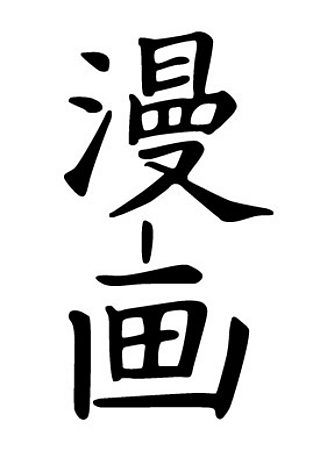

The Chinese have one word – 书, or shū – which can mean ‘to write’, ‘to paint’ or ‘to draw’ (although the language uses other words to further differentiate meaning). It is the ideal verb to describe the hybrid process practised by a mangaka/comic creator (漫 畫家). Appropriately, the same word as a noun means ‘book’.

This is an abridged extract from Mangasia by Paul Gravett, published by Thames & Hudson. He will be appearing at the Edinburgh International Book Festival on 12 August. The exhibition Mangasia: Wonderlands of Asian Comics is on display in Nantes, France until 16 September.

More Manga from the BBC

-

![]()

The manga comic helping Syrian refugees

Obada Kassoumah translates from Japanese into Arabic.

-

![]()

Why do autistic people really love manga?

Dougal Shaw went along to a shop in Glasgow to find out more.

-

![]()

'World's oldest manga' inspires Studio Ghibli anime

It is the story of a frog and hare....

More from the Edinburgh Festivals 2018

-

![]()

Eurovison Young Musicians finalists

Meet the six talented teens headed for the final of Eurovision Young Musicians.

-

![]()

Striking paintings of Edinburgh's past

How sights including Edinburgh Castle have been captured by artists.

-

![]()

10 manga titles to start your collection

Although manga originated in Japan, it is a cultural force throughout Asia.

-

![]()

Why I wander Britain looking for love stories

The musician-turned-storyteller has gathered a huge archive over thousands of miles.

-

![]()

Can you tell the real shows from the fake ones?

Take our quiz and try to separate the genuine titles from the ones we've made up.

-

![]()

22 must-see Edinburgh shows

Performers' picks for the Fringe, International Festival and Book Festival.

-

![]()

'These stories never get to be told'

The Edinburgh Festival Fringe shows putting disability in the spotlight.

-

![]()

BBC at the Edinburgh Festivals

Join us at our hub at George Heriot’s School in the heart of Edinburgh for top shows.

More from BBC Arts

-

![]()

Picasso’s ex-factor

Who are the six women who shaped his life and work?

-

![]()

Quiz: Picasso or pixel?

Can you separate the AI fakes from genuine paintings by Pablo Picasso?

-

![]()

Frida: Fiery, fierce and passionate

The extraordinary life of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, in her own words

-

![]()

Proms 2023: The best bits

From Yuja Wang to Northern Soul, handpicked stand-out moments from this year's Proms