Spine tingling: 80 years of Penguin paperbacks

26 February 2015

Affordable, unabridged, pocket-sized, Penguin Books weren’t the first paperbacks but they were the most ambitious. Now in its 80th anniversary year, BRIAN MORTON flicks through the publisher’s colour-co-ordinated, avian-obsessed history.

Sometimes a movie moment can sum up a whole culture. Near the start of Running Scared, actor David Hemmings' directorial debut, a hollow-cheeked Robert Powell moons around his Cambridge college rooms while his friend and roommate bleeds to death on his bed, a suicide.

At one point, the camera pans across a neat shelf of sky blue book spines. Student audiences invariably gave a soft laugh at the sight, partly because it defuses the tension of the scene, partly because an alphabetized row of Pelican paperbacks suggested that at least one of these young men had a mind of high - possibly excessive - seriousness, and was studying politics, history, sociology, psychiatry.

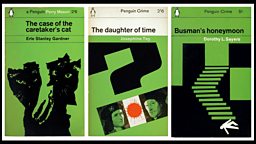

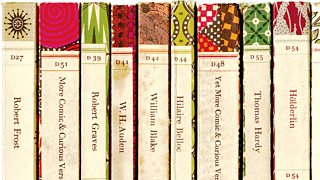

It might have just as easily have been a row of orange spines, the more familiar livery of Penguin Books, which were part of pretty much ever half-serious reader's furniture in the 1970s. And there were other plumages in the aviary.

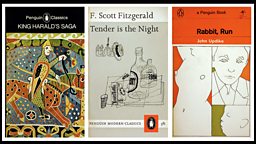

The drab olive no-colour of Penguin Modern Classics would have suggested a major in modern literature or American studies, the clerical black of Penguin Classics an interest in the ancient world but without the Latin, Greek or Sanskrit to attempt the originals.

There might have been a splash of Penguin Crime, strychnine green, and maybe a highbrow, large format Peregrine or two. There probably wouldn't be any Puffins or Kestrels, which would have been left behind in the parental home but maybe nostalgically re-read during the vac.

- Obsessive Designs: From Penguin to Picador, Pan and Beyond

Classic paperback designs and the artists who created them

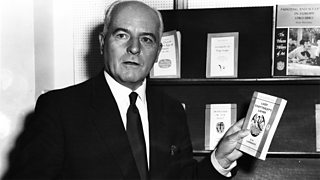

The ubiquity of Penguin books in modern British publishing conceals a paradox best expressed by founder Allen Lane's colleague and biographer Jack Morpurgo, who said that even in Allen Lane's lifetime, Penguin became "the least typical member of the genus it was said to have created".

There had been paperbacks before Penguin - all French books were paperback for instance and Woolworth's, soon to be a key outlet for the new imprint, sold their own cheap editions - but few ranged so eclectically and wide.

Though Lane was not a conventionally bookish man, and pretended to be far less literate than he was, the rapidly growing catalogue was deeply imprinted with his complex personality. Richard Hoggart noted that the Morpurgo biography applied no less than 53 mostly contradictory adjectives to Lane ("harsh", "malicious", "bland", "vulnerable", "genius", "spontaneously benevolent" touch the extremes) and a similar number could easily be applied to the Penguin list.

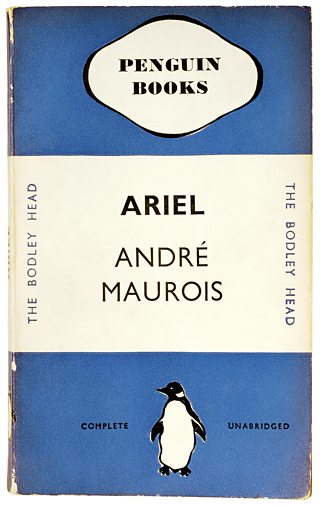

The word that Lane and his brothers Dick and John kept in view was "friendly". Though no great democrat and not in the strict sense a popularizer, it was the Lanes' wish to make the best of world literature available at an attainable price, even if the economics of publishing sometimes dictated an inevitable loss. The appearance in the founding list of a Shelley biography, André Maurois's Ariel (liveried in dark blue rather than orange) alongside Agatha Christie and Eric Linklater doesn't suggest a potboiling or bodice-ripping catalogue was in the offing.

A mere procession of titles doesn't make a list. Various names were touted, and in some cases (Dolphin, Porpoise) rejected because they were already in use.

The appearance in the founding list of a Shelley biography, André Maurois's Ariel (liveried in dark blue rather than orange)... doesn't suggest a potboiling or bodice-ripping catalogue was in the offing

According to Penguin lore, embellished over many lunches and parties, it was secretary Joan Coles who shouted out the name over her partition. The idea was accepted on the spot and Edward Young was despatched to London Zoo to sketch penguins in every attitude from the dignified to the absurd, creating an image which, arrayed left or right according to position, has remained in place ever since.

It was often said of Lane that he had no intellectual interests. The truth was that he was interested in everything, in his role as publisher, at least.

That quality of evenly suspended attention, a near-ideal characteristic in a mass-publisher, allowed him to head in almost any direction he wanted - archaeology, architecture, art . . . - and rely on the knowledge that Penguin had acquired enough identity to "sell by the mark": in other words, the very fact that something came out in Penguin seemed a guarantee of quality.

The downside to this was the "Heinz effect", which dictated that if your are known for 57 fine varieties and then take a risk on an inferior 58th, it will pull you down. It's a mark of Lane's extraordinary instinct for the market and for his authors that this never happened.

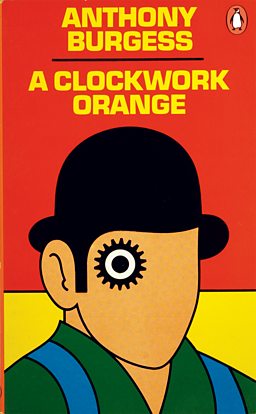

He did, however, skirt close to the wind. Lane had inherited his surname (originally Williams) and a publishing house from John Lane of the Bodley Head, a gifted but erratic publisher who had more than once - with Oscar Wilde's Salomé, with the decadent Yellow Book, and with Herman Sudermann's The Song of Songs - resorted to using the judiciary as publicity managers.

Allen Lane and his brothers inherited the trait, embarrassingly with a faked diplomatic autobiography called The Whispering Gallery, admirably with James Joyce's Ulysses, most famously with Lady Chatterley's Lover, which, bad book though it was, guaranteed the imprint's long-term future and won significant freedom for British writers and publishers.

Up to that point, Penguin's economic future, even with the momentum of Bodley Head's controversial reputation, even with the market support afforded by Woolworth's, had been precarious.

The Lanes were brilliant at skating over balance sheets that didn't add up; skating like penguins, you might say. And they had to do so in the face of strong resistance not just from within the publishing industry, where it was feared that cheap books meant a net devaluation of writing itself, but from writers and critics.

No less a democrat than George Orwell, albeit an Eton-schooled democrat, thought that cheap books would mean fewer books sold. When the opposite turned out to be the case, Orwell, like virtually every detractor before him, was obliged to concede and now Penguin guards his legacy with particular care, repackaging his classic titles for each successive reading generation.

For eighty years, an imprint that broke most of the prevailing rules and survived on optimism, snap judgement, considerable high-mindedness and a lot of fun became that most endearing of all cultural artefacts: something hated by everyone… except the public.

Penguin at 80

-

![]()

Designing obsession

The iconic book designs and the artists who created them

-

![]()

Spine tingling

Brian Morton looks back at the colourful history of Penguin

-

![]()

Translation matters

Anthea Bell on the value of translation in world literature

Related Links