The Glory of Gothic (Part 2)

Dan Cruickshank on the presenters who got medieval

Gothic architecture, or the 'modern style' as it was known 850 years ago, is immensely popular among architectural historians. Broadcaster and art historian Dan Cruickshank appraises its on-screen portrayal over the past 40 years.

In this second part of Cruickshank's look at gothic architecture on television, we meet Jon Cannon and Nikolaus Pevsener. Read part one.

First shown in 1968, Leipzig-born Nikolaus Pevsner visits Cartmel Priory for his 46-volume book series on architecture, The Buildings of England.

In his 2008 series How to Build a Cathedral, Jon Cannon explores who built these magnificent structures. He surveys the 'sensational' 13th century west front of Wells cathedral, bringing to life a wonderful array of Gothic detail, and sheds light on a medieval ritual.

Along the way Dan outlines his own love of the gothic form.

More Gothic on the BBC

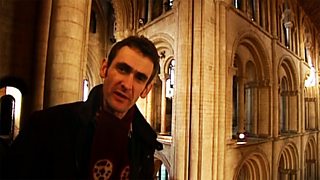

Jon Cannon on Wells Cathedral and Flying Buttresses: How to Build a Cathedral, 2008

This is the most recent programme on BBC television to tackle the wonders of medieval Gothic construction in great and well-informed detail.

A hidden choir made it appear that the statues themselves had started to sing

Jon Cannon clearly knows his stuff and is clear and compelling in his presentation. The thesis for the programme is forceful and dramatic – cathedrals were the wonders of the medieval world, were showpieces of Christian faith and ritual, were the tallest and greatest pieces of construction since the pyramids – and they were built when the vast majority of the European population was living in 'hovels.'

The most memorable cathedrals are in one form or other of Gothic – a radical art and engineering movement that appeared and evolved with incredible speed during the 12th century. What on earth was going on? This programme tackles many of these questions.

The sequence about the sensational 13th century west front of Wells cathedral is splendid. It makes sense of – indeed brings to life – the wonderful array of sculpture and Gothic detail. Ritual in the medieval church was all-important leading to sacred theatre in which the cathedral played a crucial role.

On Palm Sunday clerics processed towards the cathedral, emulating Christ's entry into Jerusalem, and as they chanted the west front of the cathedral seemed to come to life. Within its stone tracery was a hidden choir that, as it responded, made it appear that the statues themselves had started to sing.

As Cannon explains, architecture, sculpture and music all came together so that, for a moment, the cathedral became Jerusalem itself – this was the aim and essence of sacred Gothic art and architecture.

The sequence on the magical beauty of stained glass and gothic structure is inspiring.

The constant quest of Gothic architects was to relieve walls of their structural role so that windows could get larger allowing God's light, manipulated with the hues and imagery of stained glass panels, to flood into the church. This became possible, and windows became bigger, as the Gothic skeletal system of piers, vaults, ribs, pointed arches and buttresses evolved.

Key to this system was the flying buttress that, as Cannon explains succinctly, 'siphoned off' the weight of the nave, and the outward thrust of the nave vault, 'leap frogged' over the lower aisles and took the load to the ground.

Arrays of flying buttresses – of arched form - also helped to keep the building in poise by applying an opposite and roughly equal counter thrust to the thrust of the nave and aisle vaults. Flying buttresses made larger windows possible, vaults higher and arches more delicate in form and decoration.

As Cannon says of flying buttress, 'where practical necessity met aesthetic adventure came strange and fantastic beauty.' Splendid stuff.

Nikolaus Pevsner at Cartmel Priory: Contrasts - Buildings of England, 1968

To see Nikolaus Pevsner at work is marvellous. This utterly admirable German architectural historian set to work in the late 1940s to catalogue, describe and assess the buildings of England.

Pevsner clearly had a talent for the drama of television

A phenomenal challenge undertaken with Penguin books and an ever-changing group of helpers, it was finally completed in 1974 as a 46-volume series of books – the first of which was published in 1951.

It was a truly heroic endeavour that not only gave the English a perception of their own building history but also, because of Pevsner's European perspective and academic objectivity, placed English architecture firmly within the international context.

And, thanks to Pevsner's fondness and respect for British art, the buildings of England - seen through the benign prism of his perceptive gaze - were not found wanting.

Indeed the series of books – that has grown to include the Buildings of Scotland, Wales and Ireland – have given the people of the British Isles an increased sense of pride in their building stock.

This film suggests Pevsner's working method. It reveals his 'restrained factual approach' to compiling his guide as he hones a text that is both 'inventory and commentary.'

The film also, as Pevsner takes the viewer around Cartmel Priory, offers lots of sound tips about how to 'read' ancient buildings and how to date their growth and various 'building campaigns' by identifying and dating significant details.

The slightly quirky thing about the programme is that it suggests that Pevsner dated and read buildings largely through on-site observation of details and connoisseurship. These virtues were no doubt critical and at his command, but Pevsner was a great believer in research, and before site visits he built up a dossier of documentary evidence about the buildings to be assessed.

The film shows him referring to his clip-board of notes but, of course, seeing him checking these is not as televisual as seeing him stalk around the building finding and interpreting luscious architectural details. I love him 'discovering' the west door, and initially being puzzled by the fact that stylistically different details – usually representing different periods – seem at Cartmel to have been produced in different parts of the building at the same time, perhaps even by the same people.

He has a mild eureka moment and it's quite a performance. Pevsner clearly had a talent for the drama of television – with its jeopardy (can he date the building or not?) and revelations. It's a great pity he didn't do more. And he had a wonderful, liltingly refined Anton Walbrook accent – so finely Anglo-German and cultured it almost sounds fake.

More Nikolaus Pevsner

-

![]()

Reith Lecture: Perpendicular England

Nickolaus Pevsner examines the Perpendicular style, formed in England in about 1330, and which he calls 'the most English creation in architecture'.

More Dan Cruickshank

-

![]()

The Family That Built Gothic Britain

The triumphant and tragic story of the greatest architectural dynasty of the 19th century. Dan Cruickshank charts the rise of Sir George Gilbert Scott, the fall of his son George Junior and the rise again of his grandson Giles.

-

![]()

The Bridges That Built London

Dan Cruickshank explores the mysteries and secrets of the bridges that have made London what it is; in this clip the history of Westminster Bridge.

-

![]()

Majesty and Mortar: Britain's Great Palaces

From the Tower of London to Buckingham Palace, Dan Cruickshank tells the story of a thousand years of palace building.

Art and Artists: Highlights

-

![]()

Ai Weiwei at the RA

The refugee artist with worldwide status comes to London's Royal Academy

-

![]()

BBC Four Goes Pop!

A week-long celebration of Pop Art across BBC Four, radio and online

-

![]()

Bernat Klein and Kwang Young Chun

Edinburgh’s Dovecot Gallery is hosting two major exhibitions as part of the 2015 Edinburgh Art Festival

-

![]()

Shooting stars: Lost photographs of Audrey Hepburn

An astounding photographic collection by 'Speedy George' Douglas

-

![]()

Meccano for grown-ups: Anthony Caro in Yorkshire

A sculptural mystery tour which takes in several of Britain’s finest galleries

-

![]()

The mysterious world of MC Escher

Just who was the man behind some of the most memorable artworks of the last century?

-

![]()

Crisis, conflict... and coffee

The extraordinary work of award-winning American photojournalist Steve McCurry

-

![]()

Barbara Hepworth: A landscape of her own

A major Tate retrospective of the British sculptor, and the dedicated museums in Yorkshire and Cornwall