Blue Note at 75: All that jazz

11 November 2014

The best-known label in jazz celebrates its 75th anniversary in 2014. From humble beginnings in New York, Blue Note became famous not only as a purveyor of genre-defining recordings but also as an arbiter of cool, thanks to its distinctive photography and sleeve designs, many of which are collected in a deluxe new illustrated book, Uncompromising Expression. Ahead of a star-studded London concert to mark its milestone birthday, author and jazz critic BRIAN MORTON casts a critical eye over seven and a half decades of Blue Note history.

There are certain immutable rules of cultural life. They dictate that all innovation, even what was once considered avant-garde, very quickly becomes routine; that history repeats itself not necessarily as farce but almost always as anti-climax; and that trying to recover past glories is a fool’s errand.

But then in the summer of 2014 a record appeared that seemed to sweep away fatalism and turn back the clock almost 50 years to the heyday of a label that for some, and sometimes against the evidence, defines modern jazz.

Enjoy The View is an album of tight, soulful modern jazz, led by veteran vibraphonist Bobby Hutcherson. His group consisted of such speed-dial names as saxophonist David Sanborn, organist Joey DeFrancesco, who contribute two tunes each, and drummer Billy Hart, one of the most recorded artists in jazz history.

What made the set seem exceptional, because a new record by Hutcherson isn’t a rarity in itself, was the modest Blue Note colophon in the upper left corner.

No tinted monochrome photograph of the artist on the cover, but still a strong echo of a moment in musical time when "Blue Note", as a concept rather than merely as a marketing tab, stood for artist-led experiment, a collegial approach to recording with a large, informal pool of like-minded players, bold presentation of jazz as an adult art form, and above all technical quality.

Blue Note records sounded – and were – rehearsed. Recordings took place at times congenial to artists who went to bed at sunrise rather than rushing for a commuter train.

Tunes were performed until everyone was satisfied with the result, a level of quality control that left behind a vast Dead Letter Office of “alt. takes” and rejected versions that were quickly called on to fill out CD durations, special editions and all-in retrospectives.

One only has to listen briefly to Enjoy The View to sense the years rolling back: high-wire improvisation in immaculate hi-fi, but quite obviously the bright, very even sound of a modern digital recording, and not from the vault of veteran engineer Rudy Van Gelder in his Englewood Cliffs studio.

If the abstract cover art wasn’t a clue to the provenance, there are others dotted about the sleeve – some helpful, some misleading. That Hart appears “courtesy ECM Records”, the signature jazz label of the 1980s and 1990s, is a clue. There’s an engineering credit for a Frank Wolf, who but for an obvious difference of spelling might be one of the Founding Fathers.

The album was made in Hollywood, a very un-Blue Note location, and the producer, in the absence of checks for Van Gelder, or more recently celebrated names like Michael Cuscuna and Bob Belden, is musician Don Was. He is (and the obvious is/Was pun is played out in the title of one of DeFrancesco’s pieces on the set) the man who has taken on the challenge of steering Blue Note through its next evolution.

Blue Note actually began as a producer of funky, jukebox jazz of the old school

Creative jazz stands higher again than it did a decade or two or four ago – there was a brief boom in the 80s, when a dormant Blue Note returned to recording – and higher on its own terms rather than hybridised with rock, as in the 1970s, or with various world-music and classical forms as in later decades. These latter graftings were something of an ECM speciality.

Everyone tends to forget that Blue Note actually began without much artistic pretension and as a producer of funky, jukebox jazz of the old school.

The label, famously, was founded by German immigrant Alfred Lion, who’d come to the US in 1937 as a young fan (jazz was the pull factor, Hitler and recession were the pushes), experienced John Hammond’s epochal From Spirituals To Swing concert at Carnegie Hall, and decided with his friend Max Margulis to record hot Harlem jazz in the boogie-woogie style.

The first Blue Note recordings were of pianists Meade Lux Lewis and Albert Ammons, who were already borderline old-hat in 1939. Lion and Margulis were soon joined by photographer Frank Wolff (two f’s) and by designer Reid Miles, who by not caring very much about jazz helped to establish its most memorable imagery.

Together they survived military conscription, wartime distortions of the market, a union ban and the implacable economics of jazz recording, and were on hand to capture the new, hard language of bebop.

Strictly speaking, bebop’s real cradle and crib were the tiny Savoy and Dial labels, but Lion was on hand to harness its commercial emergence as “hard bop” and the artists who recalibrated its frenetic pace and racquetball harmonics to make something marketable of it.

Having drummer Art Blakey, soulful pianist Horace Silver and that eternal enigma Thelonious Monk on the strength gave Blue Note critical impetus. And having a saxophonist Ike Quebec, albeit himself a player of more mainstream persuasion, as musical director and A&R man, gave the recording programme focus and direction.

Between 1945 and 1965 Blue Note represented the leading curve of East Coast jazz. Having recorded the veteran Sidney Bechet, the first mature jazz soloist in the modern sense, the label now addressed itself to a new creative confidence and self-determination in African-American music.

And yet there is an irony that disguises other minor-key elements of the Blue Note story. The label’s often unexamined reputation for cutting-edge innovation ignores the awkward detail that the major innovators of modern jazz were only glancingly associated with it.

Neither Miles Davis nor Charles Mingus were “Blue Note artists”. Ornette Coleman made his revolutionary albums for Atlantic and only a handful of dark, but undervalued records for Lion's label. Cecil Taylor, perhaps the most innovative of all, was only briefly involved.

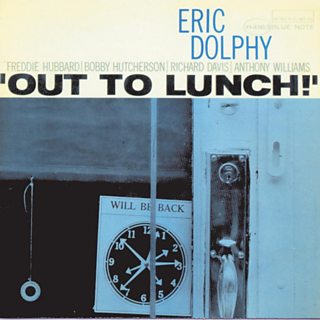

John Coltrane made just one Blue Note record. Eric Dolphy likewise, though his early death in 1964 intervened; that notwithstanding, and with the benefit of Reid Miles’s zany cover, Out To Lunch! is regularly voted greatest jazz record of all time.

The label’s real thrust came through its production of coach-built hard bop rather than avant-garde experiment. Trumpeter Lee Morgan would be the obvious representative example, with Morgan’s great funky The Sidewinder, a record he then continued to remake in different keys for the next decade, as the best candidate for ‘typical’ Blue Note release.

The main downside of Lion’s apparent open-handedness is that musicians like Hutcherson or pianist Andrew Hill, another significant composer, often found themselves recording prodigally on Lion’s dime only to have their most distinctive work shelved as uncommercial, languishing there in some cases for several decades; Hutcherson’s The Kicker, made in 1963, was only released in 1999, and some of Hill’s best work spent similar time in cold storage.

Its finest productions are among the best-loved in American music

The other question mark that hovers over Lion’s otherwise saintly image is his willingness to keep addicted artists indentured to the label by advancing them money for drugs and then calling in the debt in sessions that basically went into the label’s savings account. Indeed, the very fact of a European white man determining artistic policy in an African-American music is ambiguous.

And yet Blue Note survives all revisionist attempts. Its finest productions are among the best-loved in American music. Its covers are a genre. Even studio sweepings are treasured.

At a time when the music business was increasingly dominated by the rock album, Blue Note was taken over by Liberty, only returning as a semi-independent imprint in 1985, with a surge of new jazz recording, led by pianist Michel Petrucciani and the once-fashionable but long-eclipsed Charles Lloyd, who had once played modern jazz to hippy audiences at the Fillmores.

Blue Note went through awkward moments, dabbling with acid jazz and dance-oriented concepts, but jazz’s market status is more stable again, and under Was the imprint can again enjoy not just the view of its own eminent past but the road ahead as well.

• Uncompromising Expression: 75 Years of the Finest in Jazz by Richard Havers is published by Thames & Hudson ahead of an anniversary concert at London's Royal Festival Hall on 22 November featuring Robert Glasper, Jason Moran and more. Havers talks to Don Was in a special pre-show event at 6pm.

More jazz on BBC Arts

-

![]()

Blue Note at 75: All that jazz

Writer Brian Morton casts a critical eye over seven and a half decades of Blue Note history.

-

![]()

Blue Note at 75: Meet the Don

A Q&A with Don Was, the veteran musician appointed Blue Note president in 2012.

-

![]()

Blue Note at 75: Cover stories

Check out ten of the finest sleeves from Blue Note's vast back catalogue.

-

![]()

Jazz Voice: Celebrating a Century of Song

The EFG London Jazz Festival’s spectacular opening-night gala - watch it in full on demand.

Elsewhere on the BBC

-

![]()

BBC Playlists: 75 Years of Blue Note

BBC Radio 6 Music selects some classic and hidden gems from the label.

-

![]()

The Jazz House

Stephen Duffy talks to author Richard Havers about his new book on Blue Note Records.