The Two Roberts: Love, paint and poverty

2 February 2015

Robert Colquhoun and Robert MacBryde were stars of the art world in the 1940s. The two Ayrshire-born painters met on their first day at Glasgow School of Art and became lifelong lovers. In London the hard-drinking pair embraced the bohemian lifestyle of the Soho set, becoming friends with Lucian Freud and Francis Bacon and enjoying considerable success. As a major retrospective of their work continues at Edinburgh's National Gallery of Modern Art, WILLIAM COOK charts the spectacular rise and fall of these enigmatic figures.

Everyone called them The Two Roberts - well, everyone who knew them. Their names were Robert Colquhoun and Robert MacBryde, and they shared everything - their art, their bodies, their lives.

They were lovers, in an era when homosexuality was still illegal. They were big drinkers – you could say they drank themselves to death. Above all they were brilliant painters, and now a stunning new retrospective celebrates their intense relationship, and their mesmeric art.

They worked hard, and played even harder. In Soho, they were free to be themselves.

Half a century since they died, in poverty and obscurity, we're finally waking up to the importance of these neglected artists. As their first joint exhibition proves, it's been worth the wait.

Colquhoun and MacBryde met in 1933 on their first day at Glasgow School of Art. They were both working class lads from Ayrshire. They'd both left school at fifteen.

At art school, Colquhoun was the star pupil. MacBryde came a close second. After art school they went to London, and quickly became the talk of the town. Their pictures were bought by the Tate. They were championed by Kenneth Clark. They were photographed by Vogue.

The 1940s were good to them – very good indeed. They were spared active service in the Second World War (Colquhoun had a weak heart, MacBryde had tuberculosis) and alongside fellow artists like Lucian Freud and Francis Bacon, they became leading players in the Soho scene.

Then as now (but even more back then) Soho was a bohemian enclave in the heart of London where you could do (almost) anything you wanted. They worked hard, and played even harder. In Soho, they were free to be themselves.

And then, just as suddenly, their figurative art fell out of fashion. Collectors, critics and curators turned their backs on Colquhoun's muscular figures and MacBryde’s robust still lives. The big new thing was Abstract Expressionism, a genre entirely alien to them. Their art was still just as good, and getting even better, but now they were all washed up. It was terribly unfair.

At times, especially at the weekends, it all went completely haywire. There wasn’t one stick of furniture that hadn’t been brokenChristopher Barker

It was at this point, in 1951, that they met Christopher Barker. Born in 1943, Christopher is the son of the poet George Barker and the writer Elizabeth Smart (author of By Grand Central Station I Sat Down And Wept).

Elizabeth and George had four children together (Christopher was the second) but by 1951 Elizabeth was raising their children on her own, in a ramshackle old farmhouse in rural Essex called Tilty Mill. There was a radio but no TV, running water but no electricity.

Elizabeth had met the Two Roberts in Soho. They'd been evicted from their studio. Extraordinarily, she invited them to live in Tilty Mill and look after her children while she worked in London. They spent the next four years there.

'At the time, that was incredibly risky,' says Christopher. He was only seven, and attitudes to homosexuality were not nearly as enlightened as they are today. But for The Two Roberts it was a lifeline. Here was a place where they could paint in peace.

Christopher has happy memories of his childhood with the Two Roberts. 'We had no idea that they even slept together.'

But it was an unusual upbringing, all the same. Both men drank heavily, which often led to violent arguments. Unlike MacBryde, Colquhoun was bisexual, and his heterosexual excursions made MacBryde very jealous.

'There'd be huge great rows,' says Christopher. 'Crashing and bashing, all through the night.' Was he scared? 'Yes! Terrified!'

Thankfully, they confined their boozing - and quarrelling - to the weekends, when Elizabeth was back from London, after the children were in bed.

'At times, especially at the weekends, it all went completely haywire,' he chuckles. 'There wasn’t one stick of furniture that hadn’t been broken.'

During the week, when they were sober, they took very good care of them. 'It was like Jekyll & Hyde.' They made them fancy dress outfits. They helped them make puppets out of plasticine. Christopher had nothing to compare it with. 'When you're a child, that's the only life you know.'

As in many marriages, childcare and housework weren't divided evenly. 'Colquhoun did no domestic chores whatsoever,' says Christopher. MacBryde did virtually everything while Colquhoun painted.

Their reputations – and their fortunes – had gone from bad to worse

'I used to peek into the studio, and there'd always be a work in progress.' Despite the cruel indifference of the art world, the quality (and quantity) of Colquhoun's work remained undimmed. With four children to care for, MacBryde had a lot less time to paint, but whatever he painted was superb. 'They influenced each other. MacBryde's work crept into Colquhoun's.'

After a few years, Elizabeth started earning good money as a copywriter, and could afford to bring her children up to London and send them to boarding school. Their Essex commune was no more. Elizabeth paid off their bar bill at the local pub. It came to £1500, an absolute fortune in the 1950s.

Christopher still saw The Two Roberts at his mother's London parties. They were drinking even more heavily. Their reputations – and their fortunes – had gone from bad to worse.

'They had absolutely no money. They were bumming off people all the time.' But they never stopped painting, and finally, in 1962, Colquhoun was offered a new one man show. Their friends hoped this exhibition would turn their lives around.

Heroically, Colquhoun worked flat out to produce the new work he needed for this comeback show. Yet decades of hard living had badly damaged his fragile health. After working through the night, he died in MacBryde's arms. He was only 47.

Elizabeth put up MacBryde at her London flat, where Christopher was living. Without Colquhoun, MacBryde was bereft. 'He was in a terrible state,' says Christopher. 'He wasn’t looking after himself.' He cried and drank and cried, all through the night.

He subsequently moved to Ireland and virtually abandoned painting. In 1966 he was dancing outside a pub in Dublin when he was knocked down and killed by a passing car. He was 53 years old. 'It's a love story,' says Christopher. 'They were together all that time, and when Colquhoun died it's appalling what happened to MacBryde.'

Christopher became a photographer. In 2006 he published a moving memoir, The Arms of The Infinite, about his mother, his family, and The Two Roberts. 'They died in penury,' he says, 'of broken hearts.' It was almost a form of suicide. It's enough to make you weep. 'They never got to realise their real greatness,' says Christopher.

This super show should give you some idea. It's even more than the sum of its two parts. So what did the Two Roberts mean to Christopher, as men as well as artists? 'MacBryde and Colquhoun together, as a unit, became a father, I think, to me.'

The Two Roberts: Robert Colquhoun and Robert MacBryde is at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh until 24 May 2015.

The Two Roberts | Ken Russell for Monitor, 1959

Scottish Painters by Ken Russell

Allan McClelland narrates this 1959 film from the Monitor series

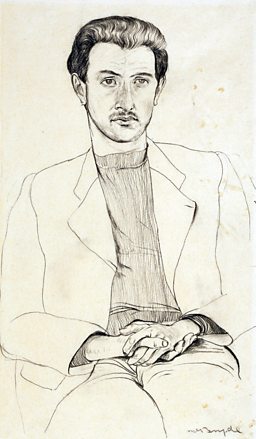

MacBryde by Colquhoun

Colquhoun by MacBryde

Monitor: 2 February 1958

Related Links

MacBryde had, and retained to the end, a capacity to abandon himself gently and totally to the drink and the moment, so that in the right company he achieved incandescence. He had a beautiful voice and a repertoire of Scots songs and he was seldom reluctant to perform... Most of the songs were Robert Burns’ – also of course an Ayrshire man; much of the wording was inaccurate, but he had filled it out for himself over the years with verses which, though they were often almost meaningless, yet were fitting, even somehow deeply moving.Anthony Cronin, Dead as Doornails (1976)

Colquhoun was tall, roughly handsome, every feature open and strongly marked, the sort of long head that one associates with the Scots who have gone around the world as makers, builders and engineers. He was somewhat awkward and almost inarticulate, but his gentleness and warmth came across immediately because when you met him you met almost the whole man.Anthony Cronin, Dead as Doornails (1976)

Art and Artists: Highlights

-

![]()

Ai Weiwei at the RA

The refugee artist with worldwide status comes to London's Royal Academy

-

![]()

BBC Four Goes Pop!

A week-long celebration of Pop Art across BBC Four, radio and online

-

![]()

Bernat Klein and Kwang Young Chun

Edinburgh’s Dovecot Gallery is hosting two major exhibitions as part of the 2015 Edinburgh Art Festival

-

![]()

Shooting stars: Lost photographs of Audrey Hepburn

An astounding photographic collection by 'Speedy George' Douglas

-

![]()

Meccano for grown-ups: Anthony Caro in Yorkshire

A sculptural mystery tour which takes in several of Britain’s finest galleries

-

![]()

The mysterious world of MC Escher

Just who was the man behind some of the most memorable artworks of the last century?

-

![]()

Crisis, conflict... and coffee

The extraordinary work of award-winning American photojournalist Steve McCurry

-

![]()

Barbara Hepworth: A landscape of her own

A major Tate retrospective of the British sculptor, and the dedicated museums in Yorkshire and Cornwall

Art and Artists

-

![]()

Homepage

The latest art and artist features, news stories, events and more from BBC Arts

-

![]()

A-Z of features

From Ackroyd and Blake to Warhol and Watt. Explore our Art and Artists features.

-

![]()

Video collection

From old Masters to modern art. Find clips of the important artists and their work