Shakespeare's men welcomed - then banished

The King's Men, Shakespeare's troupe of performers for which he wrote most of his plays, came to Bridport in Dorset as part of a summer tour of the southwestern counties in 1621, five years after The Bard's death.

But just three years later, in 1624, they returned only to be turned away by local officials.

-

![]()

Much ado near me

Hear more Shakespeare stories on BBC Radio Solent

-

![]()

Shakespeare Festival 2016

The BBC celebrates the genius of the bard

Shakespeare’s acting company played on as probably the most prestigious troupe in the land – with the playwright's whole canon of works available to them on tour.

Bridport, along the south coast between Southampton and Exeter, had prospered for more than a century primarily because of the high quality of the hemp and flax grown nearby, the raw materials for the manufacture of ropes and sailcloth.

The town was so famous for this industry that an early 16th-century morality play, Hickscorner, mentioned the rope… as the ideal stuff for a high quality hangman's noose!

Where might the King’s Men have performed?

No record of where The King's Men performed in Bridport survives, but judging by the evidence from other boroughs in Dorset, a variety of places would have served their turn. In nearby towns, travelling troupes played in the private homes of leading burgesses and in the country houses of local gentry. They put on their plays in churches, in guildhalls (which they rented for the occasion), in schoolhouses, in church-houses, and at least once, when no public venue could be secured, in an inn.

The rise of a Puritan faction in the town was probably what prevented them from performing in 1624Ted McGee REED

Churches that survive from Shakespeare's time - St. Michael's in Lyme Regis, St. Mary's in Beaminster, and St. John the Baptist's in Bere Regis - provide a glimpse of how attractively spacious these playing places were. So too does the church-house of Sherborne: the open second storey room, 116' x 19' with a ceiling that rose from 7' at the walls to a peak over 18' high, controlled access, a fireplace for warmth, good light from a bank of windows on the south side, and the furniture to accommodate large gatherings, as it did for the town's annual Whitsun ale with its customary 'King of Bridport'.

Wherever The King's Men performed in Bridport, their performance and its reception must have been successful, for they returned in 1624 and again in 1625. In 1621 and 1625, the town paid the players 5s. for their efforts. In 1624, they received a 'reward' of 10s., but on this occasion, so "…they should not playe."

It may seem odd that they received twice as much money for not playing as they did for playing, so why were the players not allowed to perform?

Prof Ted McGee, from the Records of Early English Drama says: “Poverty, the plague, dubious licences, or past experience with insolent actors were the grounds that other towns sometimes gave for paying players not to play.

“In the case of Bridport however, as for many other places, the rise of a Puritan faction in the town was probably what prevented them from performing in 1624. We know of this faction because of another performance recorded in a Star Chamber case - the performance in 1614 of two allegedly libellous songs that mocked the reformist Protestants of Bridport, a group that included some of its leading families, for hiding their vindictiveness and promiscuity under a veil of piety and religious observances.

“When such Puritans were in the ascendancy in local government, troupes such as the King's men might well have been paid a stipend so that their royal patron would not be offended and the town would be rid of the players and their ungodly plays.”

So, in 1624 Shakespeare’s premier acting troupe, left Bridport having been paid not to perform – most likely by Puritans who still paid so as not to upset their royal sponsor, King James I, who died a year later.

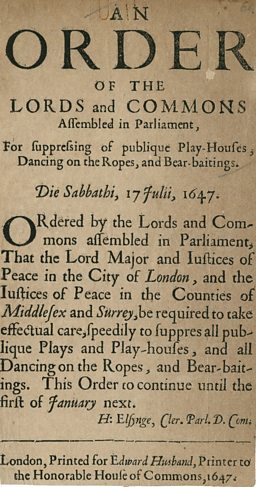

The Puritanical backlash against theatre

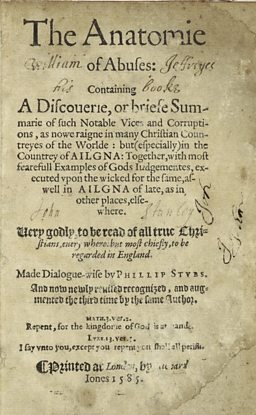

One of the most peppery of the Puritans in Elizabethan times is the pamphleteer Philip Stubbes.

Stubbes is perhaps best known for his popular book The Anatomie of Abuses (1583) in which he claims to expose some of the supposed ‘abuses’ in Elizabethan society and the theatre comes in for particular stick.

In Shakespeare and other dramas of the day it is the men who also play female parts. Stubbes and his supporters, known as anti-theatricalists, refer to men who dress up as women as “monsters of both kinds, half women, half men”. They consider such cross-dressing as a depravity.

Carrie Blais, commentating on the life of Philip Stubbes, writes: “Although stage cross-dressing was a necessity brought about by the all-male Elizabethan stage (women in England were barred from performing on the public stage until after 1660), critics have noted that Shakespeare’s use of cross-dressing is complex, and in fact may question the patriarchal structures of his time.

“Shakespeare attempts to undo the policing of gender boundaries and this attempt may perhaps be partly why the anti-theatricalists were so anxious about 'real' gender boundaries.”

Stubbes also argued that plays were magic. They had the power to turn men into aggressive beasts on stage – and that audiences might be drawn into the magic by imitating what they see.

Dismissing them as "filthy plays and bawdy interludes" Stubbes goes so far as to accuse them of being the work of the devil.

His work was a big success – it had four editions – clearly striking a chord with like-minded Puritans who also believed, like Stubbes, that "leisure leads to vice".

Shakespeare on Tour

From the moment they were written through to the present day, Shakespeare’s plays have continued to enthral and inspire audiences. They’ve been performed in venues big and small – including inns, private houses and emerging provincial theatres.

BBC English Regions is building a digital picture which tracks some of the many iconic moments across the country as we follow the ‘explosion’ in the performance of The Bard’s plays, from his own lifetime to recent times.

Drawing on fascinating new research from Records of Early English Drama (REED), plus the British Library's extensive collection of playbills, as well as expertise from De Montfort University and the Arts and Humanities Research Council, Shakespeare on Tour is a unique timeline of iconic moments of those performances, starting with his own troupe of actors, to highlights from more recent times. Listen out for stories on Shakespeare’s legacy on your BBC Local Radio station from Monday 21 March, 2016.

You never know - you might find evidence of Shakespeare’s footsteps close to home…

Craig Henderson, BBC English Regions

Who were the King's Men?

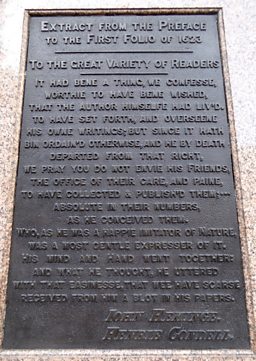

The King’s Men were the acting company to which Shakespeare was a member for most of his writing and acting career.

They were known as the Lord Chamberlain’s Men during the reign of Elizabeth I and become the King’s Men by the royal decree of King James I when he came to power in 1603.

In the royal patent of 1603, the King’s Men were named as – Lawrence Fletcher, William Shakespeare, Richard Burbage, Augustine Phillips, John Heminges, Henry Condell, William Sly, Robert Armin, Richard Cowley…”and the rest of their associates…”.

By the time of the troupe’s visit to Dorset, several of the actors named in the patent had already died. Lead actor Richard Burbage, who played Shakespeare’s demanding male parts – Richard III, Othello, King Lear, Antony and Macbeth – never retired from the stage and continued acting until his death in 1619.

Related Links

Shakespeare on Tour: Around the Solent

-

![]()

Ira Aldridge visits Southampton

The first black Shakespearean actor Ira Aldridge performing in the role of Othello

-

![]()

Portsmouth hosts Hamlet performance

Audience enjoy Hamlet in Naval Portsmouth as war rages over American Independence

-

![]()

Shakespeare's men perform before the King at Wilton in Salisbury

A royal audience in Salisbury

-

![]()

Shakespeare and Hampshire - where his footprints are lost in time

Is there any written evidence linking Shakespeare to Southampton?

Shakespeare on Tour: Around the country

-

![]()

Lancaster Theatre sparkles with Shakespearean talent

The Grand Theatre in Lancaster, which was once managed by Stephen Kemble

-

![]()

Reading’s Puritans turn away Shakespeare

Shakespeare's men paid not to play in Reading

-

![]()

Belvoir Castle

Belvoir Castle, home of the Duke of Rutland

-

![]()

Did Shakespeare visit Bristol in 1597?

Civic accounts show a high amount of performances in Bath