Shakespeare and Hampshire - where his footprints are lost in time

The Bard’s footprints have disappeared from Hampshire as surely as if he had left them in the sand at the ocean’s edge.

Despite countless links between the playwright and the southern county, no evidence can be found that Shakespeare was ever in Southampton or even Hampshire.

-

![]()

Much ado near me

Hear more Shakespeare stories on BBC Radio Solent

-

![]()

Shakespeare Festival 2016

The BBC celebrates the genius of the bard

There are so many links between Shakespeare and Hampshire.

We know he or his actors would have travelled through Hampshire on a South West tour. Academics believe the Earl of Southampton to be Shakespeare’s patron and certainly we know his acting company, The King’s Men, performed in Winchester.

Beyond that, what’s missing is written evidence to support the assertions – as our academic from the Records of Early English Drama (to his obvious frustration!) explains:

The soldiers who massed in Hampshire and boarded ships at Southampton for the D-Day invasion took inspiration from Shakespeare’s Henry V, in which an earlier invading force sailed from Southampton on their way to triumph at Agincourt. Southampton was also the title of Henry Wriothesley, Earl of Southampton, who is believed to have been Shakespeare’s patron. Yet no trace exists of Shakespeare’s having visited the port or the earl’s country house near Titchfield, nor indeed anywhere in Hampshire, largely because the relevant manuscripts have not survived.

The account books of Southampton’s mayors and stewards, which record performers’ visits to the city as early as 1428, have not survived for the years in the late 1590s and early 1600s when Shakespeare might have visited the town as a member of the Lord Chamberlain’s Men or King’s Men. In 1605-6, for example, The King’s Men traveled west from London at least as far as Barnstaple in Devon, and Southampton almost always featured in such tours to the southwest.

Similarly, no accounts or letters have survived that would place Shakespeare at the Earl of Southampton’s Hampshire residence. We do know from a letter to Henry Wriothesley’s grandfather, Thomas, the first Earl of Southampton, that Thomas’ wife and household celebrated with ‘Cristmas pleys and maskes’ at Place House, in 1537-38, shortly after Wriothesley obtained the former Titchfield Abbey from Henry VIII (The National Archives). Henry, the third earl, no doubt enjoyed performances at court by Shakespeare and his fellows, but we will never know whether they visited him at his Hampshire house.

Account records covering Shakespeare’s active years do survive from Winchester, and the city usually enjoyed one or two visits annually by the players of the Queen, Princess Elizabeth or the Prince Palatine, but The King’s Men did not visit Winchester until 1619-20, three or four years after Shakespeare’s death.

Shakespeare’s work is full of contemplation of the effects of time, and he might well have been standing on the Hampshire coast when he composed these lines from Sonnet 64:

When I have seen the hungry ocean gain

Advantage on the kingdom of the shore,

And the firm soil win of the wat'ry main,

Increasing store with loss, and loss with store,

Ruin hath taught me thus to ruminate,

That Time will come and take my love away.

The Bard’s footprints have disappeared from Hampshire as surely as if he had left them in the sand at the ocean’s edge. In Sonnet 65 he asserts that ink and paper will preserve his love—‘in black ink my love may still shine bright’—but in Hampshire even ink and paper failed him.

By Peter Greenfield, REED editor of Gloucestershire and Hampshire

Shakespeare's southern patron: An effeminate inspiration behind the bard's sonnets?

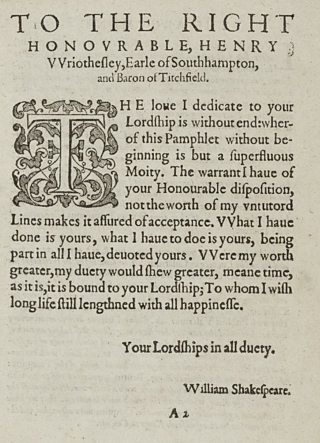

In 1593 William Shakespeare dedicated his narrative poem Venus and Adonis to the 3rd Earl of Southampton, Henry Wriothesley, and then in 1594 likewise with The Rape of Lucrece (pictured).

The Earl lived on the family estate at Titchfield Abbey near Fareham. He was Shakespeare’s chosen patron after arriving on the scene in London and a leading candidate for being ‘the fair youth’ in Shakespeare’s sonnets.

His connection with Shakespeare was reportedly forged as a result of his mother commissioning the Bard to write seventeen poems for her son’s 17th birthday.

The dedication to The Rape of Lucrece is couched in extravagant terms: 'The love I dedicate to your lordship is without end ... What I have done is yours; what I have to do is yours; being part in all I have, devoted yours'.

Although there is no lasting written evidence of Shakespeare or his players having performed at the Earl of Southampton’s Hampshire residence, the connection between the two is without doubt.

Some have conjectured that there was a sexual attraction, or relationship even – others that the language was all a part of the language of the day.

A recent piece in the Guardian newspaper claimed that a newly identified portrait of the young earl, looking highly effeminate, was sure to ignite a debate about the playwright’s sexuality.

Shakespeare on Tour

From the moment they were written through to the present day, Shakespeare’s plays have continued to enthral and inspire audiences. They’ve been performed in venues big and small – including inns, private houses and emerging provincial theatres.

BBC English Regions is building a digital picture which tracks some of the many iconic moments across the country as we follow the ‘explosion’ in the performance of The Bard’s plays, from his own lifetime to recent times.

Drawing on fascinating new research from Records of Early English Drama (REED), plus the British Library's extensive collection of playbills, as well as expertise from De Montfort University and the Arts and Humanities Research Council, Shakespeare on Tour is a unique timeline of iconic moments of those performances, starting with his own troupe of actors, to highlights from more recent times. Listen out for stories on Shakespeare’s legacy on your BBC Local Radio station from Monday 21 March, 2016.

You never know - you might find evidence of Shakespeare’s footsteps close to home…

Craig Henderson, BBC English Regions

Did Shakespeare’s acting company perform in Southampton – and if so, where?

We know The King's Men did tour to the South West at least once during Shakespeare’s own lifetime and Southampton was a usual stop on such a tour. Southampton was typically part of an itinerary that would follow the south coast, going on to perhaps Poole, Dorchester, Lyme Regis, Exeter, and even Plymouth before swinging north to Barnstaple, then back along the north coast of Devon and the Bristol Channel to Bristol.

From where a long tour might continue north up the Severn Valley, sometimes as far north as Carlisle before returning to London; or simply turn east from Bristol to Bath and back to London.

Although Southampton’s Bargate appears from historical records to have been the destination for generations of playing troupes, possibly including Shakespeare’s, the few documents which survive can suggest they weren’t entirely popular with the officials.

The records show a number of incidents where the local officials appear to blame the ‘players’ for causing damage – whether it be to tables, seating…you name it!

Peter Greenfield, Editor for the Records of Early English Drama, cites lots of evidence, and picks up the story here: “Southampton ordinances of the 1620s prohibit plays in the town hall, due to damage to the roof, and even to the tables and benches used by the mayor and bailiffs in the courts held there. In 1620 Southampton’s court ‘leet’ ordered that:

the table benches and seates ought to be amended by the Ioyner or Carpenter and the greate table to be new Covered with Clothe, The spoyle therof is Cheifelie occasioned by the sufferinge of Stage players to acte their enterludes ther, which draweth greate Concourse of disordered people bothe by daie and nighte: Be it therfore ordered That hereafter yf anie suche staige or poppett plaiers must be admitted in this towne That they provide their places for their representatcions in their Innes or else where they can best provide But euer be debarred for vseinge the like in the Towne hall (Southampton City Archives: SC6/1/37, fo.16v).

Despite this order it is apparent it hasn’t worked. Another prohibition issued three years later shows that players were still performing in the hall, so a ban was imposed:

…It is herefore ordered by generall Consent that from hensforth noe leave shall bee graunted to any Stage players or Interlude players or to any other person or persons resortinge to this Towne to Act shewe or represent any manner of Interludes or playes or any other sportes or pastymes whatsoever in the said hall.

At Southampton, the ‘towne hall’ refers to the hall over the Bargate. Two fifteenth century records refer to it as the town hall or guildhall, and none of the other halls in the town is referred to in this way. The space was far smaller than the Globe; indeed, the entire room might have fit on the Globe stage, yet acting companies of ten to fifteen members played there, presumably to an audience that at least outnumbered the players.

Related Links

Shakespeare and the 3rd Earl of Southampton

Shakespeare and the Third Earl of Southampton

Shakespeare dedicated two of his works to his patron, Henry Wriothesley.

Shakespeare on Tour: Around the Solent

-

![]()

Shakespeare's flagship acting company comes to Bridport

However the company were then turned away in 1624

-

![]()

Ira Aldridge visits Southampton

The first black Shakespearean actor Ira Aldridge performing in the role of Othello

-

![]()

Portsmouth hosts Hamlet performance

Audience enjoy Hamlet in Naval Portsmouth as war rages over American Independence

-

![]()

Shakespeare's men perform before the King at Wilton in Salisbury

A royal audience in Salisbury

Shakespeare on Tour: Around the country

-

![]()

Lancaster Theatre sparkles with Shakespearean talent

The Grand Theatre in Lancaster, which was once managed by Stephen Kemble

-

![]()

Reading’s Puritans turn away Shakespeare

Shakespeare's men paid not to play in Reading

-

![]()

Belvoir Castle

Belvoir Castle, home of the Duke of Rutland

-

![]()

Did Shakespeare visit Bristol in 1597?

Civic accounts show a high amount of performances in Bath