Monet for nothing: How Paul Durand-Ruel risked it all for Impressionism

4 March 2015

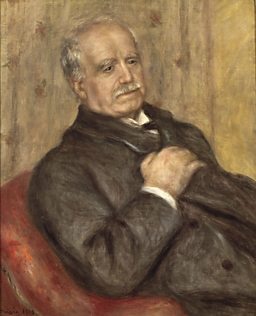

Lauded as the man who invented Impressionism, Paul Durand-Ruel was the art dealer who bought the works of Monet, Pissarro, and Renoir while they were still being ignored or ridiculed. Now the focus of a major exhibition at The National Gallery in London, WILLIAM COOK writes about how much the art world owes to Durand-Ruel’s passion and support for these artists.

In 1870 the French art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel fled from Paris to London, to escape the chaos and carnage of the Franco-Prussian War. In London he met two fellow refugees, Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro.

It was the start of an unlikely partnership which opened the door to modern art.

Durand-Ruel was a conservative, a monarchist and a devout Catholic, but he fell in love with Monet and Pissarro’s radical approach to painting. He adored their love of light, their emphasis on atmosphere and emotion.

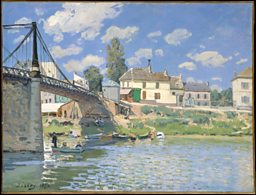

He started buying up their work, and the work of their contemporaries. Over the next 50 years he bought over 1000 Monets, around 800 Pissarros, about 1500 Renoirs, and hundreds of works by Degas, Sisley and Manet. He mounted exhibitions in Paris, London and America.

Thanks to Durand-Ruel, these ‘Impressionists’ (as myopic art critics called them, disparagingly) were able to make a living. As Monet said, ‘without him, we wouldn’t have survived.’

Inventing Impressionism is a sumptuous display of some of the many pictures Durand-Ruel bought and sold, but most of all it’s a tribute to the man himself. Through meticulous reconstructions of his most influential exhibitions, it shows how he popularised modern art, and became the first modern art dealer in the process.

The first room is a replica of his Paris apartment, decorated with floral murals by Monet, and Renoir’s tender portraits of his five children (Durand-Ruel’s wife died aged 29, when he was 40 - he never remarried). This apartment doubled as a showroom.

Visitors were reassured to see these daring paintings in such respectable surroundings. Durand-Ruel didn’t want to shock his customers. He set out to soothe them. He promised to buy back a painting if a buyer had second thoughts.

Despite his talent as a salesman, backing the Impressionists almost ruined him. He borrowed heavily to buy up all their works, and pay them regular salaries, but his passion for their paintings wasn’t always conducive to good business (he sold Renoir’s Girl With A Cat but missed it so much he bought back again).

“I never liked what sold, and what I liked I never managed to sell,” he recalled. “My best clients began to question me: ‘How can you praise these pictures, in which there is not a shred of quality?’.”

Durand-Ruel refused to give up and gradually the tide began to turn. In 1876, he mounted a big ensemble exhibition in Paris. It was savaged by the press. “They used to write, ‘These people are mad, but there is someone madder than them – the dealer who buys their work’,” remembered Monet.

But Durand-Ruel was smart enough to realise the publicity value of such controversy. In spite of these hostile reviews (or perhaps in part because of them) people flocked to see the show.

In his own way, Durand-Ruel was just as innovative as his artists. In 1883, he encouraged Monet to stage a solo retrospective – an unusual and audacious move for a living artist in those days. Again, the show attracted lots of interest, but buyers remained in short supply.

Then in 1886, Durand-Ruel was invited to exhibit in the USA. Once more, he was on the verge of bankruptcy. The Americans saved the day. “Without America, I would have been lost,” he recollected. “The Americans don’t criticise – they buy.”

Even after he returned to Paris, American collectors came to Europe to seek him out. Having bought in bulk, he could now control the market. “At last the Impressionist Masters triumphed,” he wrote. “My madness had been wisdom.”

In 1896, Berlin’s Nationalgalerie became the first public institution to buy an Impressionist painting (The Mill on the Couleuvre near Pontoise by Cezanne). Ironically, French museums lagged way behind. It wasn’t until 1901 that a French museum, the Musee des Beaux-Arts in Lyon (not Paris), finally bought an Impressionist – Woman Playing A Guitar by Renoir.

Fittingly, this stimulating exhibition culminates in a (partial) reconstruction of Durand-Ruel’s spectacular display at London’s Grafton Galleries in 1905 - still commonly (and quite rightly) regarded as the greatest Impressionist show of all time. It featured 315 works, including 196 from his private collection. Only 13 pictures sold, all to foreign buyers, but it put Impressionism on the map.

“The history of Impressionism Durand-Ruel tells in that 1905 exhibition, with these artists, is still, by and large, the one we follow today,” says Christopher Riopelle, co-curator of this exhibition. “Very few artists have entered the Impressionist canon whom Durand-Ruel didn’t champion.”

In 1905 the Sunday Times art critic, Frank Rutter, started a campaign to buy an Impressionist painting for the nation. Contributions flooded in. Rutter wanted to buy Monet’s Lavacourt under Snow (one of the highlights of the Grafton show) but the National Gallery didn’t want a Monet, or any picture sold by Durand-Ruel.

They spent Rutter’s money on a tamer painting, The Entrance to Trouville Harbour, by Eugene Bodin, who wasn’t represented by Durand-Ruel (and was also safely dead). Lavacourt under Snow was bought by the Irish collector Hugh Lane. When Lane died in 1915 (he went down with the Lusitania) he left this Impressionist masterpiece, and many more, to the National. Lavacourt under Snow is still hanging here today.

So did Durand-Ruel ‘invent’ Impressionism? Not quite, but it would have been very different without him. These painters were already painting in a new way before he met them, but without his tireless, skilful support, this revolution might well have petered out.

He transformed Impressionism into an international phenomenon. His influence is beyond measure. Nearly a century since he died, in 1922, aged 90, almost anything we call ‘modern art’ can be traced back to the Impressionists – and Paul Durand-Ruel.

Inventing Impressionism is at The National Gallery, London, from 4 March until 31 May 2015.

-

![]()

Inventing Impressionism: Exhibition gallery

More highlights from The National Gallery's exhibition of 85 artworks, devoted to the man who invented Impressionism, Paul Durand-Ruel.

Find out more

Art and Artists: Highlights

-

![]()

Ai Weiwei at the RA

The refugee artist with worldwide status comes to London's Royal Academy

-

![]()

BBC Four Goes Pop!

A week-long celebration of Pop Art across BBC Four, radio and online

-

![]()

Bernat Klein and Kwang Young Chun

Edinburgh’s Dovecot Gallery is hosting two major exhibitions as part of the 2015 Edinburgh Art Festival

-

![]()

Shooting stars: Lost photographs of Audrey Hepburn

An astounding photographic collection by 'Speedy George' Douglas

-

![]()

Meccano for grown-ups: Anthony Caro in Yorkshire

A sculptural mystery tour which takes in several of Britain’s finest galleries

-

![]()

The mysterious world of MC Escher

Just who was the man behind some of the most memorable artworks of the last century?

-

![]()

Crisis, conflict... and coffee

The extraordinary work of award-winning American photojournalist Steve McCurry

-

![]()

Barbara Hepworth: A landscape of her own

A major Tate retrospective of the British sculptor, and the dedicated museums in Yorkshire and Cornwall

Art and Artists

-

![]()

Homepage

The latest art and artist features, news stories, events and more from BBC Arts

-

![]()

A-Z of features

From Ackroyd and Blake to Warhol and Watt. Explore our Art and Artists features.

-

![]()

Video collection

From old Masters to modern art. Find clips of the important artists and their work