Utopia

Marking the 500th anniversary of Thomas More's book on the subject, poetry, prose and music on the theme of utopia, with readings by Nancy Carroll and Philip Franks.

Nancy Carroll and Philip Franks read poetry and prose inspired by Utopia as part of Radio 3's focus on the 500th anniversary of Thomas More’s book with music by Gluck, Richard Strauss, Parry, Dittersdorf, Shostakovich, Gilbert and Sullivan and Annie Lennox. The programme has been curated by New Generation Thinker Professor Nandini Das from The University of Liverpool.

Scroll down the webpage for more information about the music used, and Curator's and Producer's Notes.

You can also hear a Free Thinking debate on Utopia: Anne McElvoy chairs a discussion at LSE in which Professor Justin Champion, Dr John Guy, Politicians Kwasi Kwarteng and Gisela Stuart discuss Is politics about building a better world, or simply the art of the possible? This will be broadcast at 10pm Thursday 18th February.

Scroll down the webpage for more information about the music used, and the Producer's Notes.

Producer: Philippa Ritchie

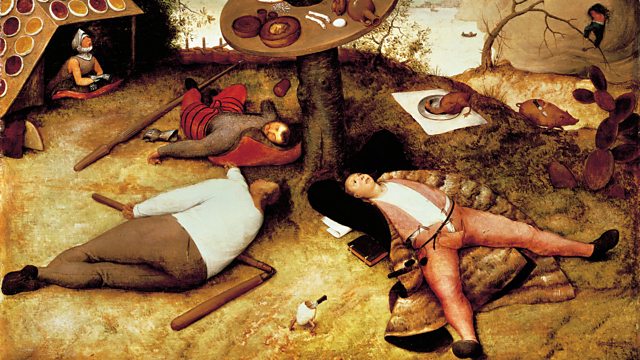

Main image: Land of Cockaigne, 1567, by Pieter Brueghel the Elder (1525 - 1569), oil on panel (credit Dea Picture Library)

Last on

Music Played

Timings (where shown) are from the start of the programme in hours and minutes

-

![]() 00:00

00:00Christoph Willibald Gluck

The Elysian Fields (Dance of the Blessed Spirits) from Orfeo ed Euridice

Performer: The Academy of St. Martin-in-the-Fields, Neville Marriner (conductor).- EMI CDC7470272.

- Tr9.

-

Ovid, translated by Ted Hughes

Metamorphoses, read by Philip Franks

![]() 00:05

00:05Ravi Shankar/Traditional Raga

Concerto for Sitar & Orchestra IV. Raga Manj Khamaj

Performer: Ravi Shankar & London Symphony Orchestra, Andre Previn (conductor).- EMI CDM7691212.

- Tr4.

Valmiki

The Ramayana, Book VI, Canto 116, read by Nancy Carroll

![]() 00:08

00:08Giuseppe Verdi

Messa Da Requiem No. 2 (coro) Dies Irae

Performer: Chicago Symphony Chorus and Orchestra, Daniel Barenboim (conductor).- ERATO 4509963572.

- CD1 Tr2.

John Milton

Paradise Lost, Book I, read by Philip Franks

![]() 00:10

00:10Edward Elgar

The Dream of Gerontius, Op.38 - 1. Prelude

Performer: London Symphony Orchestra, Richard Hickox (conductor).- CHANDOS CHAN86412.

- CD1 Tr1.

![]() 00:12

00:12Ray Russell

Initiation (Chinese flute)

Performer: Unknown.- MUM 150.

- Tr11.

Wang Wei

Peach Blossom Spring, read by Nancy Carroll

![]() 00:16

00:16Harry “Haywire Mac” McClintock

Big Rock Candy Mountain

Performer: Harry “Haywire Mac” McClintock.- MERCURY 1700692.

- Tr2.

Unknown, mid- 14th century (possibly Friar Michael of Kildare)

The Land of Cockaygne, read by Philip Franks

![]() 00:18

00:18Hubert Hastings Parry

The Birds of Aristophanes (1883) 4. Waltz

Performer: BBC National Orchestra of Wales.- CHANDOS CHAN 10740.

- Tr10.

![]() 00:21

00:21Gilbert and Sullivan

In lazy languor

Performer: The DOyly Carte Opera Chorus, Rosalind Griffiths (solo) and The Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, Royston Nash (conductor).- LONDON 4368162.

- CD1 Tr3.

Thomas More

Utopia: Marriage Customs, read by Philip Franks

![]() 00:25

00:25Bedrich Smetana

from 'The Bartered Bride' 1. Overture

Performer: BBC Philharmonic, Gianandrea Noseda (conductor).- CHANDOS CHAN10518.

- Tr1.

Plato

The Republic, read by Philip Franks

![]() 00:28

00:28Unknown (from Ancient Greek fragments)

Pean. Papyrus Berlin 6870

Performer: Atrium Musicæ de Madrid.- HARMONIA MUNDI HM901015.

- Tr13.

Philip Sidney

The Defence of Poésie, read by Nancy Carroll

![]() 00:29

00:29Maurice Ravel

Ma mère L'Oye. 5 pièces enfantines V. Le Jardin Féerique

Performer: Netherlands Philharmonic Orchestra Amsterdam, Carlo Rizzi (conductor).- TACET 207.

- Tr6.

Jonathan Swift

Gullivers Travels, read by Philip Franks

![]() 00:34

00:34Percy Grainger

Country Gardens

Performer: BBC Philharmonic, Richard Hickox (conductor).- CHANDOS CHA9584.

- Tr9.

Thomas More

Utopia: Visit of the Ambassadors, read by Nancy Carroll

![]() 00:38

00:38George Frideric Handel

The Arrival of the Queen of Sheba

Performer: The Academy of St Martin-in-the-Fields, Neville Marriner (conductor).- EMI CDC7470272.

- Tr1.

Charlotte Perkins Gilman

Herland, read by Philip Franks

![]() 00:42

00:42Eurythmics & Aretha Franklin

Sisters Are Doin' It For Themselves

- RCA 82876748412.

- Tr9.

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels

The Communist Manifesto, read by Nancy Carroll

![]() 00:44

00:44Igor Stravinsky

Le Renard (March)

Performer: Robert Craft/ Instrumental Ensemble.- RR CD643/VA.

- CD3 Tr6.

![]() 00:45

00:45Sergey Prokofiev

Le pas Dacier Op. 41- Closing Scene

Performer: USSR Ministry of Culture Symphony Orchestra, Gennadi Rozhdestvensky (conductor).- OLYMPIA OCD 103.

- Tr11.

George Orwell

Nineteen Eighty-Four, read by Nancy Carroll

![]() 00:48

00:48Keith Leary, David Marsden

Suspended Terror

Performer: Unknown.- RSM060.

- Tr18.

![]() 00:49

00:49Arthur Bliss

The World in Ruins (Excerpt from film Things to Come)

Performer: London Symphony Orchestra, Arthur Bliss (conductor).- DUTTON LABORATORIES CDLXT2501.

- Tr15.

![]() 00:52

00:52Thomas Adès

Friends dont fear (Caliban)

Performer: Ian Bostridge.- EMI 6952342.

- CD1 Tr13.

![]() 00:54

00:54Jean Sibelius

The Tempest: Intrada, Berceuse

Performer: Gothenburg Symphony Orchestra, cond. Neeme Jarvi.- BIS CD448.

- Tr9.

William Shakespeare

The Tempest, Gonzalos speech Act II Sc.1, read by Philip Franks

![]() 00:55

00:55Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf

Aurea prima sata est aetas (The first age was gold) Larghetto from Sinfonia No.1 Les Quatre Ages du Monde

Performer: Prague Chamber Orchestra, Bohumil Gregor (conductor).- SUPRAPHON 1105792.

- CD1 Tr1.

William Shakespeare

The Tempest Act V Scene I (Miranda and Prospero), read by Nancy Carroll and Philip Franks

![]() 00:59

00:59Jean Sibelius

The Tempest: Miranda

Performer: Gothenburg Symphony Orchestra, cond. Neeme Jarvi.- BIS CD448.

- Tr18.

![]() 01:01

01:01L Clark, M Dennis

"Show Me The Way To Get Out Of This World ('Cause That's Where Everything Is)"

Performer: Peggy Lee.- CAPITOL CDP7931952 1.

- Tr25.

Lucian of Samosata (2nd century AD)

A True Story, read by Philip Franks

![]() 01:05

01:05Jacques Offenbach

Le voyage dans la Lune A.631 - Overture

Performer: Philharmonia Orchestra, Antonio de Almeida (conductor).- PHILIPS 4220572.

- Tr1.

H.G. Wells

A Modern Utopia, read by Nancy Carroll

![]() 01:09

01:09Richard Strauss

Also Sprach Zarathustra, Nachtwanderlied (Song of the Night Wanderer)

Performer: Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, Herbert von Karajan (conductor).- DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 4158532.

- Tr9.

Curator's Notes: Utopia

Most cultures have some stories about golden worlds, even if they call them by different names – golden age, fortunate isle, peach blossom spring, Elysium, or Eden. They have one thing in common apart from the dream of perfect happiness that they present: we are always separated from them, not just by space, but by time, and often by life itself, when the ideal world happens to be the home of the virtuous dead. The earliest pieces we have in this programme are of this kind. There is Ovid’s description of the Golden Age, with its rivers of milk and nectar, its perfect glow progressively darkened by the ages of silver, brass and iron that followed. There is the description of Rama’s rule, a story that I grew up with as a child in India. It tells of an age of no wars, no illness, and no death, but the bit that I remember comes afterwards in the epic, when Rama has to sacrifice his wife to the demands of his people. There is the Chinese story of the Peach Blossom spring, first told by Tao Yuanming (365-427), which we have here in a later retelling by Wang Wei (699-759) – another perfect world inhabited by people of ancient names and clothes, a secluded enclosure that one can never find again if one is foolish enough to leave it behind. Most familiar, perhaps, is the Christian story of mankind’s greatest loss, the expulsion from Eden. However, even behind that exile there is the story of the very first loss of a perfect world – Satan’s rebellion and expulsion from Heaven, here in Milton’s powerful and deeply poignant version in Paradise Lost. Ideal places that are not set in the depths of time tend to be either purely conceptual, or blatantly fantastical. Plato’s Republic, a superbly rational social structure from which Socrates famously banished poets because of their ability to evoke irrational emotions is at one end of that spectrum. The anonymous thirteenth century poem about the Land of Cockaygne, with its cooperatively ready-roasted wildlife, is at the other. All of these have unattainability as a common factor. They are places of plenty, where sorrow and loss does not exist, where food is abundant, and pain is non-existent. They are perfect, but they are also always and already beyond our reach.

2016, however, marks the five hundredth anniversary of an important event, the historical moment when the ideal world came home to roost in the here and now. It was in 1516 that Thomas More, King Henry VIII’s scholarly, devout, sharp-tongued and frustratingly stubborn counsellor, published a slim Latin volume describing a ‘new island’. He called it Utopia. More’s story is different, because his ideal state co-exists with the rest of his contemporary world. It is described to a group of listeners – which includes a fictional version of More himself – by a man who supposedly accompanied Amerigo Vespucci on his historical fourth voyage to the New World and chanced on this island on his way home. So for the first time, in the middle of what sounds like an everyday, topical debate among a group of alert, intelligent, professional men about their contemporary Tudor England, its problems with law and order, and the economic disparities of its subjects, we have a superbly detailed description of an ideal commonwealth – its history and geographical setting, political structure, foreign relations, everyday life, family life, dining habits, religion, education, script, and a hundred other details. There is an abundance of food here as well, and peace, health, and order. In short, it has all those things we expect in an ideal world. The crucial thing, however, is that according to More’s narrator, it is all achievable.

As someone whose research is based on the great age of voyages and discoveries in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, I am fascinated by More’s book. It illuminates what is really exciting about an age when one discovery after another meant that on the one hand, suddenly an encounter with such a perfect land was entirely in the realm of the possible. On the other, such discoveries also constituted a wonderful license for the imagination, and that, after all, is what drives all utopian literature – our temptation to dream of something better, stronger, fairer, less fragile than the fallible world we occupy. About seventy years after More was beheaded in 1535 because he refused to acknowledge the annulment of Henry VIII’s marriage to Catherine of Aragon and his claim as the Supreme Head of the Church of England, Edmund Spenser would address Henry’s daughter, Queen Elizabeth I, to offer exactly that defence of the imagination’s right to dream of alternative worlds in his great poem, the Faerie Queene. I know that people will call this book an ‘abundance of an idle brain’, he writes, since no one knows ‘where is that happy land of Faery’. Yet new places are being discovered every day:

Who ever heard of th'Indian Peru?

Or who in venturous vessell measured

The Amazon huge river now found true?

Or fruitfullest Virginia who did ever view?Yet all these were, when no man did them know;

Yet have from wisest ages hidden beene:

And later times things more unknowne shall show.

Why then should witlesse man so much misweene

That nothing is, but that which he hath seene?Ever since the publication of the Utopia, writers have taken up the challenge of dreaming up new ideal worlds, and ‘Utopia’ has become a descriptive name for all of them. Poets and writers, as Philip Sidney argued in the sixteenth century, are best equipped to create such golden worlds, unencumbered by practical details and inconvenient truths; but they are also good at pointing out the risks and absurdities latent in all such dreams. That, too, is a characteristic of Utopian literature. There is no such thing as unquestionable perfection. One man’s idea of perfection is quite likely to be another’s idea of hell. More himself led the way in dissecting the world he had created, and I am rather fond of the slightly schoolboy-ish word-games he plays with his readers to signal that questioning. So his narrator, that original traveller to Utopia, is called Raphael Hythlodaeus: More’s educated contemporaries would know that the surname means ‘speaker of nonsense’. They would also notice that depending on the Greek roots you chose, the name of his ideal state could mean either ‘no (ou) place’ or ‘happy (eu) place’. The ‘More’ in the story admits that many things about ‘the manners and laws of that people … seemed very absurd’, and ends saying that ‘there are many things in the commonwealth of Utopia that I rather wish, than hope, to see followed in our governments’. It is never quite clear how seriously one ought to take his Utopian society’s treatment of wealth, mercenary soldiers, or indeed, of social practices like naked first meetings of courting couples.

For the many writers who followed More, Utopian writing often became the vehicle of satire, critiquing or poking fun at their contemporary society under the guise of writing about supposedly perfect alternative places, or carrying the ambitions of one’s contemporary society to absurdity to reveal their ridiculousness. Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels (1726; 1735) is perhaps one of the most famous examples of this: as one of his predecessors, Bishop Joseph Hall, suggested in the title of his own work of fiction in 1605, writers always, to some extent, describe Mundus alter et idem (‘Another world and yet the same’). For many others, however, the very idea of a ‘perfect society’ has rung warning bells. Twentieth century dystopian literature is full of worlds that are perfect societies and states designed by other people, where the very things that have always fascinated Utopian writing – equality, justice, equitable distribution of wealth, privileges and emotions, the perfection of humankind – all return to haunt us. The difference between an idealistic manifesto of a world of equality where ‘the free development of each [would be] the condition for the free development of all’ as Marx and Engels asserted, and the nightmarish totalitarianism of Orwell’s 1984, in many ways, is the difference between Miranda’s wonder-struck cry in Shakespeare’s Tempest, ‘O brave new world!’, and Prospero’s superbly understated, wearily knowing reply, ‘Tis new to thee.’ Yet the temptation to dream of perfect worlds remains with us; from the fantasies of unbridled appetite concocted by Lucian of Samosata’s 2nd century True Story, to the visions of futuristic fiction, and of science itself, that go beyond our familiar earth to other planets and planetary systems, we have always carried stories of Utopia with us, and will continue to do so as long as we make stories.Nandini Das is a Radio 3 New Generation Thinker and Professor of English Literature at the University of Liverpool. She specialises on Renaissance theatre and popular fiction, and early English voyages and contact with other nations and cultures.

Devisor: Nandini Das

Producer's Notes: Utopia

Gluck’s shimmering evocation of Elysium from Orfeo ed Euridice begins the programme and ushers in Ovid’s description of The Age of Gold. We then move east to the perfect world presided over by the Hindu deity Rama, described by Valmiki in The Ramayana and to accompany it is the Rāga Mānj Khamāj, performed by Ravi Shankar together with the London Symphony Orchestra in 1971. This is an evening raga, a time for reflection and remembrance of loss perhaps, but also of continuation which makes it appropriate for dreams of ideal worlds that are always tinged with loss.

Milton’s great poem of loss is thrillingly read by Philip Franks and I’m grateful to him for his suggestion of the Dies Irae from Verdi’s Requiem as a terrifying musical prelude to Milton’s description of Satan’s expulsion from Heaven “hurled headlong flaming” by the Almighty.

One of the earliest descriptions of an Utopian world occurs in Aristophanes’ play The Birds, first performed in 414 BC, in which two men disillusioned by Athens persuades the world's birds to create a city in the sky to be named Nephelococcygia or Cloud Cuckoo Land. I have picked the delightful Waltz from Hubert Parry’s incidental music to the play to underscore the thirteenth century depiction of The Land of Cockaygne and its enticingly edible charms. Parry composed the music for a Cambridge University production of the play in 1883. The production was a great success and, interestingly, starred a young M.R. James.

Gilbert and Sullivan’s operetta Utopia Limited, performed in 1893, was the second to last of their collaborations and not as successful as the others, though Bernard Shaw said in his review that he enjoyed it more than any of the previous Savoy operas. I’ve used the pretty opening number, sung by the chorus of the D’Oyly Carte Opera Company in 1975.

In lazy languor--motionless,

We lie and dream of nothingness;

For visions come

From Poppydom

Direct at our command:

Or, delicate alternative,

In open idleness we live,

With lyre and lute

And silver flute,

The life of Lazyland.To accompany Sidney’s Defence of Poesie I have chosen Ravel’s Le Jardin Féérique. It is the final part of his suite Ma Mère l'Oye (Mother Goose) - cinq pièces enfantines. Whereas the other four pieces are inspired by specific fairy tales, the Fairy-tale Garden celebrates the triumph of the magical world and seemed a fitting illustration of Sidney’s view of poetry as transcending Nature.

Unfortunately many planned Utopias end up as dystopias. Prokofiev’s Pas d’Acier, or Leap of Steel was commissioned by Diaghilev for a ballet in celebration of the new Soviet Russia and was first performed in June 1927 in Paris, coming to London a month later. It aroused a chorus of indignation against “Bolshevik Music” and when it was first performed in America in 1931 one critic asked whether the ballet was “propaganda or music”. Neither was the music welcome in the Soviet Union where Prokofiev was criticised for attempting to portray an image of Soviet life which he had not at first hand himself experienced. The recording I have used was performed by The USSR Ministry of Culture Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Gennadi Rozhdestvensky, who was awarded the title Hero of Socialist Labour in 1990.The British composer Arthur Bliss was commissioned in 1934 to compose the score for Things To Come, a science fiction film with a screenplay by H.G. Wells based on his short story of the same name. Wells was appalled by the final film, regarding it as a travesty of what he’d intended, but she score is today regarded by many critics as the first great British film score.

The programme ends with an extract from H.G. Wells’ 1905 novel A Modern Utopia in which he envisages a parallel world exactly like earth, but on another planet “out beyond Sirius” and differing from earth in that the inhabitants have created a perfect society. To accompany Nancy Carroll’s moving reading I have chosen an extract from Richard Strauss’s Thus Spake Zarathustra. Of course, this piece has become eternally associated with space travel after Kubrick’s use of its opening bars in his 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey. I have not used this, but rather the finale of the tone poem – The Song of the Night Wanderer, a transcendent piece of music that may almost make you believe in the possibility of Utopia.Philippa Ritchie, Producer

Broadcasts

- Sun 14 Feb 2016 17:30BBC Radio 3

- Tue 27 Dec 2016 16:30BBC Radio 3

Featured in...

![]()

Arts

Creativity, performance, debate

The hidden history of plant-based diets

Gallery