Understanding China through six characters

What can one lustful literary heroine teach us about China in the 1920s? What role would a kidnapped monk have to play in the future of Chinese chanting? And who were The Red Dragon’s first power couple?

In "Chinese Characters", historian Rana Mitter explores the country’s history through the remarkable lives of 20 key personalities. Here is a selection of those characters and their sensational stories.

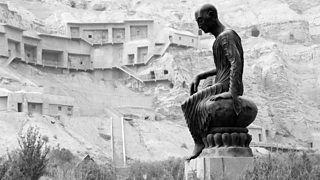

1. Kumarajiva – The translator monk

In today’s China, there are millions of Buddhists who chant Chinese phrases that were originally scribed in Sanskrit – all thanks to one monk.

Kumarajiva was born in 344 AD in the town of Kucha, a medieval centre of Buddhism. His mother yearned to become a wandering nun and hit the road with seven-year-old Kumarajiva in tow. It was on their travels that he learned the great Buddhist religious verses and how to chant them. As an adult, he embarked on a quiet life as a priest but it wasn’t to be – Kumarajiva was kidnapped (twice!) and ended up in the great city of Chang'an (modern Xi'an).

It was there that the emperor gave him the task of translating key Buddhist teachings – over two million Chinese characters’ worth – into a form that Chinese worshippers could understand and use. Although the monk himself thought translating from Sanskrit to Chinese was “like giving rice to people after chewing it”, by translating The Diamond Sutra, Kumarajiva created one of the most important pieces of religious writing in Chinese history.

Though not many Chinese Buddhists even know who he was, Kumarajiva’s smooth and fluent translations changed an entire religious culture and were essential to the Buddhist tradition that has lasted more than 1500 years.

2. Sima Qian – The grand historian

Anyone who produces a work of history in China “does it in the shadow of one writer”, says Rana Mitter – Sima Qian.

Sima Qian was a court official whose writing was distinctive in its objectivity – a quality that didn’t serve him well in his public life. He spoke up for a defeated general who was being heavily criticised by the emperor – the punishment for which was death. Luckily, there was the option of paying a large fine instead; unfortunately, Sima Qian didn’t have a penny. The only alternative was a painful and humiliating one – castration. “The worst punishment of all,” Sima Qian said.

After the event, having lost his confidence in court (unsurprisingly), he dedicated his life to chronicling history and produced the epic Shi Ji (Records of the Grand Historian). Running to 130 chapters and more than half a million characters long, it was a project of ambition that had never before been seen in China. But it was its attitude to history that made it truly unique. It included histories for subjects like music and biographies of lower officials, adventurers and merchants; and Sima Qian also pioneered oral history by interviewing participants. He even inserted his own dialogue and moral judgments. “He introduced nuance and breadth, creating a type of history that had a three-dimensionality previous accounts had lacked,” Rana Mitter states.

Sima Qian told the history of China in a way nobody had done before and influenced the way it was to be recorded for thousands of years to come.

3. Ding Ling – The feminist author

“I can’t control the surges of wild emotion, and I lie on this bed of nails of passion, which drive themselves in to me, whichever way I turn.” These are the words of Sophie, the most famous literary creation of, in Rana Mitter’s words, “the most famous female writer of 20th century China” – Ding Ling.

Ding Ling was born in 1904 and – a portent of her rebellious life to come – fled as a teenager to Shanghai to avoid an arranged marriage. The city was a hub for radical, liberal, feminist ideas, and Ding Ling became embedded in the left-wing literary scene. In 1927 she published “the Diary of Miss Sophie” in which the protagonist despises her “Steady Eddy” husband and lusts after a man she can’t have. It became a literary sensation, reflecting a wider shift in culture: the binding of women’s feet was coming to an end, women were going to work, and people were rethinking life and love.

However, the good times were not to last. Like many young intellectuals who joined the Chinese Communist Party, Ding Ling’s husband was executed and the author forced to flee. Ding Ling was criticised by Mao for a “bourgeois interest in individualistic feminism” and was sent into internal exile for two decades. It wasn’t until her last years that her work was officially approved once more.

Ding Ling isn’t well remembered in China but Sophie’s words present a potent message for China’s women, who still face issues of identity, sexuality and marginalisation today: “Live and die your own way.”

4. Chiang Kai-shek & Soong Meiling – The power couple

Before the Beckhams or the Obamas came, Chinese Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek and his wife Soong Meiling were Asia's first power couple.

Chiang Kai-shek led China in World War II, forming an alliance with two of the most powerful nations on earth – the UK and USA. In November 1943, the leader sat alongside FDR and Winston Churchill at one of the major conferences of the Second World War – making history as the first non-Western figurehead to do so. Madame Chiang is also in the photo, perched next to Churchill, which shows how significant she too was on the international stage. Chiang’s wife spoke fluent English after studying in the States, which meant, as Rana Mitter says, “she was his window to the world”. She spoke to both houses of Congress in Washington DC, only the second woman ever to do so, and was – if not joint leader – a powerful interpreter of China’s case to the rest of the world.

After the war, things went downhill. Chiang's government was weak and riddled with corruption, and his army was defeated by Mao's Communists in 1949. But China remains one of just five countries awarded a permanent seat on the UN Security Council for its record as a wartime ally. And for much of the 20th century, Chiang and Soong Meiling were the most prominent Asian politicians on the globe.

5. Confucius – The philosopher

In a competition for the most famous Chinese person in history, Confucius would surely win. The travelling philosopher’s ideas on how to live life in an ethical and practical way have informed China’s cultural DNA and identity.

Confucius’s elderly father died when he was young, leaving his impoverished mother to raise him. After studying Classics he joined the court, at a time of immense political turmoil – China was still 300 years away from having one ruling dynasty. The violent atmosphere led the young Confucius to think up ways that the country could be run successfully. He stressed the importance of rituals and rites in creating a stable and ordered world. Hierarchy was crucial: subjects should obey rulers, wives their husbands, and children their parents. (He was certainly no egalitarian!) Loyalty was crucial, harmony key, and this popular adage is one of his: “if you wouldn’t want something done to you, don’t do it to others.”

The smiling sage spent decades wandering between kingdoms, trying to convince them to adopt his ethical guide to ruling and living – but he didn't have much luck in his lifetime. Over the next few centuries, however, respect for his work – recorded on bamboo scrolls – grew and crystallised. For two thousand years, Confucian concepts would dominate Chinese statecraft and shape China.

His work still sits at the heart of modern China: the Communist Party make frequent references to Confucian ideas, books of his wisdom fly off the shelves and, as Rana Mitter says, ritual practice is “hardwired into the way the Chinese world works.”

More on China from Radio 4

-

![]()

Chinese Characters

Series of essays exploring Chinese history through the life stories of key personalities.

-

![]()

Intrigue: Murder in the Lucky Holiday Hotel

The story of the mysterious murder which changed the course of Chinese politics.

-

![]()

Empress Dowager Cixi: The Concubine Who Launched Modern China

Jung Chang's biography of the woman who single-handedly dragged China into modernity.

-

![]()

How Did China Ban Ivory?

The story of how China ended its love affair with white gold.