Televising the revolution: How Peter Watkins went to war

30 March 2016

In the mid-1960s two documentaries about war, directed by Peter Watkins, changed the face of British TV. Using an urgent, gritty TV news style and featuring amateur actors, Culloden ushered in the drama doc, while The War Game - described as "‘maybe the most important film ever made" - was initially cancelled by the BBC, following government intervention. With the distant Vietnam conflict being played out live on the news, Watkins made an 18th Century British battle and a future nuclear attack feel all too real. With the BFI releasing the films on on Blu-ray and DVD, WILLIAM COOK explores their enduring legacy and impact.

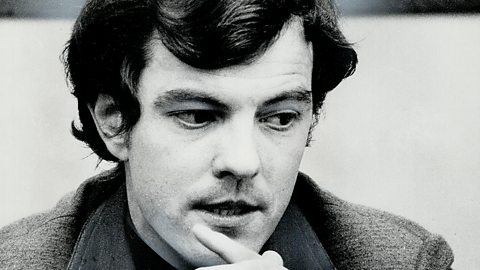

Half a century ago, a raw young filmmaker called Peter Watkins made two dramatised documentaries which revolutionised British television.

Culloden and The War Game were unlike anything that had been seen before. Mixing reportage and re-enactment, performed by untrained amateurs, these intensely naturalistic films still seem strange and shocking.

Watkins’ drama-documentary was like a news report from the front line

Peter Watkins was only in his mid-twenties, with only a few short films to his name, when he was hired by Huw Wheldon, the BBC’s dynamic Head of Documentaries.

Wheldon asked him what films he’d like to make.

The first two films on his list were The War Game - about the effect of a nuclear attack on Britain, and Culloden - about the last battle ever fought on British soil, in 1746.

Mindful that The War Game could be controversial, Wheldon asked him to make Culloden first. The result was a revelation.

In 1964, when Watkins made Culloden, historical films were staid and stuffy.

Watkins’ drama-documentary was like a news report from the front line. His shell-shocked soldiers spoke straight to camera. There were no patriotic heroes, only powerless victims.

The atrocities of the victors were portrayed with ruthless candour. Watkins made an ancient conflict between Jacobites and Hanoverians seem as topical as the Vietnam War that was all over the news at the time.

‘It was one of the first films to take a serious documentary subject and dramatise it,’ says Michael Bradsell, who edited Culloden.

‘There was even a kind of Peter Snow character, in 18th Century dress, crouching behind a wall with a telescope, reporting on the battle.’

For Bradsell, working with Watkins was a transformative experience.

‘So many of the BBC’s documentaries were worthy but rather unimaginative. They got the nickname “Talking Heads.” They might as well have been radio documentaries.’

Culloden was something completely new. ‘Peter was able to use people who had such arresting faces,’ says Michael. ‘He had a great eye for finding people who looked exactly right for the part.’

Danny Leigh on Peter Watkins

British Film Mavericks: Peter Watkins

Danny Leigh profiles a pioneer of docudrama who directed Culloden and The War Game.

The Jacobites' last stand

Extract from Culloden, 1964

Clip from Culloden, directed by Peter Watkins,1964. Clip courtesy of the BFI.

Culloden was a great success – British viewers had never seen anything like it – so Watkins was given the go-ahead to make The War Game.

The War Game is still frightening, even after fifty years

As Wheldon had anticipated, this was a highly sensitive subject.

The Cold War was at its height and the threat of nuclear attack had never been greater, yet the British Government’s official line was that such an attack would be survivable.

Any honest documentary was bound to blow this fallacy sky high.

The BBC’s Director General, Sir Hugh Greene, was against the project, as was the Chairman of the BBC’s Board of Governors, Lord Normanbrook (this was hardly surprising – Normanbrook had previously been Head of the Civil Service, with responsibility for Civil Defence).

The best that Wheldon could secure for Watkins was a process of ‘approval by stages.’

This was a pretty tepid endorsement, but thanks to Wheldon the film got made.

The War Game is still frightening, even after fifty years.

There was nothing fanciful about Watkins’ film – he simply leads us through the events which would surely follow a nuclear attack, from radiation sickness to civil unrest.

His research was meticulous, based on the nuclear attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

His matter-of-fact reportage was far more effective than Hollywood sensationalism, and his use of ‘ordinary’ people was incredibly realistic.

This was far closer to the truth than any government propaganda.

Lord Normanbrook decreed that the film should be seen by the government before it was broadcast.

The new Prime Minister, Harold Wilson, had just cut the Civil Defence budget. The last thing he wanted was a film revealing that British civilians would be helpless in the face of a nuclear attack.

The BBC announced that The War Game would not be televised. Sir Hugh Greene said it was ‘too horrific for the medium of broadcast.’

‘The government were very embarrassed about the way it portrayed their lack of readiness,’ says Bradsell, who also edited The War Game. ‘They did not want the public to start asking awkward questions.’

Surviving a nuclear blast

Extract from The War Game, 1965

Extract from The War Game, directed by Peter Watkins, 1965. Clip courtesy of the BFI.

Watkins was extremely upset. ‘You have finally betrayed me,’ he wrote, in a letter to the BBC. ‘God help anyone who tries to make a strong film within the BBC.’ Watkins resigned in protest. He never worked for the BBC again.

In 1985 it finally emerged that the government had persuaded the BBC not to broadcast

The BBC arranged a private screening at the BFI, and a limited cinema release. The critic Kenneth Tynan called it, ‘maybe the most important film ever made.’

Yet this selective distribution was no substitute for the mass exposure of TV.

‘We are always being told works of art cannot change the course of history,’ declared Tynan. ‘Given enough dissemination, I believe this one can.’

The War Game won an Oscar for Best Documentary at the 1966 Academy Awards, but the British Establishment made damn sure it was never given enough dissemination to change the course of history.

At the time, the BBC claimed this ban was their own decision.

In 1985 it finally emerged that the government had persuaded the BBC not to broadcast. The War Game was finally televised in 1985, twenty years too late.

Even without a TV screening, The War Game still made waves, inspiring John Lennon and Yoko Ono’s peace protests.

However the loss to British television was immense.

As Watkins said himself, ‘The War Game and Culloden are signposts to a direction that TV could have taken, but refused.’

Watkins has continued to make films, but though many of them have been critically acclaimed, none of them made the same impact.

‘It’s a great loss to the entire British film industry,’ says Michael Bradsell. ‘Those two films are enough to give him a major place in the history of filmmaking in this country.’

If The War Game had been broadcast in 1965, and Watkins had stayed at the BBC, who knows what else he might have achieved?

Culloden and The War Game are released together by the BFI, on Blu-ray and DVD, in a Dual Format Edition.

More from BBC Arts

-

![]()

Picasso’s ex-factor

Who are the six women who shaped his life and work?

-

![]()

Quiz: Picasso or pixel?

Can you separate the AI fakes from genuine paintings by Pablo Picasso?

-

![]()

Frida: Fiery, fierce and passionate

The extraordinary life of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, in her own words

-

![]()

Proms 2023: The best bits

From Yuja Wang to Northern Soul, handpicked stand-out moments from this year's Proms