The shell shock epidemic of WW1

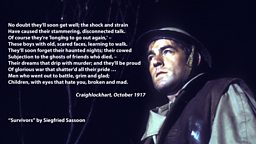

This week marks the 100 year anniversary of Wilfred Owen meeting Siegfried Sassoon at Craiglockhart Hospital. The poets met when being hospitalized for shell shock. The new series of Home Front explores the condition…

On 17 August 1917, the meeting of two traumatised soldiers at Craiglockhart Hospital near Edinburgh would come to define our image of “shell shock”. However, poets Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen were only two of 80,000 British troops officially suffering from this nebulous illness, which undoubtedly affected many, many more.

Though the term is believed to have originated in the trenches, “shell shock” is often attributed to military doctor Charles Samuel Myers in an article for the Lancet in February 1915. Looking at three case studies of soldiers displaying mysterious symptoms, including severe loss of memory and vision, Myers concluded “the close relation of these cases to those of "hysteria" appears fairly certain”.

By 1917 however, the medical establishment, including Myers himself, had largely abandoned the term favouring instead “war neurosis”. While doctors had previously thought the “neurasthenic” or “hysterical” symptoms they had observed were caused by a physical shaking of the brain, they began to realise that many sufferers had never actually been in shell explosion.

Around 40% of the casualties at the Battle of the Somme had shell shock. By the summer of 1917, with Passchendaele raging, the official rates were much lower and fewer soldiers were being brought back to Britain with the illness, Myers having recommended treatment as quickly - and close to the battlefield - as possible.

Nonetheless “shell shock” stuck amongst a populace desperate for a simple, alliterative phrase that would describe the sufferings of their loved ones. It therefore became, and continues to be, a metaphor for the far-reaching and tenacious trauma of the Great War, which continued to be felt long after the apparent end in November 1918.

“We could not understand the war madness that ran about everywhere” wrote Robert Graves after returning to Britain as a soldier, taking the line that “everyone was mad except ourselves”. The “we” included his comrade Sassoon, who in July 1917 caused outrage with his now famous statement “I believe that the war is being deliberately prolonged by those who have the power to end it”.

While his heroism at the front had earnt him both medals and the name “Mad Jack”, Sassoon’s anti-war declaration was dismissed in Parliament as the product of someone suffering “nervous shock and other mental ailments”. He was sent to Craiglockhart after Graves persuaded him to go before a medical board rather than a court martial for defiance. During this Graves himself, who would never be diagnosed with shell shock, broke down several times, weeping uncontrollably.

Treatment varied enormously; Sassoon and Owen’s experiences under Dr W H Rivers, a famously early follower of Freud, were not typical. Officers were generally given more sympathy than ordinary soldiers, who were often suspected of malingering and treated with “disciplinary” methods. Dismissing psychoanalysis as ineffective and impractical, medical officers Adrian and Yealland recommended using hypnosis, “suggestion”, “re-education”, and even “faradism” (electric shocks) on patients who had no sign of physical injury.

Those suffering from severe headaches, nightmares, nervous exhaustion, limb paralysis and an inability to speak were often recommended rest and outdoor recreation, often in rural isolation away from the civilian population. Specialist hospitals were set up around the country in places such as Netley, Maghull and Seale Hayne in Devon.

Military doctors with little or no knowledge of psychology were groping in the dark to find a lasting cure for this epidemic, which was seen to be a huge threat to the war effort. Though they were under pressure from the beleaguered British Army to get men well again for the front, few returned to combat for any length of time.

Around 40% of the casualties at the Battle of the Somme had shell shock. By the summer of 1917, with Passchendaele raging, the official rates were much lower and fewer soldiers were being brought back to Britain with the illness, Myers having recommended treatment as quickly - and close to the battlefield - as possible.

At this time, however, Germany’s strategic bombing campaign was reaching its height. The first Gotha aeroplane raid on Britain which took place in Folkestone on 25th May was soon followed by one on 13th June which killed 162 Londoners in broad daylight. A first-hand witness, Sassoon wrote that whilst such things were previously only seen in the trenches, now here “an invisible enemy sent destruction spinning down from a fine weather sky”.

It is no surprise then that the phrase “air raid shock” was beginning to gain currency, with the boundaries between the home and fighting front becoming increasingly blurred. At this particular moment, 100 years ago, the trauma of war seemed everywhere inescapable.

Home Front from BBC Radio 4

-

![]()

17 August 1917 - Adeline Lumley

Adeline and Victor Lumley both see clearly, but in different ways.

-

![]()

Home Front Story Explorer

An innovative new way to explore the characters, themes and storylines.

-

![]()

World War I

Discover how the people and places around you changed during WW1.

-

![]()

Home Front Podcasts

Drama serial tracking the fortunes of a group of characters on the home front.