Seven things you need to know about Alzheimer's disease

The world's biggest ever study on early signs of Alzheimer's disease is about to get underway. Involving eight UK universities, the Alzheimer's Society, and led by the University of Oxford, the Deep and Frequent Phenotyping Study, will carry out up to 50 tests on 250 volunteers to find subtle indicators of Alzheimer's many years before the more obvious symptoms develop. The World at One has been investigating.

Devastating diagnoses

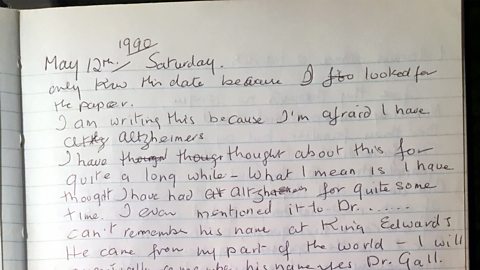

Cate Latto's mother Patricia has Alzheimer's disease. Cate found a diary written by her mother when she was in her 60's, more than 20 years before she was diagnosed with the disease. The diary is a striking indicator of how long Alzheimer's takes to develop.

Diary of an Alzheimer's sufferer

Patricia Latto kept a diary of her experience with the onset of Alzheimer's disease.

It's a disease which devastates families as loved ones deteriorate, sometimes losing all the characteristics which makes them the person they were. It's a sad, scary and sometimes apparently hopeless disease, which scientists are determined to overcome.

Here are seven important factors which researchers are considering in their combat against the tragic disease.

1. Time

Alzheimer's disease doesn't usually affect people until very late in life. But the disease starts to develop in the brain unseen much earlier than that. Scientists believe Alzheimer's is causing damage to the proteins in the brain for up to twenty years before symptoms like memory loss and confusion make it noticeable. But by then it is too late to do anything about it. None of the drugs or treatments have been shown to stop or delay the onset of Alzheimer's disease.

Alzheimer's is the most common form of dementia with 850,000 sufferers in the UK alone. It is estimated that one person develops dementia every three minutes and with the ageing population growing the numbers are expected to reach 2 million within 30 years.

2. Walking

Scientists are searching for better ways of spotting Alzheimer's disease earlier in life to enable a better chance of delaying or stopping its progress. One early sign could be the way you walk.

Tiny - almost imperceptible - changes to our pattern of walking could be a sign of problems developing deep within the brain.

Scientists know that walking does not only involve the parts of the brain responsible for movement, but also many of the higher functioning areas like the pre-frontal cortex, the parietal cortex and the hippocampus - vital for spatial memory.

"Think about your footsteps in the sand, and how even and well placed they are," says Professor Lynn Rochester from Newcastle University, "We're looking at very, very subtle changes in how those footsteps might start to appear."

Walking and Alzheimer's

Changes to our pattern of walking could be a sign of problems developing in the brain.

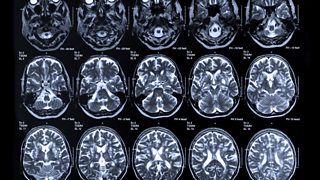

3. Brain Scans

Brain scans of people with more advanced Alzheimer's disease show clear damage to the brain. One of the first areas to be affected is often the hippocampus, deep within the brain, which is responsible for forming memories. Alzheimer's attacks the brain by causing proteins to make clumps, called amyloid plaques, and tangles which together block nerve cells, and spread to other parts of the brain, impairing language, understanding, facial recognition, movement and decision making.

Three types of brain scans are being used in the study to detect subtle changes in the brain much earlier. MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) scans reveal the physical structure of the brain and show any shrinking to areas such as the hippocampus. PET (Positron Emission Tomography) scans use radioactive markers to show the position of amyloid plaques. MEG (Magnetoencephalography) scans show brain activity by measuring tiny changes in the brain's magnetic field.

4. Drug Trials

Over the last twenty years research on the causes of Alzheimer's disease has been extraordinary. Much of the mechanism of how the disease develops in the brain is understood. Alongside this research there have been many promising drugs developed which seem to slow or stop the development of amyloid placques in the brain. The drugs work well in the labs, at a cellular level, and they seem to work in trials on animals. But again and again when these drugs are tested on people the medical trials fail because they do not show the progress promised. 99% of drugs trials have failed in the last ten years.

Scientists believe this is because the trials are being done on people who already show established signs of dementia, and by then the damage is too far advanced for the drugs to be effective.

Alzheimer's drug trials

Are Alzheimer's drug trials failing because of when they are conducted?

5. Big Data

Scientists are approaching the problem in an ambitious way. They are using every type of test they know which could be an indicator of Alzheimer's disease and combining them all in a way which will generate enormous amounts of clinical data. They will carry out frequent brain scans on participants, every one or two months; they will monitor their movement using wearable devices; they will give them memory tests and cognitive tests using apps on mobile phones and tablets. They'll carry out eye tests to detect changes to the retina. And they'll do blood tests, urine tests, and tests on spinal fluid.

Every MRI brain scan alone produces about 5-6GB of data, so together all this data will require enormous computing power to analyse. Scientists believe that by using big data analytics they will detect subtle changes revealing which tests, or combination of tests, best work to predict the very early development of Alzheimer's disease.

6. Ethics

Alzheimer's disease is often under-reported because people are sometimes unwilling or fearful of admitting they have it. Because there have been no successful treatments, the advice from doctors to people who do have Alzheimer's disease is limited to the sorts of suggestions which apply to almost anyone as they get older - eat a healthy diet, get plenty of exercise, and keep the brain active by engaging in as much social activity as possible.

So what do you tell someone you suspect might have very early signs of Alzheimer's? People taking part in scientific studies are not usually told if they are at risk of developing Alzheimer's. And the scientists conducting the studies do not know either. This is an important part of making sure the research is not influenced by knowledge of someone's medical condition. But if better ways are found of detecting early signs of Alzheimer's, should people at risk be told, when there is little they can offer to improve the prognosis? Scientists think there needs to be public consultation on this question.

Ethics of scientific studies

Cate Latto is taking part in an Alzheimer's Society study called Prevent because of her family history of Alzheimer's. She believes, on balance, that she would like to be told if she shows signs of the disease.

7. Cure?

The experts believe the best chance of finding a cure for Alzheimer's, or a way of delaying its development, is to find better ways of detecting it - years before the disease wreaks havoc in the brain. Early indicators could then be looked for as part of routine health screening, just like checks on blood pressure and blood tests.

Many drugs already developed show promise, and the continued development of more personalised, highly targeted drugs, is also important. The belief is that if these drugs are tested on people much earlier in the course of Alzheimer's disease, before they show the clear symptoms, the drugs will slow or even stop the further development of the disease.