When does noise become music?

By Tom Service

We like to think we can separate “noise” from “music”. Noise is everything that isn’t music when you’re at a gig, a concert, or an opera. It’s the clanking of the bar behind you right in the middle of your favourite ballad; it’s that mobile phone whose infuriating jingle goes off just as that Bruckner slow movement is reaching its climax; it’s that person who coughs just as Mimi is about to die in Puccini’s La bohème.

What’s all that noise?

Noise is also all of those sounds you’d really rather weren’t there in your daily life: the clanking of the truck that takes away the bins at 5am on a Monday morning, or the blare of jet engines as they descend into the airport. Man – I can’t concentrate on my piano practice with all this noise! And my ham-fisted piano-playing isn’t noise, by the way. If I choose to make these sounds, however terrible my playing of a Bach prelude, they’re not noise, but intentional consequences of my actions, and therefore, not noisy. But if you make them, it’s another story. Hang on a minute: maybe I’m just as noisy as everyone else...

Noise explained

What is noise?

Is noise just sound in the wrong place? Tom Service finds out.

So noise isn’t just a question of sound or music. It’s about society and politics, too. Over the centuries, as our societies –, especially our cities–, have become noisier and noisier, there’s been an ever-increasing clamour for all that noise to stop. The problem in the 18th century, as the author Emily Cockayne tells me, was that noise meant industry, which meant productivity, money, success. So if you stopped all the noise, you would have halted the industrial revolution in its tracks – bad news for metropolitan and technological progress.

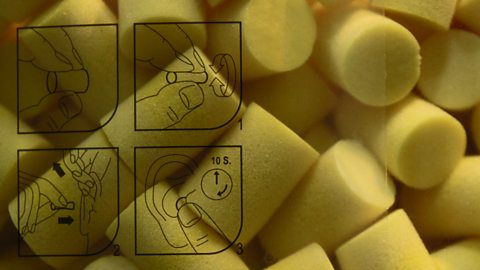

But that could have been good news for the countless millions of workers all over the world who, then and now, face lifelong injury to their hearing by working in heavy industry, in mining, or in factories. For those in charge, the noise of all that activity is about power and productivity, but for the workers themselves, it’s a potentially hearing- and even life-threatening problem.

And it’s not just in workshops or production lines. Orchestral musicians face similar dangers. One string player is suing his former employers for damaging his hearing after years spent playing Wagner, Verdi, and Puccini in the orchestral pit of an opera house. That’s an especially poignant example of how one person’s sonic manna from heaven – the raptures that we experience in the audience during all those operas – is another person’s health-damaging pain.

The artists of noise

So we live in a noisy world. And for musicians and composers, the decision is whether to use that noisy totality of the soundscape that’s around us all the time, or to ignore it. The first composers to insist on the aesthetic necessity of noise were the Italian Futurists at the start of the 20th century. Luigi Russolo and his fellow Futurists were the original artists of noise (their manifesto was called The Art of Noises), who made and performed with new noise-producing instruments. And in New York, Edgard Varèse (an essential influence on the young Frank Zappa) used sirens, alarms, wind-machines, and lion’s roars in his huge orchestral hymn to American modernity, Amériques.

When they seem to enter your body through every pore of your skin, you have no choice but to submit to them.

Varèse and the Futurists were predecessors of the 20th century’s most famous noise artist, John Cage, whose supposedly “silent piece”, 4’33’’ [Four minutes and 33 seconds], isn’t anything of the kind. Instead, 4’33’’ – first performed by a pianist who sat at a piano in 1952 and didn’t play a note – is a composition that invites us to tune in to the environmental sounds around us during a performance. Today, that might mean gentle hums of air-conditioning or the whistle of a hearing-aid loop, but it’s just as possible to create 4’33’’ in the most noisy places you can imagine, like the middle of a jet engine or a volcanic eruption. Cage’s essential point is that we should listen in to the noises of the world, rather than subtract ourselves – and our music — from them.

Forward-wind to the 21st century, and there’s a thriving international scene of noise artists, using extremes of white noise – massive sonic slabs of the kind of static sound you hear between radio or TV stations – and a whole gamut of electronic and acoustic sounds. And when you’re confronted by this music, it’s an astonishing and strange experience. Because in the middle of the noisy storm, there’s a strange sense of calm. At least, that’s what I found at an evening of noise music at Café Oto in London. When the noises are so loud, when they seem to enter your body through every pore of your skin, you have no choice but to submit to them, and you’re hardly conscious of yourself any more, since your body becomes simply a physical vessel for noise to pass through. I found a kind of transcendence in listening to noise in this way, as if the best way to find a respite from the noise in our daily lives is to go to the noisy source itself.

Why it matters

But there’s a more fundamental sense in which noise matters in all of our musical lives. And that’s because without noise, there would be no music.

Here’s what I mean: whenever you listen to any music — especially when it’s performed by acoustic instruments — there is always a halo of noise around any sound that you hear. Take a violinist playing the solo works of Bach: it’s not just the notes that are part of the way the music communicates _: we need to hear the friction of the bow hair on the string, the microsounds of their fingers on the fingerboard, the special resonance of the wood of that particular instrument, even the breathing of the player themselves. Take all of those “noises” away, and you would take away the music’s vital, human communication. And that’s true of the vast majority of musical experiences we all have.

We need to understand the social power of the noises we make, but we can’t and we mustn’t stop making them. No noise, no music, it’s that simple. In short: let’s make some noise!

More from The Listening Service

-

![]()

What's all that noise?

Tom investigates - when is noise just noise, and when is it music? is it just sound in the wrong place?

-

![]()

Why do we love repetitive music?

Our lives are ruled by repetition. Tom Service considers why we love repetition in music.

-

![]()

Share this page Music Intros that Make You Say 'Wow'

Three ways the beginning of a piece of music grabs our attention.

-

![]()

The Listening Service Playlist

Hear all of the music featured in the programme each week with BBC Music