Why I decided to get to know the man I killed

By Jonathan Izard, presenter of Radio 4's Meeting the Man I Killed

Five – the average number of people killed every day on Britain’s roads, according to the latest figures*. That’s an annual total of 1,792 fatalities.

It’s good news that the figure has come down from over 3,000 ten years ago. But for the individuals who died or for the families and friends whose lives were shattered by their loss, there is no good news.

A quarter of the people who die on our roads are pedestrians.

One of those pedestrians was a man called Michael Rawson. On New Year’s Eve in 2015, shortly after 5pm, Michael Rawson crossed the road in front of my car as I was driving on a country road in Norfolk. I didn’t see him until the second before the impact. It was too late. I hit him. He died.

“No time to respond. My car smashed into him”

In this clip, Jonathan Izard returns to where his car hit Michael Rawson.

Disbelief. Shock. Trauma. Grief. Horror. Sorrow. Regret. There are plenty of words that come close to describing part of the maelstrom of emotions I experienced after the accident, some of which continue as symptoms of PTSD.

Terror is another. Am I guilty of something? Was I texting, speeding? Had I been drinking? Was my car faulty in some way: the brakes? the lights? No, no and no.

This was not just a man who died; he was a man who lived

The police investigation took months. I was interviewed under caution and finally told their decision was not to recommend prosecution. But there was still an agonising wait of almost a year until I was able to attend the inquest and hear the calm voice of the coroner announce to a hushed court that “no blame should attach to the driver”.

“No,” people say, “don’t blame yourself; it wasn’t your fault.” But even if that’s true, it still happened. A man died after an impact with my vehicle. How do I make sense of that? How do I go on?

I am a different person now. His death is part of my history, part of my personality. I carry it with me, albeit skilfully disguised and invisible from view. Until now.

A year after the accident, legally absolved and free of the judicial process, I had an urge, inexplicable but impossible to ignore, to find out more about Michael Rawson.

Cautiously, wary of hostility, I approached his friends. With hardly any exception they were welcoming, kind and generous. I received empathy and compassion. They filled out the sketchy sense I had into a rounded character: a loveable rogue, a naughty iconoclast, someone with a restless energy and a hunger for life.

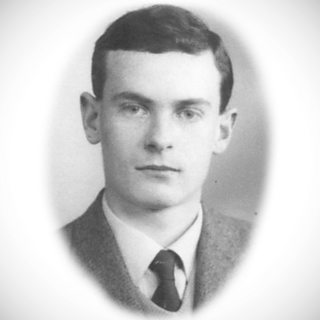

They showed me pictures of him and as I discovered more about him. Michael Rawson began to come – ironically – alive. He gradually became a man of pastimes and passions. He had delighted and infuriated his friends. He had a face and a voice. It was still a tragedy, an unnecessary death; still a statistic. But this was not just a man who died; he was a man who lived.

Michael Rawson seems a good man, a funny man. He was intelligent, cultured and had strong opinions. He was determined and liked to take risks. One of his friends told me Michael and I had things in common and would have enjoyed stimulating conversations. I wish our paths could have crossed in a different way.

And they might have. If only… If only I’d set off a minute earlier or a minute later, I wouldn’t have been in that place at that time. So many if-onlys and what-ifs. But none of those saved Michael Rawson then or can spare me the grim reality now of living with this new, unwanted identity: I am someone who has taken the life of another man.

“That could have been me,” we say. “That was a near miss.” We’ve all said it. For 44 years I loved driving and never had an accident. And then it was me. It wasn’t a near miss. It was a collision that resulted in one life lost and other lives shattered.

It’s not just me. With so many accidents on our roads, there must be hundreds, thousands, of others who have gone through something similar. Who are they? Where are they finding support? Who are they talking to?

One person I spoke to gave me advice: “Block it. Just block it.” I know that’s not the route to recovery for me. I am a psychotherapist but I also know the benefits of being a client. I’ve found that I’m good at asking for help; I was able to access first-class therapy.

And going public with this is an essential part of my ongoing healing. I have needed to acknowledge and name the wretchedness; not repress it but express it and process it. If I can facilitate that for others, what a privilege. I would like to be able to widen the conversation.

Even if you’re not someone who’s ever been involved in a road traffic accident, I also want you to learn from what’s happened to me – whether you drive, ride a motorbike or a bicycle, or are ever a pedestrian. Slow down. Take more care. Cross the road with full attention.

If I can discourage just one person on one occasion from taking an unnecessary risk, from having to hear the screech of brakes and the sickening crunch of collision, I have achieved something valuable.

Don’t become a road traffic statistic. Or someone traumatised by one. Have a safe journey, please.

*Source: Department of Transport, 2016

-

![]()

Meeting the Man I Killed

Listen to Jonathan Izard's documentary about trying to get to know Michael Rawson, the man he killed.

More from Seriously...

-

![]()

Five women who broke the glass ceiling

These remarkable women have made a real an impact on democracy in their countries.

-

![]()

Why is country music a hit in Nigeria?

Tayo Popoola travels to West Africa to find out.

-

![]()

Seven things you need to know about Antifa

What is the leftist movement that has been making headlines?

-

![]()

A plate of Peru

Try Martin Morales puka picante vegetariano recipe.

-

![]()

Five Things I Learnt from Wearing a Wig

What Brian Kernohan learnt about himself and our relationship to wigs.

-

![]()

Why are acid attacks on the rise?

Ayshea Buksh investigates the rise in UK attacks.

-

![]()

Five slogans to live your life by

Could we really live by our lives by the words of a slogan? Possibly not...

-

![]()

The death and rebirth of Zora Neale Hurston

Once forgotten, the author is now revered by Alice Walker and Solange Knowles.