Five mind-blowingly bonkers (and brilliant) early Soviet choral works

So you’ve heard Prokofiev’s enormous, barmy Cantata For The 20th Anniversary Of The October Revolution – replete with accordions, military band, cannons, air-raid sirens, and topped off with a speaker on megaphone playing the voice of Lenin, writes BBC producer Steven Rajam.

But it’s just… not enough for you. You crave more: bigger, louder, even more crackers examples of Soviet vocal maximalism; works that turn that choral dial right up to одиннадцать [eleven]!

Luckily for you, the early years of the USSR formed the perfect conditions for some of the most dazzlingly original – and occasionally frankly absurd – choral works of the 20th century. A generation of gifted young composers, a state that demanded vast vocal showpieces that set the words of its heroes, and an atmosphere – at the beginning at least – of wild experimentation…

Here’s my guide to five early Soviet-era choral experiences that pushed vocal and musical frontiers right to the limit…

1. Shostakovich – Symphony No. 2 (finale)

"A toe-curling poem in praise of Lenin..."

Shostakovich's Symphony No. 2, commissioned for the 10th anniversary of the Revolution.

By 1927, the 21-year-old Dmitri Shostakovich was the hottest property in Soviet music. The previous year, his First Symphony – written as a graduation piece from the Petrograd Conservatory – had wowed audiences and critics with its quicksilver, sardonic wit and elegant, neo-classical melodies.

It’s fair to say he didn’t play safe with the follow-up.

Shostakovich’s Second is surely one of the battiest symphonies of the 20th century: a long, atonal depiction of primordial chaos, followed in short order by a huge choral knees-up of a finale that bolts on, Frankenstein’s monster-style, a frankly toe-curling poem in praise of Lenin (sample: Oh, Lenin! You forged freedom through suffering / You forged freedom from our toil-hardened hands…)

Later in his life, Shostakovich would compose a bona fide choral symphonic masterpiece – his Thirteenth, subtitled “Babi Yar”, setting words by dissident poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko. But the Second has never enjoyed much popularity – often panned by Western critics as agitprop nonsense, while criticised by the Soviet authorities for being too avant-garde.

I think that’s a shame: because for sheer compositional chutzpah, there’s certainly nothing quite like it…

2. Nikolai Roslavets – Komsomoliya

When Igor Stravinsky was asked who he felt was the most interesting Russian composer of the 20th century, it’s fair to say he had a fair palette to choose from: Shostakovich, Rachmaninov, Scriabin, Prokofiev, even himself. Instead, he replied unhesitatingly: “Nikolai Roslavets”.

He had a point. Dubbed “the Russian Schoenberg”, Roslavets burned like a firework – penning a host of perfumed, almost atonal piano works in the second decade of the 20th century, before turning his attention to the promotion of Soviet ideology in the 1920s.

Komsomoliya is a rare foray for him into choral music – and what a foray. A wordless choir swirl and swoop around a breathlessly intense orchestral crescendo, reminiscent of the “machine music” of pieces like Mosolov’s “Iron Foundry”. Vocal effects, hollering, glissandi (slides) and sheer volume sweep over the listener like waves crashing into cliffs. Utterly unique, its fusion of stark propaganda and dazzling musical modernism predates Prokofiev’s more celebrated blend of the two in his October Revolution Cantata by a full decade.

Sadly, despite being a passionate political and musical revolutionary, things didn’t end well for Roslavets. A victim of the cultural purges of the early 1930s, he was forced to admit his “political mistakes” and packed off to Tashkent, Uzbekistan. Shortly after, he suffered the first of a series of debilitating strokes. By 1944, he was dead.

3. Ivan Wyschnegradsky – Choeurs

What do you do when the wild harmonic experiments of Scriabin and Roslavets just feel a bit too... mundane? How about inventing an entirely new musical system?

Like Prokofiev, Ivan Wyschnegradsky was a student of Rimsky-Korsakov at the St Petersburg Conservatory and a rising star of Russian music at the time of the Revolution. Like Prokofiev, he was to make his home in France in the tumult that followed.

But while Prokofiev was fast becoming the darling of 1920s Paris, Wyschnegradsky was busy in his new home tinkering with a bizarre new instrument: a piano that would give him extra notes in between the semitones of the conventional scale. (Don’t ask where the extra fingers to play them came from).

For the next half-century, he’d compose music in quarter-tones, sixth-tones, even twelfth-tones – making a dizzying 72 notes to the octave – producing an array of works that are bewilderingly difficult to perform, yet to my ears sound strange, otherworldly and wonderful (at least in small doses) – like hearing a warped LP playing at the wrong speed.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, his Choruses of 1926 for two quarter-tone pianos, choir and percussion have never been commercially recorded. Anyone out there fancy a challenge?

4. Prokofiev – Seven, They Are Seven

Prokofiev: Seven, They are Seven, Op. 30

Prokofiev's 1917 cantata was set to words by Konstantin Balmont.

Penning the words to one trippy Russian choral work is quite an accolade. Being the inspiration behind TWO extraordinary vocal flights of fancy – composed by perhaps the two greatest Russian composers of the early 20th century – just seems, well, greedy.

But that’s the achievement of the Symbolist poet Konstantin Balmont, who in 1911-12 supplied Igor Stravinsky with the woozy lyrics to his choral scena “The King Of The Stars”. Scored for a vast orchestra including two harps, eight horns and six-part male choir – yet lasting barely five minutes – it was praised by Debussy for its radical imagination, though the older composer advised Stravinsky he might find it a mite tricky to get performed…

But “King Of The Stars” predates the October Revolution, so I definitely can’t count it here, no matter how hallucinogenically weird it is, nor whisper that you definitely should go and seek it out...

Instead, why not give Balmont’s second great choral phantasmagoria a go? The cantata “Seven, They Are Seven” by Sergei Prokofiev was completed shortly after the October Revolution, just before the composer decided to try his luck in America. The work’s inspired by an ancient Middle Eastern exorcism, and has the feel of a surreal, infernal incantation – with hypnotic repetitions of the word “seven” and ominous rolls of the bass drum.

At seven (of course) minutes long, it’s only slightly longer than Stravinsky’s earlier Balmont setting. But never mind the length, feel the weird…

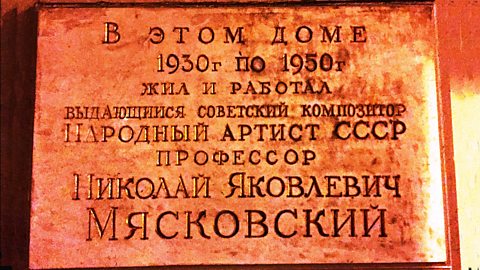

5. Nikolai Myaskovsky – Symphony No. 6 (finale)

Myaskovsky: Symphony No. 6, Op. 23 (finale).

The premiere took place at the Bolshoi Theatre, Moscow on 4 May 1924.

Another hugely original, faintly monstrous choral finale to a symphony to end this week’s list. Shostakovich once called Nikolai Myaskovsky “The Russian Vaughan Williams” (NB. he meant this entirely as a compliment). He’s perhaps better understood as a missing link between Tchaikovsky and Shostakovich himself – a composer with one foot in the soaring melodies of the Romantic tradition, and the other in daring modernism of the 1920s.

Oh, and he wrote 27 symphonies.

Myaskovsky’s tragic, Mahlerian Sixth is often considered his greatest symphony. It depicts the chaos and struggle in the early years of the USSR – notably the composer’s experience of hearing a mass rally at which “Death, death to the enemies of the revolution!” was screamed by the speaker, and the deaths of close family members in bleak, post-revolutionary Petrograd.

The eye-popping finale starts with riffs on French revolutionary songs before sidestepping into the Dies Irae and a traditional Russian Orthodox burial hymn. It’s at this point the choir enters, almost literally wailing with grief and interrupting the sombre hymn. Strange, bizarre and extremely moving, it’s one of the great choral moments in 1920s Soviet music: barely a few minutes long, but once heard, never forgotten.

Further listening on Radio 3...

-

![]()

Choir and Organ

Sara Mohr-Pietsch with an irresistible mix of vocal and organ music.

-

![]()

Breaking Free: A Century of Russian Culture

Radio 3's exploration of the 1917 Russian Revolution and its consequences.

-

![]()

The Essay: Ten Artists that Shook the World

Ten cultural specialists look back at the impact of the 1917 Revolution on artists of the time.

-

![]()

Listen: 30 minutes of glorious Russian music

Stream/download a special In Tune mixtape marking the centenary of the Russian Revolution.