The shock of the rude: A private view of art's naughty bits

20 November 2015

For time immemorial, artists have pushed, prodded and generally messed around with the portrayal of our wobbly bits. And still, it seems, audiences are shocked. STEPHEN SMITH considers how art reflects our conflicting attitudes to our bodies.

In the dear, dead, and largely discredited popular entertainment of my childhood, an unambiguous link between art and sex was robustly articulated. A life class was a lecher’s charter, an undreamt of, ambrosial boon, and the chat-up line that sitcom mothers warned their daughters against was: ‘Want to come up and see my etchings?’

This was the time of the permissive society but, although certain things were permitted, that didn’t mean that they actually happened (or were approved of if they did.)

This is part of an endless pas de deux between culture and sexuality – one minute, as hot as Carmen; the next, rather more of a Nutcracker

Now that we’re all much more easy-going about love and relationships, or hope that we are, what’s really titillating and shocking about art is not sex but money.

This is part of an endless pas de deux between culture and sexuality – one minute, as hot as Carmen; the next, rather more of a Nutcracker, if you’ll overlook the expression.

It goes back to when God was a boy.

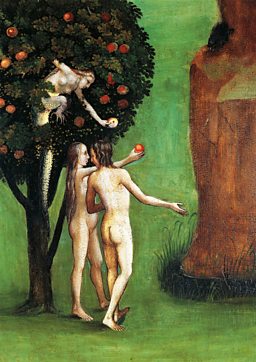

Indeed, if you were looking for a moment when our unsuspecting private parts became ‘rude’, you could do worse than choose the Fall, Adam’s temptation in the Garden of Eden.

The first man and his mate became aware of their nakedness, and were ashamed of it.

Previously, the classical civilizations of Greece and Rome regarded the birthday suit in a rather grown-up way. The Peter Mandelson of ancient Athens, oiled up and reclining on a couch, would have declared himself ‘intensely relaxed about people getting naked.’

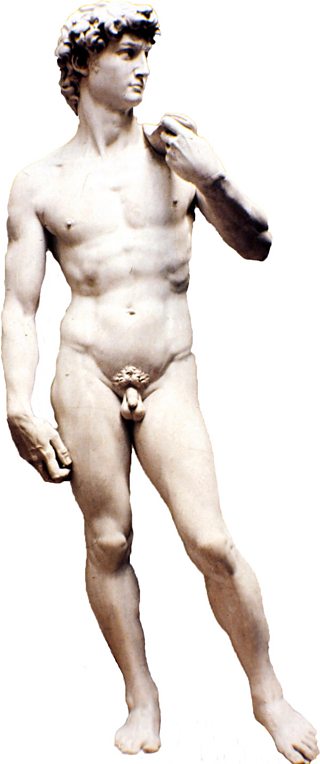

When Michelangelo's David was paraded through the streets of Florence, incensed citizens hurled rocks at it

A man’s body was an advertisement for himself , a kind of fleshy resume on which his character could be read: so many plus points for a noble chin, a finely-turned ankle, etc.

And the great anonymous sculptors of antiquity short-changed men where their successors tend to think it matters most, because a modest portion was understood to denote a chap’s mastery over the baser urges.

One mouthful of forbidden fruit changed all that, and the connection that Christian theology made between carnality and sin led artists to garnish the nether regions with a fig leaf.

This became such an established convention that not even Michelangelo was allowed to defy it.

Harking back to the classical past, he dared to sculpt his famous David in the altogether, but when the statue was paraded through the streets of Florence, incensed citizens hurled rocks at it.

The Victorians were scarcely less apoplectic than the Florentines.

When a cast of the David was installed at what is now the V&A Museum, a bespoke floral brief was crafted for it, to ensure that Queen Victoria never suffered a fit of the vapours on her visits. (This marmoreal jockstrap can still be inspected in the museum’s vaults.)

Although male nudity was insupportable – largely, one suspects, among men themselves – the history of art has been written in the blushing pinks of female flesh.

World-historical canvases like Titian’s ‘Poesies’ after Ovid and the Rokeby Venus by Velasquez, full of voluptuous goddesses at their toilet, were painted for the private delectation of the kings of Spain.

Our own JMW Turner is famous for his phantasmagorical landscapes but, after his death, a scandalized John Ruskin, scented hankie at the nostrils, set a bonfire of the old boy’s rather less well known erotic paintings and sketches, to preserve his reputation.

David's fig leaf, V&A

One can hardly designate these figures as "art" ! If it is, it is a very objectionable form of art.Letter to the V&A from a Mr Dobson, 1903

The antique casts gallery has been very much used by private lady teachers for the instruction of young girl students and none of them has ever complained even indirectly.Reply from V&A director Caspar Purdon Clarke to Mr Dobson

Titian’s ‘Poesies’

The Rokeby Venus, Velazquez

It took two men of science to revolutionise attitudes to the body in art: the theories of Darwin and Freud rocked Christian teaching on creation and human behaviour respectively.

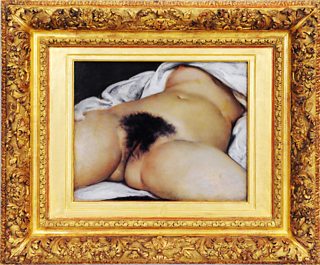

There was nothing priest-approved about Courbet’s painting: it was only Biblical in the biblical sense

Darwin’s On the Origin of Species was published in 1859 and, seven years later, Gustave Courbet unveiled his L’Origine du Monde, a bracingly candid study of a female torso.

There was nothing priest-approved about Courbet’s painting: it was only Biblical in the biblical sense.

The shimmering golden women painted by Gustav Klimt, Freud’s contemporary and neighbour in Vienna, might not have had too much to do with the good doctor’s insights.

The artist’s private portfolio of the same models in a state of much greater déshabillé, however, certainly did.

Of course, rude bits aren’t always rude, always provoking: consider the damaged, alienated nudes of Klimt’s pupil, Egon Schiele; or the cold, glittering hawk’s eye with which Lucian Freud studied his sitters.

And few artists were more notorious in the last century than Balthus, whose girls on the cusp of adolescence were (just about) respectably clothed.

Egon Schiele

-

![]()

Voyeur from Vienna

Egon Schiele's nudes still retain the power to shock and startle.

Gustav Klimt

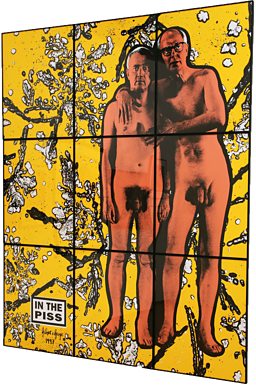

Over time, so-called ‘outsider’ artists who appear to carry a sexual threat grow older and become familiar, and their potency is snuffed out by the policeman’s helmet of public acceptance.

Ask not for whom the rude bits wobble in the gallery... they wobble for thee

An old worthy called the Lord Chamberlain once had to sit through hours of nudie shows in the West End, to make sure that the young ladies didn’t jeopardise public decency by moving: if only he’d known that all he had to do was to declare them national treasures to remove any frisson of danger.

The once outrageous Gilbert and George are practically the Eric and Ernie of art; Grayson Perry and Paul O’Grady could probably get away with doing each other’s gigs.

Art reflects our own conflicting and changing attitudes to our bodies. So ask not for whom the rude bits wobble in the gallery, dear reader, they wobble for thee.

Yes, it’s our own poor pudenda that we see up there on the canvas or the marble, lightning rods in the ever-swirling sexual storm.

Stephen Smith is Culture Correspondent of Newsnight.

Related articles

-

![]()

Allen Jones: The power of desire

Controversial British Pop Artist Allen Jones guides BBC Arts around his Royal Academy retrospective.

-

![]()

Allen Jones: A career in quotes

What the critics said about controversial British Pop Artist Allen Jones.

Related Links

More from BBC Arts

-

![]()

Picasso’s ex-factor

Who are the six women who shaped his life and work?

-

![]()

Quiz: Picasso or pixel?

Can you separate the AI fakes from genuine paintings by Pablo Picasso?

-

![]()

Frida: Fiery, fierce and passionate

The extraordinary life of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, in her own words

-

![]()

Proms 2023: The best bits

From Yuja Wang to Northern Soul, handpicked stand-out moments from this year's Proms