To the cinema, comrades: The revolutionary age of Soviet film posters

7 November 2017

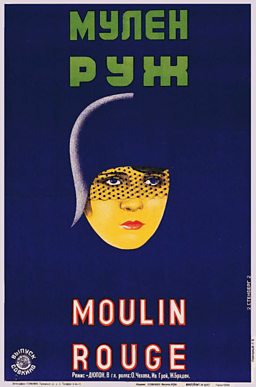

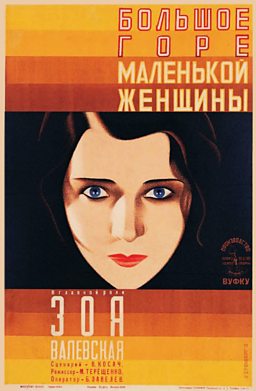

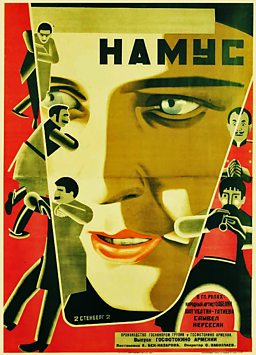

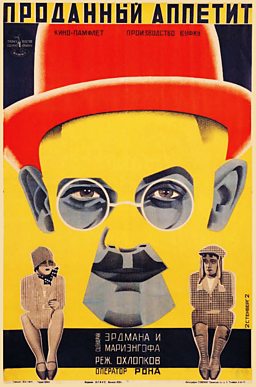

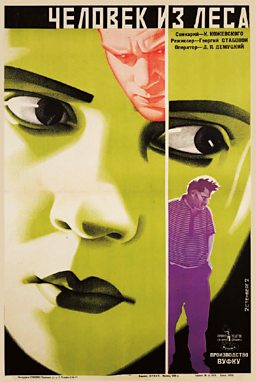

Inspired by the 1917 Revolution, Russians decided that art had an important role to play in the future of the Soviet Union. The visual arts in particular entered an experimental, avant-garde era, where even the design of film posters reached new heights.

Art as collective

After the 1917 Revolution, art had a new official status in the Soviet Union as a positive force for shaping the future of the young State. The new structures and attitudes brought about by the Bolshevik Revolution encouraged artists to experiment in multiple fields.

And, as a socially important force and a propaganda tool, cinema's growth was encouraged throughout the Soviet Union after it had been nationalised by Lenin in 1919.

Sculptors, photographers, architects and graphic designers all came together to work on the exciting new art form of film posters.

All images are from Film Posters of the Russian Avant-garde by Susan Pack, published by Taschen.

Constructivism, comrades!

Constructivism was a new direction in art that was heavily influenced by technology, and featured experimentation with geometry and photomontage. Well-known as the go-to look for propaganda posters, but also used in advertising for beer and food, it would become a big part of Soviet life.

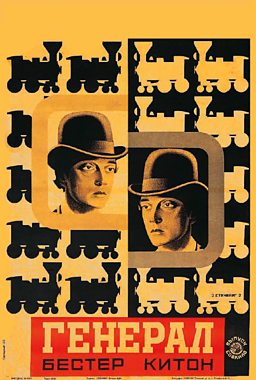

Cinema became huge in Russia in the 1920s. Foreign movies starring the likes of Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks were especially popular.

The State Cinema Enterprise, Goskino, was set up in 1922 and renamed Sovkino in 1926. Sovkino operated four movie studios and twenty-two different production units, and also distributed all foreign films, the profits from which subsidised home-grown movies.

Sovkino's advertising department, Reklam Film, was responsible for designing, approving and distributing film posters throughout the Soviet Union.

"2 Stenberg 2"

Reklam Film was led by graphic designer Yakov Ruklevsky.

We did everything together. It was this way from childhood. We ate alike and followed the same work routine. If […] I caught a cold, he caught a cold too...Vladimir Stenberg

He recruited talented artists including the Stenberg brothers, Georgii & Vladimir, who were extremely prolific and consistently created fantastic images using the latest avant-garde and Constructionist techniques.

The Stenberg brother's photomontages combined realism and the abstract, and the partnership would result in about 300 film posters adorned with the trademark signature “2 Stenberg 2".

Georgii Stenberg died in a car accident in 1933. and Vladimir's later work never quite matched the art produced by the brothers' collaboration.

Other notable poster artists included Nikolai Prusakov, Grigori Borisov, Mikhail Dlugach, Alexander Naumov, Leonid Voronov, and

Iosif Gerasimovich.

Agile art

How these young Soviet poster artists went about their work mirrored the way Soviet directors approached their film assignments. They synthesized the prevalent art trends of their day into a vibrant style of their own.

The turnaround for producing these posters was often hours rather than days. Artists could view a film at a 3pm screening and be required to present the completed poster by 10am the following day.

Printing equipment was old and rickety, usually predating the 1917 Revolution, and the technology was therefore primitive.

The standard of poster art is doubly impressive given that the artists expected their posters to be shown for just a few weeks, before being torn down and thrown away.

1925-30: The golden age

The peak period for the art of the Russian film poster was 1925-30. They are now quite rare - and expensive to collect - because although they were distributed throughout the Soviet Union, the posters were often printed on poor-quality paper which didn't stand the test of time.

But the golden age of Soviet film posters was coming to an end by the early 1930s. Why?

1930s: Stalin shuts down the avant-garde

Art as propaganda was always the preferred state of play for the Soviet Union's leaders. The Constructivist ideals of free expression were an open invitation to ideas that didn't toe the party line. The proletariat's enthusiasm for American cinema didn't exactly please them either.

The Russian revolutionary avant garde movement was radical but it was also brief - Stalin hated it and most of its works were confined to obscurity in the USSR until the fall of communism.

Filmmakers, writers and artists were micromanaged by the state and had their work censored. In 1932 Stalin decreed that Socialist Realism, which glorified the Soviet present and projected a forced optimism onto the future, was now the only official art style of Soviet culture. Artists who refused to comply faced the gulag.

As author Susan Pack says in her book Film Posters of the Russian Avant-garde, "Stalin may have closed the window of creativity, but not before it had illuminated history with some of the most brilliant posters ever created."

Russian season on BBC Four

-

![]()

Revolution: New Art for a New World

Feature-length documentary encapsulating a momentous period in the history of Russia and the Russian avant-garde.

-

![]()

October: Ten Days that Shook the World

This 1928 documentary-style Soviet silent film recreates the events in Petrograd.

-

![]()

Ceremony: The Return of Friedrich Engels

Turner Prize-nominated artist Phil Collins returns Engels to Manchester in the form of a Soviet-era statue.

-

![]()

The Real Doctor Zhivago

Stephen Smith traces the revolutionary beginnings of Boris Pasternak's bestseller.

More from BBC Arts

-

![]()

Picasso’s ex-factor

Who are the six women who shaped his life and work?

-

![]()

Quiz: Picasso or pixel?

Can you separate the AI fakes from genuine paintings by Pablo Picasso?

-

![]()

Frida: Fiery, fierce and passionate

The extraordinary life of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, in her own words

-

![]()

Proms 2023: The best bits

From Yuja Wang to Northern Soul, handpicked stand-out moments from this year's Proms