Main content

Meet Eric, Britain's first robot

Image courtesy of the Science Museum

Well... almost. Eric is actually a faithful reconstruction of a robot made in 1928.

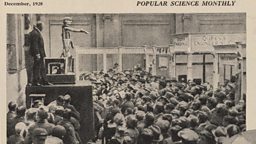

You can see Eric 1.0 pictured below. He was the one of the world’s first robots, and the first ever to be made in Britain – a two-metre technological titan described in the press as an “almost-perfect man”.

Image courtesy of the Science Museum

That regal bearing is no trick of the light. Eric was in fact originally designed as a stand-in for the Queen’s father, the Duke of York.

Image courtesy of National Portrait Gallery, London

Image courtesy of the Science Museum

In 1928, the Duke declined an invitation to attend the official opening of London’s Royal Horticultural Halls, a turn of events that inspired one of Eric’s makers, Captain WH Richard, to remark: “It is a mechanical show – let us have a mechanical man to open it!"

Despite his great height and imposing appearance, Eric was relatively simple by modern robotic standards. But he could stand up, take a bow, move his arms – and deliver an astonishingly good speech, by all accounts.

Yet despite his popularity with the press and public, Eric mysteriously vanished just a few years later. This was a relatively common fate for early robots, which were often cannabilised for parts or melted down for scrap metal.

Years went by and Eric was all but forgotten – until early 2016, when Science Museum curator Ben Russell discovered images and archive footage of Eric in all his walking, talking glory.

Russell became obsessed with the idea of bringing Eric back to life. There was only one problem: the original blueprints were missing. Eric’s original creators had kept his inner workings a secret: the only clues that survived were photographs and an illustrated article from the 1928 Illustrated London News.

Science Museum curator Ben Russell with roboticist Giles Walker. Image courtesy of the Science Museum

Not to be thwarted, Russell joined forces with Giles Walker, an artist with 20 years' experience of building robots. Together they launched a Kickstarter campaign to raise funds for Eric’s triumphant resurrection.

Russell and Walker carefully studied images, newspaper articles and archive footage to identify the movements that the original Eric would have been capable of, and began the process of reverse-engineering the technology that would allow him to rise again.

Modern technology did enable some (strictly uncosmetic) improvements. Eric 2.0 has elbows that allow him to move more freely, for example, and his movements are pre-programmed using software adapted from a theatre lighting system. But while his innards are “a million miles” from the pulleys and gears that controlled Eric 1.0, he moves in exactly the same way.

Best of all, Eric remains one of the most satisfyingly robotic-looking robots in existence – a “moving, talking man of steel” and “the kind of thing a child would draw”, according to his proud custodians.

He’s now the centrepiece of a new Science Museum exhibition about robots, which charts the history of mechanised human forms and their meaning for society.

In Free Thinking: Robots, Matthew Sweet visits the Science Museum’s Robots exhibition to meet Eric, and brings together experts to debate the legal and ethical implications of our increasing reliance on robotics and automation. Listen live or online at the Radio 3 website.

-

![]()

Free Thinking: Robots

What are the legal and ethical implications of our increasing reliance on robotics and automation?

-

![]()

Four artworks that explore what it meant to be Black and British in the 1980s

The story of the British Black Arts movement is steeped in the cultural values of modern Britain.

-

![]()

The dark history of the treadmill

How did this once-feared instrument of torture become one of our favourite pieces of gym equipment?

-

![]()

Nine reasons Victorians thought men were better with beards

A historian of hirsuteness curates the 19th century's best justifications for facial hair.