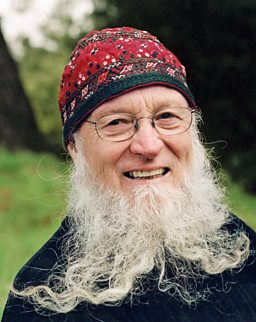

Californian dreamer: Terry Riley at 80

By Brian Morton | 24 June 2015

He once made the man from Bösendorfer cry. It was at the Shaw Theatre in London in 1986 where Terry Riley was due to give a performance of his epic piano piece The Harp Of New Albion, which required a magnificent twelve-foot Imperial to be tuned in just intonation (that is with the note frequencies in ratios of whole numbers) rather than the familiar equal temperament that has been with us since Bach.

The man from the piano company clearly thought this was an act of cultural vandalism on a par with shelling ancient Buddhas. He might well have been converted by the performance later that evening, for The Harp Of New Albion, with its rich mythological underpinning and powerful Atlanticist sweep that takes in everything from Celtic folk forms to classical series to jazz, is one of the great extended piano works of the 20th century, to be set alongside Sorabji's Opus Clavicembalisticum and the late Ronald Stevenson's Passacaglia on DSCH.

In C established Riley as the most daring, but also perversely the most populist, of the so-called American Minimalists

Riley's piece doesn't chew up hours in quite the way of those massively extended pieces, but his work as a whole has dealt with the issue of time in fascinating and original ways, confirming that duration itself has often been a major concern of modernist music.

The seminal In C, originally from 1964 but now an established repertory piece with contemporary ensembles, established Riley as the most daring, but also perversely the most populist, of the so-called American Minimalists.

It's a piece that deploys 53 musical phrases round a flexible but ideally largeish ensemble, conferring on the participants a degree of freedom in execution but a request to remain within a couple or three phrases of the other players.

Stitching the whole thing together is a repeated C quaver (or eighth note in American parlance) usually played on the piano and “traditionally”, as the composer has said, “by a pretty girl”.

Terry Riley's In C, performed in 1986

An extract from a full performance of the piece, originally broadcast on 6 December 1986.

A whole generation grew up nodding gently to Riley's theme or tripping quietly to the dense modal layers of his electric masterpiece A Rainbow in Curved Air, which might be likened to a Bach chorale as reinterpreted by Thomas Pynchon.

A Rainbow in Curved Air might be likened to a Bach chorale as reinterpreted by Thomas Pynchon

Riley's whole enterprise at the time – Rainbow was finished in the cusp year of late modernism, 1968 – was a response to the dogmatic serialism that required most young conservatory-trained musicians to manipulate tone-rows in strict sequences and inversions.

It drew strongly, as Philip Glass's music also did, on Indian models, specifically Hindustani music, where the deployment of modes and repetitive structures incorporating successional change was a key element.

The title piece was a delicious palimpsest of all the electric keyboards Riley had at his disposal, but set to tasks that would have been perfectly familiar to a classical section player, in much the same way as Glenn Branca later used cheap electric guitars to create symphonies out of drowning overtones.

So influential was A Rainbow In Curved Air (title track of the album and the source of the band name Curved Air) that everyone unconsciously knows it from the opening sections of Mike Oldfield's Tubular Bells and from more than one Pete Townshend tune: Won't Get Fooled Again contains a pretty blatant lift, while Baba O'Riley is a joint homage to the American composer and the sage Meher Baba.

The best reason for questioning the national or regional attribution of American Minimalism is that its central adherents generally speaking took their inspiration from other continents. But it's important not to overstate Minimalism's non-native provenance.

Though the generation that included Riley, Glass, Steve Reich, John Adams, Harold Budd and others shared something of John Cage's suspicion of jazz, it had been the dominant American art music of the previous generation and it was impossible to avoid.

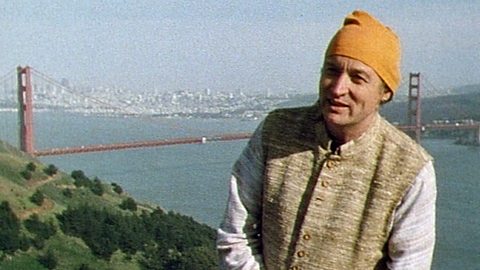

Terry Riley interview in 1986

Riley talks about the origins of his piece In C in this clip from West Coast Story.

Flipsides rarely receive the same attention as title tracks, and on side B of A Rainbow In Curved Air was an altogether jazzier conception called Poppy Nogood and the Phantom Band, which featured Riley's soprano saxophone in a part directly but subversively influenced by John Coltrane's skyscraping improvisations on the small horn.

Under the busy surface, Riley's music usually has a clear logic and a fine sense of humour

Riley himself has suggested that Bud Powell, Bill Evans and Art Tatum have all influenced his piano playing, and it's fascinating to listen to his occasional solo recitals with that in mind, but it was the example of the close-knit improvising combo – whether the Evans trio or the Miles Davis quintet – that really influenced Riley's creation of a tight, clearly directed sound with large areas of improvisational freedom opening out from a highly disciplined structure.

There's a puckish quality to the man and the the music, a very Californian approach – similar to that of Cage, the inventor's son – to practical and technical problems as just 'stuff' that has to be got out of the way so that the music can be addressed.

Nobody seems to have noticed that the 53 phrases of In C might easily be interpreted as a pack of playing cards . . . plus joker. Under the busy surface, Riley's music usually has a clear logic and a fine sense of humour.

When he began to experiment with just intonation around the time of Shri Camel in 1976 [released 1978 but first performed earlier] it was evident that under the heavyweight spiritual titles and dungeons-and-dragons settings - Anthem of the Trinity, Celestial Valley, Across The Lake Of The Ancient World, Desert of Ice - there was a musician who enjoyed simple fixes and direct communication.

There's no God-bothering or transcendence. The presumed Hibernian roots come out constantly in melody so sweetly impersonal it seems to have been around forever.

He may have been classed, alongside Harry Partch, Moondog and Conlon Nancarrow, as a great American 'outsider', but Riley is really the (global) village bard, a storyteller, retired traveller and fireside dreamer who keeps the old tales fresh.

More on Terry Riley

-

![]()

Discovering Music, BBC Radio 3

Charles Hazlewood and the BBC Concert Orchestra examine In C and explore the rise of minimalism.

-

![]()

In C Mali

Watch Damon Albarns' Africa Express collective give Riley's piece an African twist at Tate Modern.

-

![]()

BBC Music: Terry Riley

Biography, clips, tracks and more.

-

![]()

Africa Express: Albarn's odyssey from Mali to Syria via Glastonbury

Performances from The Orchestra of Syrian Musicians, Damon Albarn and Africa Express