Big jaws, big bite?

By Benjamin Moon, scientific consultant for Attenborough and the Sea Dragon

Imagine having a four by four sitting on you… and Temnodontosaurus could still bite with more force!

Fossils are just bones found in the ground, so how can we hope to reconstruct what the animal was like when alive? But bones do more than just sit inside the body. They hold you upright, provide attachment points for muscles, even take part in making cells for the rest of the body. So even though the muscles are long gone – rotted away when the animal died – scientists can still use the remaining bones to work out how animal might have lived.

In the National Museum of Wales in Cardiff, there are some of the most massive jaws ever discovered: the giant head of an ichthyosaur called Temnodontosaurus (tem - no - don - toe - sore - us), found almost 200 years ago by Mary Anning near Lyme Regis, Dorset; not far from where our ichthyosaur was found. The length of this skull is over 1.5 m, and its missing bits – the complete skull may have been over 2 m long. While we don’t have the whole body, we can estimate that this Temnodontosaurus was around 8–10 m in length: one of the largest ichthyosaurs ever discovered! The skull of ichthyosaurs one of its most important parts. This is where the action goes on: the biting and eating that it may have spent much of its time doing.

There are many features that suggest that Temnodonotosaurus was the top predator in the seas in the Early Jurassic (200 to 190 million years ago). The sheer size of this ichthyosaur is much larger than any other animal around at the time. Also, the jaws and teeth are very large, and some of the teeth have ridges going along their length. These would have acted similar to a knife-blade, cutting through flesh. This was not a gentle giant like a whale – only eating tiny krill – this was more like an orca: hunting whatever animals it could get its teeth into.

To find out how devastating the bite of Temnodontosaurus was, we calculated the force that it was able to bite with. To do this we needed to find out how much force the jaw muscles could create. We worked out how much muscle you can fit into the skull of our Temnodontosaurus using a combination of CT scanning to see inside the skull and surface scanning to get the outside shape. There are four major groups of muscle that close the jaw. We calculated that there is space for over 5000 cm³ of muscle.

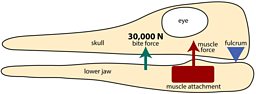

Next we worked out how much force this could close the jaws with. In ichthyosaurs, the jaw acts like a third-class lever: at the back is the jaw joint, which is where the lower jaw rotates to open; this acts like the fulcrum. The muscles are attached in front of that and pull the lower jaw up to close it and bite. Further forward is where the victim is, ready to be pierced by the teeth. This form of lever means that the most powerful bite is at the back of the jaw. With 5000 cm³ of muscle ramming the jaws shut, we calculated that Temnodontosaurus closed its jaws with over 30,000 N or over 3 tonnes of force.

For comparison, this is about twice the bite force to that of a large saltwater crocodile. It’s more than a great white shark too. Imagine having a four by four sitting on you… and Temnodontosaurus could still bite with more force! Its bite may not be quite as strong as Tyrannosaurus rex, but it surely would have made a meal of any animal that got caught. This is the first time that the bite force has been calculated for an ichthyosaur, and shows that Temnodontosaurus deserved its place at the top of the food chain in the early Jurassic seas.

Benjamin Moon is a Researcher at the University of Bristol working on ichthyosaur anatomy and function. For more information about fossils and his work, follow him on @moononthebones or read his blog.