William Shakespeare's America by Robert McCrum

In the two-part Radio 4 documentary Shakespeare and the American Dream, Robert McCrum journeys across Obama's America to find what Shakespeare means to Americans today. Here, he shows how the Bard has long been established in the cultural life of the USA.

O, how I faint when I of you do write,

Knowing a better spirit doth use your name,

And in the praise thereof spends all his might

To make me tongue-tied speaking of your fame.

- William Shakespeare, Sonnet LXXX

Soon after the UK broadcast of the first episode of Shakespeare and the American Dream, I received this letter from one of our listeners:

"As a child I went to school for a while in New York. My first teacher there was an Italian American, Alex Perucci. He was an Anglophile, but more than anything he was besotted with Shakespeare, and did more to instill a love of Shakespeare than any of my subsequent teachers back here in the UK when I started boarding school at the age of 12 in Sussex.

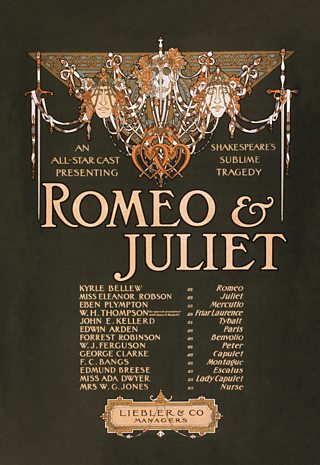

"Mr Perucci referred to him as ‘Billy the Snake’, but his love and passion for the Bard was profound and all encompassing. We looked at so many of his plays. We made our own performance of Romeo and Juliet at the age of nine or 10 (I was the apothecary), and I recall the class being ushered into the school hall to watch Zeffirelli’s production of the same projected on a screen.

"I have no idea why I am telling you this, other than to reinforce that as a Brit, my association with Shakespeare is utterly rooted in the American part of my upbringing."

This letter indicates how deeply woven Shakespeare is into the texture of American life at every level, from the schoolroom to the White House – and for this simple reason: Shakespeare and the ‘American Dream’ have gone hand in hand for 400 years. Why? Because there’s an old affinity between our national poet (and playwright), and those pioneer Americans.

If dramatists and explorers share an addiction to conflict, jeopardy, and transgression, then Shakespeare and the first American settlers had rather more in common than their mother tongue. 400 years after the death of our national poet, and the subsequent landing of the Mayflower, the playwright who is an icon of Englishness has also become a central feature of the American dream, in which the mirror of his great dramas gets held up to a society perpetually in search of itself. When President Bill Clinton says “our engagement with Shakespeare has been long and sustained: generation after generations of Americans has fallen under his spell“, he’s acknowledging this most surprising fact – that Shakespeare’s afterlife as the greatest playwright who ever lived is now as much an American as a British phenomenon.

There’s no question that some early Americans were stage-struck. Consider, for instance, this bizarre episode of American soldiering. In January 1846, about half the US army could be found marshalling under General John B. Magruder in Corpus Christi, a garrison town described by one officer as “the most murderous, thieving, gambling, cut-throat, God-forsaken hole” in Texas. The US Congress had just annexed the lawless slave-state, and was spoiling for war with Mexico.

But it was not all sabre-rattling down on the Latino border. To entertain a restless army, lisping General Magruder, known to his men as ‘Prince John’, commissioned an 800-seat theatre and began rehearsing an am-dram production of Othello. His privates-on-parade included James Longstreet (later a renowned Confederate army general) who was to play Desdemona.

But Magruder had a problem. At six feet tall, Longstreet was badly miscast. Instead, the general turned to a young lieutenant, one Ulysses S Grant (135 lb and just five feet seven in height) who would eventually lead the Union forces to victory in the American Civil War, and later become the 18th US president. Grant threw himself into the part of Desdemona. When Magruder gave him the role, it was said that the young officer “looked very like a girl dressed up”. Now there was another snag: his Othello, a certain Theodoric Porter, wouldn’t have it, complaining that he could not “pump up any sentiment” for Grant as Desdemona. Faced with a thespian hissy fit, Magruder behaved like any good producer: he replaced his young Lieutenant with a professional actress from New Orleans – and the show went ahead.

Reflecting on this episode, another American Shakespeare scholar James Shapiro, author of 1599: A Year in the Life of William Shakespeare, observes that: “To think of the man who would lead the North to victory in the Civil War seeing slavery through the eyes of a white woman married to a black man is something you need to know about America that you won’t find in the history books.”

The works of William Shakespeare had been an integral part of American life since the first settlement of the 13 Colonies, in part through the accident of timing. The Pilgrim Fathers set sail just two years before some actors from Shakespeare’s Globe clubbed together to commission a volume of his plays. So The First Folio and the first Americans became informally twinned in a fortuitous assertion of originality. Shakespeare spoke to the first Americans in other ways, too. So far as we know, he never ventured onto the Atlantic, but he was fascinated by sea voyages and sinkings. Some of his greatest works, notably Twelfth Night and The Tempest, begin with shipwrecked sailors. Stranded Viola’s “What country, friend, is this?” would have been a question familiar to generations of American settlers.

About a hundred years after the landing at Plymouth Rock, reports of Shakespeare productions start to creep into the record. The first recorded performance of a Shakespeare play in the New World (Romeo and Juliet in New York City) took place in 1730. Colonial America was still in an early phase of its reverence for Shakespeare. English puritans had been fiercely anti-theatrical, so it’s no surprise that their American cousins should view actors and acting with suspicion. As late as 1774, the continental Congress was urging the people of Philadelphia to shun the “extravagance and dissipation” of the theatre.

The revolution changed everything. For a start, it brought to prominence a generation of Shakespeare-lovers. On 14 July 1787, for instance, in the middle of thrashing out the details of the new constitution, Washington broke away from the legislative haggling to watch a production of The Tempest. During the revolutionary war of 1776, a popular production of Othello in New York City saw blacks and whites mingling together with unprecedented freedom. As Shakespeare became the means by which discordant elements in US society could find harmony, his plays became part of the debate about what it meant to be an American. Elsewhere, the first line of Hamlet – “Who goes there ?” – explicitly raises the identity question. Meanwhile, plays like Othello and Richard III allowed new Americans to explore new and troubling questions that would otherwise have been hard to articulate or admit to.

Americans might no longer refer to England as their mother country, but Stratford remained a popular tourist destination. When Jefferson and Adams visited in 1786, the author of the Declaration of Independence “fell upon the ground and kissed it”, and paid a shilling to see Shakespeare’s grave. “Let me search for the clue which led great Shakespeare into the labyrinth of human nature,” Adams wrote in his diary. “Let me examine how men think.”

When Tocqueville toured the states in the 1830s, he described the immense and widespread popularity of Shakespeare. “There is hardly a pioneer hut,” he wrote, “in which the odd volume of Shakespeare cannot be found.” The plays, he reported, were almost as popular as the Bible. Shakespeare had become such good box office by the middle of the 19th Century that the great showman PT Barnum tried, unsuccessfully, to ship “the birthplace”, a restored half-timbered house on Henley Street, back to the States. In Victorian times, the New World exhibited a far more sustained and widespread popular interest in his plays than the old country. Occasionally, the passions inspired by Shakespeare got out of hand. In 1849, there was a riot, provoked by competing productions of Macbeth, in Astor Place, New York City, now the home of the Public Theatre. Bitter rivalry between the British star William Charles Macready and Edwin Forrest, an up-and-coming American actor, boiled over in the playhouse, spilled out onto the streets and led to a violent showdown between well-to-do Macready devotees and some American working-class Forrest fans. The National Guard was called out. In the ensuing melee 20 people were killed and perhaps a hundred injured.

The Astor Place riots were unprecedented. In general, Shakespeare served as a benign lightning rod for the contentious issues in American political and economic culture. The plays became a medium through which the complexity of American society, and its many unresolved tensions, could be debated.

Shakespeare productions were a constant feature of frontier life in the West. When Los Angeles became the company town for an emerging film industry, Shakespeare shape-shifted again, becoming part of Hollywood Westerns. He had already been performed by itinerant companies up and down California for decades. In John Ford’s My Darling Clementine, starring Henry Fonda, the itinerant Shakespearean actor Granville Thorndyke, played by Alan Mowbray, performs “To be or not to be” to a bar full of desperadoes before grandly declaring that Shakespeare is not “meant for taverns or tavern louts”, a line that sparks an inevitable gun fight.

Perhaps the apotheosis of the marriage between Shakespeare and the New World occurs with West Side Story. The most famous 20th Century musical adaptation of Shakespeare began in 1949 when a friend of the director Jerome Robbins was offered the part of Romeo in a stage production and began puzzling about bringing the role to life. Robbins’ reaction, however, was more Shakespearean. “I said to myself,” he later recalled, ‘’’there’s a wonderful idea here’.” Having begun to lift a story of ill-fated lovers and gang violence, Robbins approached Leonard Bernstein and the librettist Arthur Laurents. Eventually the young Stephen Sondheim came on board to write the lyrics.

Sondheim, speaking to me at home in Manhattan last summer, remembered that “I had no particular interest in the subject matter, but I knew I wanted to work with Bernstein, Arthur and Jerry. We never checked Shakespeare’s text. I don’t think any of us picked up that script once Arthur had written the book.”

Today, Sondheim has become a passionate follower of Shakespeare productions around the world, and especially in London. “I just can’t believe Shakespeare,” he says. “I mean, I can’t believe that one man did all this. Shakespeare is – oh, come on – some of his lines always make me cry.” Sondheim is rather less emotional about the relationship between West Side Story and Romeo & Juliet, a play in which, as he puts it, “so much happens”. He describes it as “a melodrama with something extraordinary happening in every scene”.

2016 is a big year for Shakespeare in the UK, but it will also be the year in which we see an indigenous American Shakespeare celebrated across the USA. Shakespeare remains at the centre of the things Americans disagree about: the issue of race; the issues of leadership, belonging, and national identity. These are all Shakespearean questions, and his work is where Americans conduct their age-old debate about ‘Who is an American?’

More from Seriously...

-

![]()

Seven Lyrics to Use in Conversation Today

These song lines have become common parlance.

-

![]()

Five Women Who Wrote Rock

These writers helped define rock journalism in the 1960s.

-

![]()

Is Mindfulness Meditation Dangerous?

Jolyon Jenkins investigates whether meditation can do you more harm than good.

-

![]()

Neil Innes on the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band

The band member recalls the anarchistic joy of a truly unique group.

-

![]()

Fake It 'Til You Make It

Why have fakes and fantasists always fascinated us?

-

![]()

Mary Beard vs Hair Dye

The writer and academic has a consultation with a legendary hair colourist.

-

![]()

The Recovering Addicts Who Inspired Trainspotting

The team of recovering addicts who made their mark on cinematic history.

-

![]()

Mao's Little Red Book Goes West

David Aaronovitch on how an Eastern political tract became a Western icon.

-

![]()

David Bowie in his Own Words

David Bowie's interviews reveal his humour, passion and determination to succeed.

-

![]()

Dotun and Dean

Broadcaster Dotun Adebayo revisits his youthful obsession with James Dean.

-

![]()

Gavin Esler on The Good Goering

Did Nazi leader Hermann Goering have a brother who saved innocent lives from the Holocaust?

-

![]()

10 Women Who Changed Sci-Fi

A selection of great female authors who have radically altered the genre.

-

![]()

Meet the Burlesque Legends

Mat Fraser meets the former striptease stars back on the stage in their 70s and 80s.

-

![]()

Philip Hoare: CSI Whale

The award-winning writer on porpoise dissections, stranded whales and beached dolphins.

-

![]()

Lord Byron and the Hebrew Melodies

Michael Rosen tells the little-known story of how the poem She Walks in Beauty was set to Jewish music.

-

![]()

Black, White and Beethoven

Joseph Harker asks why Britain's classical music scene remains so resolutely white.

-

![]()

Tim Key and Gogol's Overcoat

Comedian Tim Key spins his own surreal tale of one of Russia's greatest short stories.

-

![]()

Editing Life

Matthew Cobb explores the excitement and concerns about the new genome editing technology.

-

![]()

Herman Melville's Sea Change

Moby-Dick was made in England. Paul Farley tells a story of fast fish and loose fish.

-

![]()

Embarrassment

Journalist Lynne Truss prepares to cringe as she investigates embarrassment.

-

![]()

Mao's Little Red Book Goes West

David Aaronovitch asks why Mao's Little Red Book captured the imagination of the west.

-

![]()

Invisible Belfast

A mysterious note sends a visitor to Belfast on a labyrinthine journey through the city.

-

![]()

Gay Bombay

Zareer Masani returns to Mumbai to measure India's changing attitudes to homosexuality.

-

![]()

Unnatural Selection

Adam Hart reveals how humanity is altering the evolutionary paths of other creatures.

-

![]()

David Bowie: Verbatim

David Bowie's extraordinary life and career told in his own words.

-

![]()

Herland

Geoff Ryman explores stories about women and men in future worlds. Plus original story No Point Talking.

-

![]()

The Good Goering

Gavin Esler tells the story of Hermann Goering's brother, who claimed he saved people from Nazi persecution.

-

![]()

Trump and the Politics of Paranoia

The story of how ethnic fear has been used from the republic through to Donald Trump.

-

![]()

Crafty Orchids

Why are orchids so popular? Jim Endersby offers a new scientific history of their allure.

-

![]()

Utopias

Michael Symmons Roberts the book behind one of our most influential ideas: Utopia.

-

![]()

Raising the Dead

Composer Adam Gorb goes on a journey to listen to the lost music of concentration camps.

-

![]()

Catacombs of the Mind

The late Bruce Lacey reflects on his life in this 2014 documentary.

-

![]()

I Dressed Ziggy Stardust

Samira Ahmed meets British Asian women who, like her, were inspired by David Bowie.

-

![]()

How My Sister Said Goodbye

Before she died, Jonathan Freedland's sister's left a unique audio legacy - her own Desert Island Discs.

-

![]()

The Selling of Sinatra

A centenary celebration of the life and work of Frank Sinatra.

-

![]()

Strictly Russian

Bridget Kendall asks why the Russians are one step ahead in the world of ballroom dancing.

-

![]()

When Britain Had the Right Stuff

Archive on 4 uncovers the forgotten history of Britons in space.

-

![]()

JFK: The Vinyl Reaction

How the American record industry responded to the assassination of President Kennedy.

-

![]()

Blood, Sex and Money: The Life and Work of Emile Zola

Glenda Jackson travels to Paris for documentary about influential French writer Emile Zola.

-

![]()

A Man's a Man for a' That: Frederick Douglass in Scotland

The story of abolitionist and freed slave Frederick Douglass's time in Scotland.

-

![]()

The Jazz Ambassadors of the Cold War

Julian Joseph recounts how jazz diplomacy was used during the Cold War.

-

![]()

Attention Must Be Paid - Arthur Miller's Centenary

Christopher Bigsby traces the life and work of Arthur Miller, mostly in Miller's own words.