Virtual unreality: Adam Curtis on why your life doesn't make sense

14 October 2016

Filmmaker, story teller, propagandist, revealer of strange truths. Through documentaries such as The Century of the Self, The Power of Nightmares, and Bitter Lake, Adam Curtis has forged a career explaining the hidden undercurrents that have shaped the 20th Century. Stitching together disparate film archive, his visually jarring tales push a similar message - the world we call real is just illusion. With HyperNormalisation, a new three-hour iPlayer exclusive launching on Sunday, ALASTAIR McKAY takes a trip through the conspiracy-strewn world of Adam Curtis.

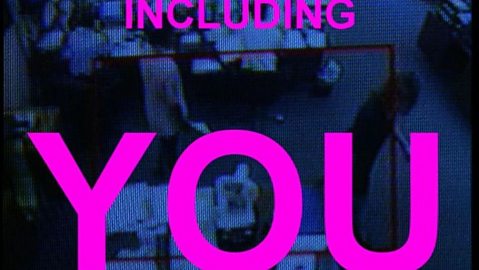

What is the audience supposed to think after 165 hyperactive minutes of Adam Curtis’s media massage HyperNormalisation?

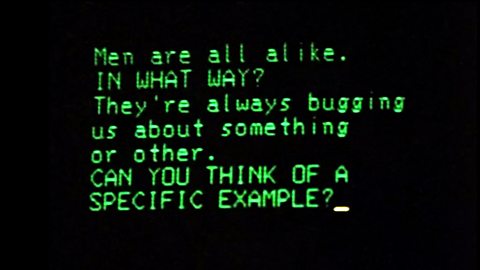

An element of confusion would be natural, because the film is aggressively ambitious and is assembled with flair, though the ambition is flattered by the structure, which splices dislocated clips, an ominous electronic soundtrack, and an authoritative voiceover. It looks like a Massive Attack video, but is placid in tone, even when peddling questionable assertions.

It looks like a Massive Attack video, but is placid in tone, even when peddling questionable assertions

Some of it is reasonable. Some of it is inarguable. There are leaps into the void. “We live in strange times,” Curtis asserts. “And no one has any idea of a different, or better, kind of future.”

Is Curtis’s film fact or fiction? Well, it is an essay, and possibly a tract, so it has a point of view. Mostly, that point of view is about the difficulty of having a point of view, and of discerning the difference between fact and fiction in this media-saturated age.

You might, just about, be able to construct a Photo-Fit of Curtis by unpacking his obsessions (Disappointed idealist? Let down by the 1960s? Angered by the rise of corporate power and globalisation? Interested in technology and the freedoms it seems to offer? Frustrated by that technology, and the uses to which it is put?). Perhaps you could have a stab at his temperament. (Sardonic? Mischievous? Rebellious?). But after all that, what would be left?

A sense of bewilderment, certainly. Because HyperNormalisation is a tapestry of disinformation; a theory of everything in which world events - sometimes funny, mostly tragic - are transposed, until reality is mediated into an endless happening. When it works, it’s brilliant.

Here’s the young, beautiful, vague Patti Smith peering at the graffiti of bankrupt mid-1970s New York, used to illustrate the retreat of artists from political engagement. “Look at that,” Smith coos. “Isn’t that cool? I love when kids write all over the walls.”

And while Smith and other punks scuttle into ironic detachment, Donald Trump is buying up New York, using borrowed loot he will later lose, then re-acquire, having reinvented himself as a brand.

At the same time, futuristic hippies such as the Grateful Dead lyricist John Perry Barlow are imagining an electronic frontier which will build on Timothy Leary’s predictions of an alternative reality in which cyberspace is a liberating force, an electronic LSD. What could possibly go wrong?

Curtis unfurls a montage of disaster movie clips in which American buildings are destroyed by aliens and terrorists

Ninety or more minutes in, Curtis reaches 9/11, having hurtled through the implosion of the Soviet empire and the rise of aerobics (“Jane Fonda gave up socialism and started another revolution, trying to change the world was too complicated”).

And by now, we know, or think we know, by staring at this catherine wheel of conspiracy, that the murderous activities of Osama Bin Laden - assuming he did them… because the Lockerbie bomber wasn’t the Lockerbie bomber, that was Ronald Reagan and Henry Kissinger’s fault … because their cynical fantasies led to the creation of Colonel Gaddafi as “a fake terrorist mastermind”, a global super-villain who would be interviewed by Sir David Frost and championed by the Nation of Islam …

Anyway, after all that, but before the bit about Nicolas Cage’s role in the myth of the weapons of mass destruction in Iraq, we get to the part where the soundtrack is Suicide’s Dream Baby, Dream, a piece of music which is both soothing and alarming, because it sounds like Elvis trying to lull a malfunctioning android to sleep.

And here, instead of reality, Curtis unfurls a montage of disaster movie clips in which American buildings are destroyed by aliens and terrorists, and this was before 9/11 actually happened, and it shows, he says, “how everyone became possessed by dark foreboding, imagining the worst that might happen.”

What does it all mean? Is cinema contagious? Did disaster movies lead to copycat catastrophes, or is that just the dark irony of an event that is so unbelievable we’d rather file it as fiction?

What is HyperNormalisation? The term comes from the Soviet Union, to describe a state where everyone knew they were living a lie

Advanced players should be aware that Curtis’s dystopia gets deeper and darker as he goes on, and occasionally, you wish he’d stop the world and drill into the detail, instead of hankering after the effect.

What is HyperNormalisation? The term comes from the Soviet Union, to describe a state where everyone knew they were living a lie, but the fakeness became familiar. It has been taken a stage further in post-Soviet Russia, by Vladimir Surkov, the avant garde theatre director and demiurge of the Kremlin, who has devised the strategy of “non-linear warfare” to keep the populace in a state of obeisance.

And since we’re talking about unbelievable fictions, what about the 1980s’ US government programme, in which a fake conspiracy about alien visitations was leaked through gullible individuals in order to disguise a weapons testing programme? Mulder and Scully were right. Or at least getting paid twice.

What is the audience supposed to feel? Numbness is an option. You might want to invest in a tinfoil hat, to deflect the hypermisery. But asking awkward questions may be Curtis’s point. He is, at heart, a propagandist. It takes one to know one. But unlike the dark images assembled in his collage, he aims to stimulate rather than pacify. He wants to make his audience think.

Failing that, he knows where to find that clip of the sneezing panda.

HyperNormalisation will be available to watch on BBC iPlayer from 9pm on Sunday 16 October 2016.

Trailer: Hypernormalisation

Trailer for the 2016 Adam Curtis film - exclusive to BBC iPlayer

Trailer for the 2016 Adam Curtis film - exclusive to BBC iPlayer

Adam Curtis on BBC iPlayer

Clip: Massive Attack vs Adam Curtis, 2013

Taster clip for Massive Attack v Adam Curtis show at Manchester International Festival 2013

Taster clip for Massive Attack v Adam Curtis show at Manchester International Festival 2013

More blogs from Adam Curtis

Related Links

More from BBC Arts

-

![]()

Picasso’s ex-factor

Who are the six women who shaped his life and work?

-

![]()

Quiz: Picasso or pixel?

Can you separate the AI fakes from genuine paintings by Pablo Picasso?

-

![]()

Frida: Fiery, fierce and passionate

The extraordinary life of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, in her own words

-

![]()

Proms 2023: The best bits

From Yuja Wang to Northern Soul, handpicked stand-out moments from this year's Proms