What is 'The Ring' about? - An Introduction

An introduction to Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelung (The Ring of the Nibelung)

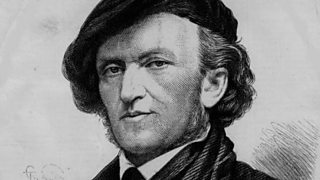

Picture: Richard Wagner

Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungen (The Ring of the Nibelung) is the largest musico-dramatic work ever written, and for many people also the greatest.

Its size and its quality are not unrelated, for its length – four separate dramas, adding up to fourteen hours or more of music – enables Wagner to explore in depth a range of issues which are central to any civilised person’s life: Which things do we value most, and what sacrifices have to be made, if any, of some of those things if we are to have others?

The very opening of the Ring, the prelude to Das Rheingold, not only evokes the bottom of the Rhine, but also the beginning of everything. As soon as life appears, in the form of teasing and lovely Rhine-maidens, lust comes into the world, in the form of an ugly dwarf, Alberich (the Nibelung of the whole work’s title), who desires them but is repulsed by them, so that he renounces love in return for the Gold which they are supposed to guard, and which is alleged to give its owner power over the whole world.

So immediately we are confronted with the issue of the relationship between Love and Power, and that is explored in ever-widening circles, as the chief god Wotan, who has limitless aspirations after beauty, truth and goodness, also finds that he can only realise them by compromise and corruption.

The situation in the first drama seems so dark that a new start is required: but how? Can the beings responsible for the old mess create new beings who won’t be implicated in it – heroes who are free, yet do what the old guard wants them to?

As the Ring progresses we are flabbergasted by the range of issues it confronts, the vividness of the characters who fill it, above all by the ceaseless inventiveness and inspiration of its music, which Wagner composed over a long span.

He began writing the music in 1854, and only completed it twenty years later, though with a twelve-year gap after Act II of Siegfried, the third part of the tetralogy (though Wagner insisted that it was “a trilogy with a preliminary evening”). During that time Wagner grew immeasurably as a composer, and his attitude to the questions posed in the Ring altered drastically too, but his creative integrity was such that nothing in the work could be mistaken for anything in any other of his operas (or dramas, if you prefer), and the construction of the whole is so strong that, powerful as its individual parts are, the cumulative effect of seeing and listening to it in a short space of time is overwhelming in a way, and on a scale, that has no parallel in the whole of human achievement.

One feels, at least for a bit, transformed and uplifted by the Ring, even though it shows the world in a state of terminal disintegration.

© Michael Tanner/BBC