Is the synth the ultimate feminist instrument?

If, as Virginia Woolf famously wrote, women need “a room of one’s own” to write in, then music’s equivalent might be the “sound-houses” conceived by 17th-century author Francis Bacon and adopted by Daphne Oram as a motto for the sonic wizardry conducted at the BBC Radiophonic Workshop.

But as Oram’s own innovations proved, these sound-houses were virtual, not physical palaces of experimentation. With the invention first of tape and oscillators, then synthesisers, 20th-century music was cut free from the limits of traditional instruments. Women who were lucky enough to gain access to the world of electronic music found themselves explorers in uncharted territory. Without aeons of cultural baggage dictating the ‘correct’ way to make music, they could let their imaginations roam wild, minus the assistance or approval of male producers or musicians.

These days, their spiritual daughters no longer have to get to grips with knobs and patch leads when synthesisers can exist on a laptop, tablet or in the cloud. Think Holly Herndon using the modular sandbox of Max/MSP to reflect today’s hyperreal world back at us, or Columbian live coder Alexandra Cárdenas using open-source programmes such as Supercollider and Tidal Cycles for the on-the-hoof delights of algorave.

To celebrate the inaugural Oram Awards, taking place at the Turner Contemporary in Margate on 3 June 2017 to champion female innovation in sound and music, here are five more pioneering women and the technology they made their own...

Verity Sharp will be featuring the Oram award-winners on Late Junction on BBC Radio 3 on Tuesday 6 June.

Such are Kate Bush’s talents as a singer, songwriter and undisputed queen of the wafty sleeve that her studio genius is often overlooked. But Bush was among the first to see the potential of the Fairlight CMI, one of the first sampling synths when it launched in 1979.

Fairlight users could pitch-shift sounds via its keyboard, or edit the waveforms on-screen with a lightpen. Revolutionary stuff, even if having just 208KB of RAM meant that the samples had to be less than a second long.

Introduced to the Fairlight by Peter Gabriel, Bush worked its often jarringly bit-crushed samples into her 1980 third album Never For Ever – notably the sounds of shattering glass on her hit single Babooshka – but got really stuck in to exploring its unearthly textures on the follow-up, The Dreaming, her first self-produced album.

Key track: Pull Out the Pin

-

![]()

▶ Babooshka

Kate Bush

If you think computer music has no soul, you clearly haven’t heard what Laurie Spiegel could do with some code and a catchy acronym. While working at Bell Labs in the 1970s, Spiegel used the pre-MIDI era software GROOVE (Generated Real-Time Output Operations on Voltage-Controlled Equipment), harnessing computer power to control pitch, sound envelopes and effects on analogue synths. The results, as heard on her 1980 album The Expanding Universe, have an almost Bach-like beauty in their mathematically sculpted forms.

Spiegel went on to develop the algorithmic composition software Music Mouse for Apple Macs. But her most lasting achievement may be her realisation of Johannes Kepler's Harmonices Mundi, which has spent the last 40 years roaming beyond our solar system as the opening track on the Voyager Golden Record.

Key track: Patchwork

-

![]()

▶ Patchwork

Laurie Spiegel

Having studied with and assisted Pierre Schaeffer and Pierre Henry, Éliane Radigue struck out in a different direction from the two giants of musique concrète when she discovered synthesisers. Informed by her dedication to Buddhist meditation, in her hands the ARP 2500 became a gateway to transcendent experience.

In works such as 1986’s Jetsun Mila, drones, overtones and pulses slowly unfold at the edge of perception. Very little changes – until suddenly you realise that everything is different.

Since 2004 Radigue has retired the ARP in favour of acoustic instruments, but still creates music of breathtaking tranquillity and grace.

Key track: Jetsun Mila

-

![]()

▶ L'Île Re-Sonante

Éliane Radigue

Synths as we know them were yet to be invented when Else Marie Pade was busy becoming Denmark’s godmother of electronic music. Instead working with found sounds, oscillators and tapes, she paralleled Daphne Oram by creating out-there compositions for 1950s Danish radio.

Her 1958 work Syv Cirkler (Seven Circles) was the first purely electronic composition to be broadcast on Danish radio. Inspired by a visit to the futuristic Philips Pavilion at the World Exhibition in Brussels, its serialist structure reflects the movements of the cosmos.

Key track: Syv Cirkler

-

![]()

▶ Cirrostratus

Else Marie Pade

Annette Peacock acquired an early Moog synthesiser when working with her then-husband, jazz pianist Paul Bley. After spending several months figuring out how to work the unwieldy beast, the couple started performing with it under the name The Bley-Peacock Synthesizer Show.

Peacock couldn’t match Bley’s adeptness on the keyboard so she found her own way of harnessing the Moog’s unique tone by using it to manipulate her voice, turning her sassy, laid-back vocals into something altogether more alien. Her 1972 solo album I’m the One shows this to great effect, combining jazz, funk, rock and electronics into a circuit-frying psychedelic jam.

Key track: I’m the One

-

![]()

▶ I'm The One

Annette Peacock

By Abi Bliss

More from Late Junction

-

![]()

Late Junction

Max Reinhardt previews the 2017 Oram Awards.

-

![]()

The Oram Awards

The Oram Awards will celebrate Innovation in sound.

-

![]()

Reflections on the Oram Awards

Verity Sharp on the winners of the awards.

-

![]()

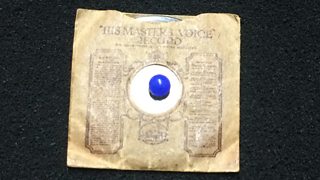

The smallest playable record in the world?

It measures just 3.5 cm in diameter.