Positive force: The pioneering early photography of Julia Margaret Cameron

14 December 2015

2015 is the bicentenary of photographer Julia Margaret Cameron's birth and the 150th anniversary of her first - and only - museum exhibition of her photographs at the V&A, organised by its founding director Henry Cole. Two new exhibitions celebrate this pioneer of photography: the V&A reprises its 1865 show with 100 photographs; while the Herschel Album - 94 prints gifted by Cameron to her friend and mentor, the scientist Sir John Herschel - can be seen at the Science Museum. NATALIE BUSHE considers Cameron's life and work.

A trail-blazer and an idealist - in a discipline she only embraced at 48 - Julia Margaret Cameron took up photography in 1863 when her daughter Julia and son-in-law Charles Norman gave her a sliding wooden box camera as a Christmas present.

Born Julia Margaret Pattle in India to prosperous parents, her family were known for being unconventional, and for being genial hosts to their network of illustrious friends.

When focussing and coming to something which, to my eye, was very beautiful, I stopped thereJulia Margaret Cameron

One such, the writer William Makepeace Thackeray, coined the term ‘Pattledom’ to describe the energy and vitality of the seven sisters. This zeal also characterised Julia's approach to her art (and it was art, she insisted).

Significantly, Cameron met the astronomer and photochemistry pioneer Sir John Herschel while convalescing at the Cape of Good Hope, South Africa in 1836. Herschel is credited with coining the terms 'photography', 'positive' and 'negative' in reference to photographic images. They would become lifelong friends.

She also met her future husband, Charles Hay Cameron, there in the same year. He was a distinguished liberal reformer who in 1835 had published two essays; a critique of the tradition of duelling and On the Sublime and Beautiful, the latter of which explored questions that would become fundamental concerns of Julia's own art.

The Camerons married in 1838 and spent ten years in Calcutta, with Julia latterly becoming its foremost society hostess through organising the functions of the Governer-General of India, Lord Hardinge. They had six children of their own. Herschel also corresponded with her during this time about the latest discoveries in photography.

The Camerons retired to England in 1948, living in Tunbridge Wells then London. Charles spent extended periods at the coffee and rubber estates they owned in Ceylon. In 1859, during one such period, Julia visited Alfred, Lord Tennyson's new home at Freshwater on the Isle of Wight.

Inspired by the place, she subsequently purchased a cottage nearby, naming it Dimbola Lodge after one of the Ceylon estates, and it became the Camerons' home from 1860.

When photography became her passion, she set out to realise its potential as an art form. The hen house at Dimbola was converted to a glass house, and the coal-house to a dark room. She had no formal training and experimented with the process on a trial and error basis.

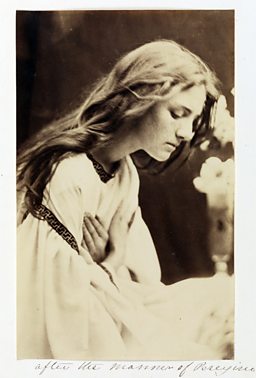

Cameron explored a variety of photographic subjects, which she herself categorised as Portraits, Madonna Groups and Fancy Subjects for Pictorial Effect in a hand-written contents page for an 1865 album for art collector Lord Overston.

She excelled in portraiture and, as an 1866 review in MacMillan's Magazine put it, her "position in literary and artistic society gives her the pick of the most beautiful and intellectual heads in the world".

Her work was sometimes criticised for its soft focus, marks and imperfections, but as she said; “When focussing and coming to something which, to my eye, was very beautiful, I stopped there instead of screwing on the lens to the more definite focus which all other photographers insist upon.

Like many artists before and since, trial, error and luck played their parts in her success.

Julia Margaret Cameron's photographs, techniques & letters

Films produced by Cultureshock Media for the V&A.

Cameron's use of soft focus contributed to her success. Over time, she learned how to manipulate daylight by using roller blinds and extended exposure; in 1865 she began to experiment with a larger camera, and soon migrated to the large format permanently.

Cameron would corral her staff, family and visitors to sit for her and in stern tones demand that they pose perfectly still. Though her technique may have been criticised, her composition was celebrated. Stylistically, she consciously emulated the classical masters Raphael, Rembrandt and Titian in her use of light and shade.

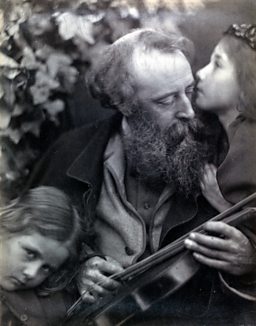

Her 'Fancy Subjects' are costume scenes, staged from myth, folklore and the theatre with the help of friends and staff. The tableaux are typical in their Victorian contrivance but strangely warm and guileless; later critics such as Roger Fry, a core member of the Bloomsbury group, remarked how such works were "unconscious of the abyss of ridicule which they skirt" while praising them as "touching and heroic".

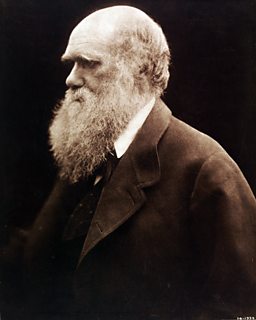

The Camerons' home was a gathering place for the intelligentsia of the day: poets Robert Browning and Henry Taylor; painters George Frederic Watts and William Holman Hunt; scientists Charles Darwin and Sir John Herschel; authors Lewis Carroll and William Makepeace Thackeray; art collector Lord Overstone; actress Ellen Terry; historian Thomas Carlyle; and explorer William Gifford Palgrave.

Many of these would sit for Julia's camera, so that the photographs created a record of the famous of her day.

These soirees were a precursor to the Bloomsbury group, not only in their intellectual curiosity but also because of their familial connections.

One of Cameron’s regular photographic subjects was her niece Julia Jackson, mother of Virginia Woolf and painter and interior designer Vanessa Bell. Both Jackson and Woolf would later write about their illustrious relative.

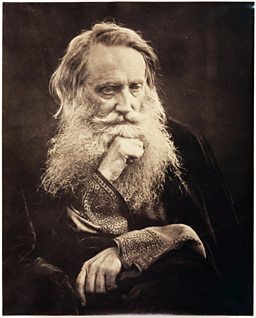

Henry Taylor, a Portrait, 1865

Cameron's portraiture is striking. The distinguished gentlemen who came to the Cameron soirees are powerful. Titans of the age, captured and framed.

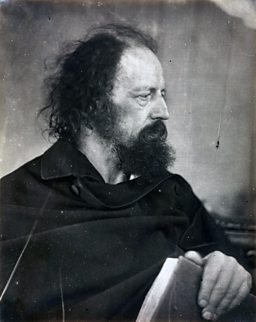

Tennyson, who called Cameron's sitters her "victims", declared Alfred Tennyson with Book, 1865 as being his favourite portrait, calling it the ‘Dirty Monk’.

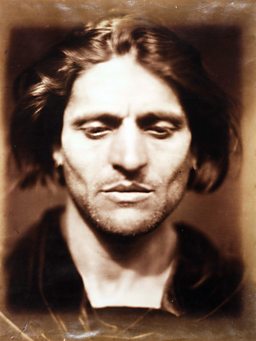

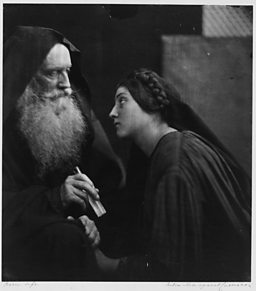

One image is particularly memorable, brooding and timeless. From the Herschel Album (1864) on show at the Science Museum, Iago, Study from an Italian, 1867, is all angular cheekbones, lowered eyes and a sharply contoured face.

In 1875 a downturn in Charles's financial fortunes led to the Camerons emigrating to Ceylon, where four of their five sons lived. This marked the effective end of Cameron's photography career - the climate proved difficult and processing chemicals were hard to find.

Cameron rarely photographed there, and she died in 1879. Charles died the following year. They are buried together in the churchyard at Glencairn, Ceylon.

Years later, photography historian Helmut Gernsheim did much to popularise her work in his 1948 book, Julia Margaret Cameron: Her Life and Photographic Work. This attention helped to cement her position as one of the most important photographers of the 19th century.

Julia Margaret Cameron is at the Victorian & Albert Museum until 21 February 2016.

Julia Margaret Cameron: Influence and Intimacy is at the Science Museum until 28 March 2016.

Iago, 1867

There is debate over who actually sat for Iago. Originally he was identified as Angelo Colarossi (c1838-1916), a professional model, from a family of professional models. Interestingly, his son posed for the statue ‘Anteros’ (now simply known as Eros) in Piccadilly Circus. However recent research points to the possibility that it may be Alessandro di Marco, model for Sir Edward Burne-Jones. Whoever he was, his skill lay in holding himself perfectly still for the extended exposures required.

Alfred Tennyson with Book, 1865

Whisper of the Muse, 1865

Prospero and Miranda, 1865

More photography from BBC Arts

-

![]()

War and peace

The compassionate photography of Don McCullin.

-

![]()

Childhood in the 1970s

Tish Murtha’s tender photos of deprivation in Britain.

-

![]()

Neon dreamland

Liam Wong's sci-fi-style images of Tokyo at night.

-

![]()

Pup art

William Wegman's Polaroids of his loyal Weimaraners.

-

![]()

Stanley Kubrick

1940s New York through the lens of teenage Stanley Kubrick.

-

![]()

Jailhouse Rock

Behind-the-scenes photos of Johnny Cash's prison shows.

-

![]()

The real Sin City

Hard-boiled photographs tell the history of crime in LA.

-

![]()

10 years with Kate Bush

Rare photographs of the singer at the height of her career.

More from BBC Arts

-

![]()

Picasso’s ex-factor

Who are the six women who shaped his life and work?

-

![]()

Quiz: Picasso or pixel?

Can you separate the AI fakes from genuine paintings by Pablo Picasso?

-

![]()

Frida: Fiery, fierce and passionate

The extraordinary life of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, in her own words

-

![]()

Proms 2023: The best bits

From Yuja Wang to Northern Soul, handpicked stand-out moments from this year's Proms