Conscription: the choice you couldn’t make

Marking the return of Radio 4’s wartime drama Home Front, we get an opportunity to explore the facts and myths of WW1 conscription.

In response to growing casualties from the front line Parliament introduced conscription in 1916, a controversial measure intended to strengthen forces. Prime Minister Asquith was forced to make concessions in order for the bill to pass, such as ensuring people could appeal on grounds of conscience, but it still led to the resignation of Home Secretary Sir John Simon. Many had seen it as a badge of pride that the UK army had up until this point been entirely voluntary and driven by patriotism, whereas Germany had to force people to fight for them.

Over three million men volunteered to serve in the British Armed Forces during the first two years of the World War One, before conscription was introduced. The Military Service Act of January 1916 specified that single men between the ages of 18 and 41 were liable to be called up unless they were widowed with children, or ministers of religion. Conscription came into effect on 2 March 1916. It was extended to include married men on 25 May, and by the end of the war the age limit had been raised to 51.

Grounds for appeal

Appeals against conscription were extremely controversial. One of the myths surrounding those that appealed was that the majority were conscientious objectors: in reality, there were only 16,000 ‘conchies’. 750,000 men appealed in the first 6 months through tribunals, which were held locally, mostly on grounds of hardship, family circumstances or because they considered their jobs indispensable. Their employer or a family member might also apply on their behalf. They could also be represented by someone at the hearing, for example William Bond from the No Conscription Fellowship often spoke on behalf of COs at the Newton Abbot Tribunal, Devon. Of the 750,000 applying a large proportion was successful, but this might only be an exemption for a couple of months after which they’d have to reapply. Getting an absolute exemption was extremely rare.

Accounts of conscription appeals are difficult to find, as local authorities were advised to destroy the paperwork after the war, but there is no doubt that the tribunals had an extremely difficult job. They had to assess a man’s fitness for service and compare it with his usefulness to the UK’s economy, as well as listening to some heartrending pleas from desperate parents. A widow in Croydon asked if her eleventh son could remain to help her in the house – the other ten were all serving in the armed forces. Similarly, the son of an East London man was given a three-month exemption from active service as his eight brothers were already overseas fighting.

In rural areas farmers could be exempted as they were working on the land and this also caused discontent among farm workers who were conscripted. In Devon there were rumours amongst labourers that older farmers would transfer their farms to their sons to protect them, even if they didn’t work on them. When asked at a tribunal what he’d do if a German tried to violate his sister or mother, the writer Lytton Strachey reputedly said, “I would try to come between them”.

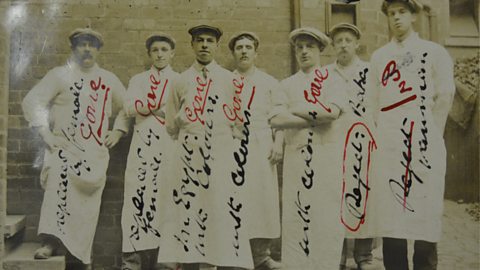

Rare archives shed new light on conscription

Staffordshire Archivist Matthew Blake on the people who appealed against being called up

Treatment of conscientious objectors

Choosing to be a ‘conchie’ was not something anyone took lightly. Abused in the street and often disowned by their families, these were men who felt compelled to put their pacifism or religious beliefs above the law. The tribunals also had to be seen to be hard on them, even humiliate them, in order to prevent people from following suit. The press would also pillory them, dedicating huge chunks of space to tribunal reports, which is probably why they’re over-represented in historical accounts.

Around 7,000 pacifists agreed to perform non-combat service, which usually involved working as a stretcher bearer in the front-line, which itself had an extremely high casualty rate. Absolutists were the 1,500 men who refused all compulsory service and ended up being drafted into units and court-martialled when they refused to obey orders. Some of the absolutists were transferred to France and some to prisons in England, such as Dartmoor in Devon, where they faced appalling conditions; 69 absolutists died in English prisons.

A typical ‘conchie’ story was immortalised in one of Britain’s most popular comedies: ‘Private Godfrey’s War’, which was set during WW2. Comedy Dad’s Army deals with the benign platoon medic’s war history as a ‘conchie’ being revealed, and his rejection by the rest of the men. They then discover that he had actually been a stretcher-bearer, and saved lives in the Somme and was decorated for bravery.

This was a poignant storyline for the actor Arnold Ridley, who played Private Godfrey. He himself had been discharged from the British army in August 1917, having received serious injuries to his hand and leg. Walking down the street later that year, he was approached by a woman who handed him a white feather, the war-time symbol of cowardice. He took it without comment, saying afterwards that he had ‘not wanted to advertise the fact that I was a wounded soldier’. He had been carrying his discharge badge in his pocket. Ridley then went on to fight in the World War Two, an ordeal he found it practically impossible to talk about as he felt so overwhelmed by the awful memories.

A plaque commemorating conscientious objectors who died in war can be seen at 1 Peace Passage, London, N7 0BT.

-

![]()

Listen to Home Front

Home Front is set in Devon between 4 April and 27 May 1916 and from 18 June to 10 August 1918.

More From Home Front

-

![]()

Home Front Season Seven Trailer - Devon

Listen to the trailer for season 7 which explores the impact of conscription on a farming community.

-

![]()

Rare archives shed new light on conscription

Staffordshire Archivist Matthew Blake on the people who appealed against being called up.

-

![]()

Download the Home Front Podcast

Keep up to date with every episode and subscribe to the Home Front podcast.