Seven Things for the Organist to Do While Counting Bars in The Planets

Holst’s The Planets with Prof Brian Cox - Live from the Barbican, the BBC Symphony Orchestra celebrates the exact centenary of The Planets premiere.

There’s an organ part in “The Planets”? Yes there is!

The organ is an important element in the huge palette of orchestral colours that Holst brings to bear in his “Suite for Large Orchestra”, although he deploys it very sparingly and some conductors even treat it as optional. Just once or twice, Holst calls on the organ to add its substantial weight to the full orchestra. Elsewhere, he asks for the quietest, deepest bass notes, sounding almost sub-sonically below delicate instrumental textures. Just once, he writes an extraordinary upward-sliding flourish; almost unique in organ literature.

A full performance of “The Planets” lasts around 50 minutes and the organ appears in fewer than 50 bars throughout. That’s barely 2 minutes of playing time, leaving the organist with an awful of lot spare time during the concert.

Here are our suggestions for some ways an organist might usefully occupy all those empty bars’ rest.

Plan a trip abroad

Holst, like numerous others, volunteered for service when war erupted in 1914, but the composer was short-sighted, sickly and forty years old.

He was rejected by the recruiting officers and pronounced unfit for active duty. He retreated to his sound-proofed music room at St. Paul's Girls' School in Hammersmith, where he taught, and his country cottage in Essex, and worked on the orchestration of his latest work: “The Planets”.

It was 1918 before Holst finally succeeded in being sent abroad on war work: to develop musical activities at training and internment camps “throughout the field of war”. A month before Holst crossed the Channel to begin his new job, “The Planets” had a first private performance in its orchestral version.

The organist’s job in the first movement, “Mars - the bringer of war” is to add weight to the big climaxes. You need to keep one foot free to operate the “swell pedal” and make the crescendo effect Holst calls for here. There are plenty of bars rest in between to discreetly browse that travel guide, though.

Write a horoscope for someone you know

“Venus” is a good eight minutes long and doesn’t feature the organ at all, so this is the ideal moment to brush up on your star-signs and planets.

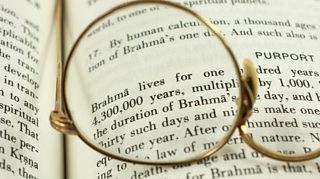

Holst was introduced to astrology by his friend Clifford Bax (brother of the composer Arnold Bax), and was intrigued. He had always been attracted to unconventional ideas; the more exotic and fantastical the better. Astrology came on the back of Theosophy, Indian Mythology and Vegetarianism!

He picked up a book "The Art of Synthesis" which described the astrological characteristics of every planet, and now his musical interest was piqued too. His daughter Imogen insisted that, “horoscopes had nothing to do with the writing of “The Planets”, and once he had taken the underlying idea from astrology, he let the music have its way with him.”

Nevertheless, in later years, Holst loved to indulge his “pet vice” of casting horoscopes for his friends. If anyone in the audience sees you writing, they’ll just assume you’re changing the fingering for your next entry.

Learn a new language

“Mercury – the winged messenger” also has no music for the organ, giving you time to learn at least a few phrases in a foreign tongue.

Holst himself was led to study languages after reading a book on Indian mythology: “Silent Gods and Sun-Steeped Land” by R.W. Frazer. Holst was inspired to seek out the original sources to which Frazer referred. He went to the British Museum Reading Room and asked for the “Vedas", the “Upanishads” and the “Bhagavad Gita”.

Alas, he discovered they were all written in Sanskrit and he couldn’t read a word. Holst eventually tracked down some English translations but found their renditions of these great works terribly bland. There was only one thing for it – he would learn Sanskrit himself and make his own versions. He never became fluent but he could get along well enough with a dictionary – and opened up for himself a whole new world of ideas, philosophy and stories.

Find a new piece to learn

Holst spurns the organ yet again in his fourth movement, “Jupiter”.

At this point the organist might be wondering why they bothered to turn up at all! We suggest using the time to explore a lesser known version of “The Planets” that features keyboard throughout.

Holst’s first version of his suite was scored for piano duet – before he expanded it onto the orchestral canvas we know today. He needed to put a keyboard version down on paper because he suffered from neuritis in his arm, which meant he often couldn’t play through his own composition sketches. Two colleagues at St. Paul’s Girls’ School would come in on Saturday mornings to play through this piano version for Holst, and help him make notes for the full orchestral score.

Holst conceived the final movement, “Neptune”, not for pianos but organ – four hands at one keyboard. He felt the mysterious sound world of that movement was much better suited to the organ. The score is tricky to get hold of but a facsimile of Holst’s own handwritten version is available – so grab a friend and dive in!

Sort out your pension plan

Holst’s own favourite movement was “Saturn, the bringer of old age.”

After all the mischief of Mercury and Jupiter’s high spirits, this is a stern reminder that the clock is relentlessly ticking. Every moment, another second is lost forever. Each heartbeat is another step on the road to oblivion.

Not surprisingly, this is the bleakest of all the movements although it ends in comfort and peace - and perhaps that’s a clue to what Holst loved about it. Unlike most of the other movements in “The Planets”, this is more than a simple “mood” piece. Holst takes us on a profound journey; expertly manoeuvring us from the creeping foreboding of the beginning into genuine terror and a horrific moment of crisis. And then… we’re out to the other side, moving through exhaustion, consolation, and finally beautiful, blessed relief. Maybe another way of interpreting this movement is a journey from youthful ignorance, through the fires of experience, towards wisdom. And what could be wiser than planning a future free of the worries of today?

For the organist, only feet are required in this movement, leaving the hands free to discretely browse all those comparison websites for the perfect pension package. Just don’t let the conductor catch you at it!

Polish your fingernails

There are 220 bars rest to count before the first organ entry in the 6th movement, “Uranus”.

After that, the organist is directed to literally pull out all the stops. We’re talking full organ here. The job is to slide your fingers swiftly up the keyboard, taking in every key, from the very bottom of the keyboard to the highest note. It’s called a “glissando” and it can be murder on the fingernails. Say goodbye to any expensive nail polish.

Pianists, harpists and string players may scoff, “glissandos aren’t really so tough”, they’ll tell you. Well, try it on an antique keyboard that’s individually operating thousands of pipes all at the same time, using mechanical pivots, levers, springs and valves that might have been installed a century or more before you were born! Perhaps that’s why Holst’s glissando is pretty much unique in mainstream organ literature. The effect can be stunning, though. Listen out for it at the big climax about two-thirds of the way through the six-and-a-half minute movement.

Make friends with the Chorus

The female chorus in “The Planets” has even less to do than the organist, appearing only in the final movement, “Neptune”.

The singers are concealed off-stage, their hidden voices materialising within the music as if from some other dimension. The choristers are usually gathered in some backstage corridor, out of sight from the other performers. But if you’re lucky, they might be hidden in the organ gallery, or very nearby. It might even be the organist who is charged with relaying the conductor’s beat to the off-stage singers.

Once again, only feet are needed for this movement – a single low A flat on the quietest 16 and 32 foot pipes.

Organists and singers are natural bedfellows. Often quite literally, actually – just ask Bach and his wife. Holst’s own father was an organist and his mother a talented soprano. Young Gustav followed his parents’ lead, taking organist’s jobs at several different churches in Gloucestershire and London and also conducting a variety of choirs. These included the Hammersmith Socialist Choir where Gustav met and fell in love with Isobel, who he eventually married.

Maybe there are couples out there today whose eyes first met across the organ loft, during a performance of “The Planets”!

Holst’s The Planets with Prof Brian Cox - Live from the Barbican, the BBC Symphony Orchestra celebrates the exact centenary of The Planets premiere.

-

![]()

Music of the Spheres

A collection of programmes and features about the planets and other heavenly bodies.

-

![]()

Choir and Organ

Choir and Organ: Every Sunday at 4pm Sara Mohr-Pietsch presents an irresistible mix of music and singing; with a monthly programme devoted to recorded performances of the best organ music.

-

![]()

Five things you'll know if you play the organ

We're offered insight into the world from the view of the organist's bench.