Shock of the hue: How Scotland's artists sought adventures in colour

6 January 2016

In an ambitious four-part series for BBC Four, artist and presenter LACHLAN GOUDIE explores 5,000 years of Scottish art from the Neolithic to the present day. The programmes examine the social and political history of Scotland and the events that influenced the artistic imagination. In this BBC Arts feature, Goudie considers how the willingness of many of Scotland’s artists to look outward underpinned the development of Scottish art.

Scots, as a people, have never stayed put. By necessity or by choice they have always had to travel in order to secure their livelihood or develop their ideas.

The same spirit that motivated the Scottish adventurers, soldiers and engineers who made such a disproportionate impact on the building of the empire, prompted Scottish artists to become part of a larger cultural diaspora, seeking out inspiration and instruction in the most exotic places.

Scottish artists were seeking out inspiration and instruction in the most exotic places... It was by travelling abroad that they carried the seeds of radical change back to Britain

And it was by travelling abroad, and absorbing new ways of thinking about art, that they carried the seeds of radical change back to Britain.

William Allan (1782-1850) had been the first of a long line of Scottish artists to undertake extraordinary journeys to foreign lands.

In 1805 he embarked upon a ten-year venture which took him across Russia to the Ukraine.

When Allan returned to Edinburgh he filled his studio with an exotic haul of treasures and memorabilia collected en route.

His friends David Wilkie and David Roberts were inspired by their intrepid colleague to undertake their own travels.

Roberts became the pre-eminent lithographer of the age. The prints he produced following long journeys across Africa and the Middle East were enormously popular, helping to define how the Victorians viewed the world beyond Dover.

Scotland’s earliest art

Lachlan Goudie explores how Scotland’s early inhabitants marked their landscape with art.

Arthur Melville, like many of his Glasgow contemporaries, went to study in Paris. He took lessons, at the famous Académie Julian, under flamboyant tutors like Meissonier, Duran and Bougereau.

It is Melville who recalibrates the colour balance of Scottish art for the next generation of innovators

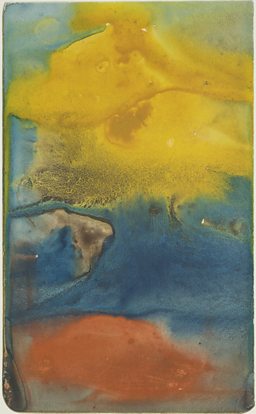

There he learned to paint in watercolour, experimenting with new techniques; soaking the paper and dropping pure pigment over his line drawings. He absorbed the ambience of the café and cabaret culture around him, and discussed the radical new ideas that were fermenting in the Paris art world.

The watercolours he later produced, like Dancers at the Moulin Rouge, are a testament to the fact that he understood the profound lessons of Impressionism before any other British artist.

In 1880 he embarked upon a two-year journey in the footsteps of Allan, Wilkie and Roberts, travelling across the Middle East in search of the sun. He suffered heartbreak, illness, banditry and was even arrested for being a spy.

But the greatest story of his travels was the way in which he learned to handle the colour of the Orient and express it through a loose and instinctive watercolour technique.

His approach was derided as ‘loose, blottesque and stainy’ by critics. The name stuck and Melville’s ‘blottesque’ painting style became his signature.

In watercolours like The Little Bullfight it allowed him, abstractly, to suggest a frenzy of movement, activity and heat. By contrasting areas of pure colour and paper bleached in Chinese white, he could summon up the power of Mediterranean sun.

England had always prided itself in being the home of elegant watercolour painting but Melville was the greatest British watercolourist of the age.

When these paintings were viewed in Scotland, by a public for whom a trip to Loch Lomond was the height of exoticism, the effect was dazzling. Melville’s confidence, originality and willingness to experiment and paint with pure sunlight was an example to all of his contemporaries.

It is Melville who recalibrates the colour balance of Scottish art for the next generation of innovators; he is the link between the tonal approach of the Glasgow Boys and the expressive use of colour that characterised the next chapter in the story of Scottish art.

-

![]()

Your Paintings

Browse a slideshow of 18 paintings by Arthur Melville

Paris at the turn of the 20th Century was the crucible of the avant-garde; a city where the fault-lines of art history were grinding together.

These young Scottish artists found themselves at the very heart of the action, on hand to observe the somersaults of Post-Impressionism at the exact moment when they were first exploding onto the stage

The most dramatic upheavals in contemporary art were taking place here, and the latest tremor to shake the Parisian art-scene were the paintings of the Fauves - Henri Matisse and André Derain - who shocked audiences with their use of a wild and blazing colour palette.

France by now was well established as a keystone for Scottish culture – much more than it had ever been in England.

So it was not unusual when, in 1899, a 16-year-old Scot named Francis Cadell arrived at the Académie Julian to study painting. His parents had been advised by Arthur Melville himself to send their son to Paris, and Cadell followed closely in the footsteps of his compatriot Samuel Peploe.

These young Scottish artists found themselves at the very heart of the action, on hand to observe the somersaults of Post-Impressionism at the exact moment when they were first exploding onto the stage.

The Story of Scottish Art

-

![]()

On BBC Four & BBC iPlayer

Episode one in Lachlan Goudie's series is on BBC Four, Wednesday 6 January 2016 at 8pm

I am the product of a particularly Scottish tradition in painting, encouraged by my dad to spend 18 months living in Paris, just as Cadell had done.

These early Scottish pioneers of the avant-garde were alive to the revolutionary possibilities of contemporary art

I attended life-drawing classes at the Beaux-Arts and painted my way around the French capital. I sought out paintings by Matisse and Derain whose free handling of paint and use of bright, unmixed colours had such an impact on the Parisian Scots of the early 1900s.

I was merely following a tired and well-trodden path, but these early Scottish pioneers of the avant-garde were alive to the revolutionary possibilities of contemporary art, experiencing the shock of the new, learning and experimenting.

The Scots' compunction to venture abroad in search of inspiration, however, has, historically been counterbalanced by the lure of home. Throughout their lifetimes Peploe, Cadell (and colleagues, Leslie Hunter and J.D. Fergusson) travelled extensively across France.

They explored the Cote d’Azur and the ports of the Mediterranean, frequenting artist hotspots mapped by their Fauve predecessors. But there was always a homecoming. The creatively fertile soil of Scotland’s landscape kept drawing them back.

On their return home these artists, brought the palette of the Fauves to bear upon the Scottish landscape. And it was as a result of these canvasses that they would ultimately become identified as the ‘Scottish Colourists’.

Friends Cadell and Peploe regularly journeyed together to the Hebrides and particularly to Iona.

On that extraordinary island, where the traditions of Scottish art were first nurtured, where the Book of Kells was illuminated with its rainbow of colours, they created paintings that redefined the public’s perception of what Scotland looked like.

- The Story of Scottish Art begins Wednesday 6 January 2016 at 8pm on BBC Four.

- Arthur Melville | Adventures in Colour is at the Scottish National Gallery until 17 January 2016.

- A version of this article was originally published in October 2015, when the series was first shown on BBC Two Scotland.

On BBC iWonder

How did artists create a stereotype of Scotland?

For many, Scotland’s dramatic landscape has become a kind of cultural shorthand for bravery, purity and integrity. But how did they create such an enduring vision of the country? Lachlan Goudie explores the Scottish stereotype in this exclusive iWonder Guide.

Related Links

More from BBC Arts

-

![]()

Picasso’s ex-factor

Who are the six women who shaped his life and work?

-

![]()

Quiz: Picasso or pixel?

Can you separate the AI fakes from genuine paintings by Pablo Picasso?

-

![]()

Frida: Fiery, fierce and passionate

The extraordinary life of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, in her own words

-

![]()

Proms 2023: The best bits

From Yuja Wang to Northern Soul, handpicked stand-out moments from this year's Proms