For three decades, a bizarre offender has racked up dozens of court appearances and several spells in prison over a strange fetish that drives him to touch young men's muscles.

Across the North West, Akinwale Arobieke has become a modern-day bogeyman and an internet sensation, and now a court order that curtailed his activities has been lifted.

One April afternoon, as James Vaughan walked through Garston, in south Liverpool, on his way to play snooker, a voice called out to him. Did he know if there were any gyms nearby?

Vaughan turned to look. Next to him, by an alleyway fence, was a man he didn’t recognise - an imposing, powerfully built figure.

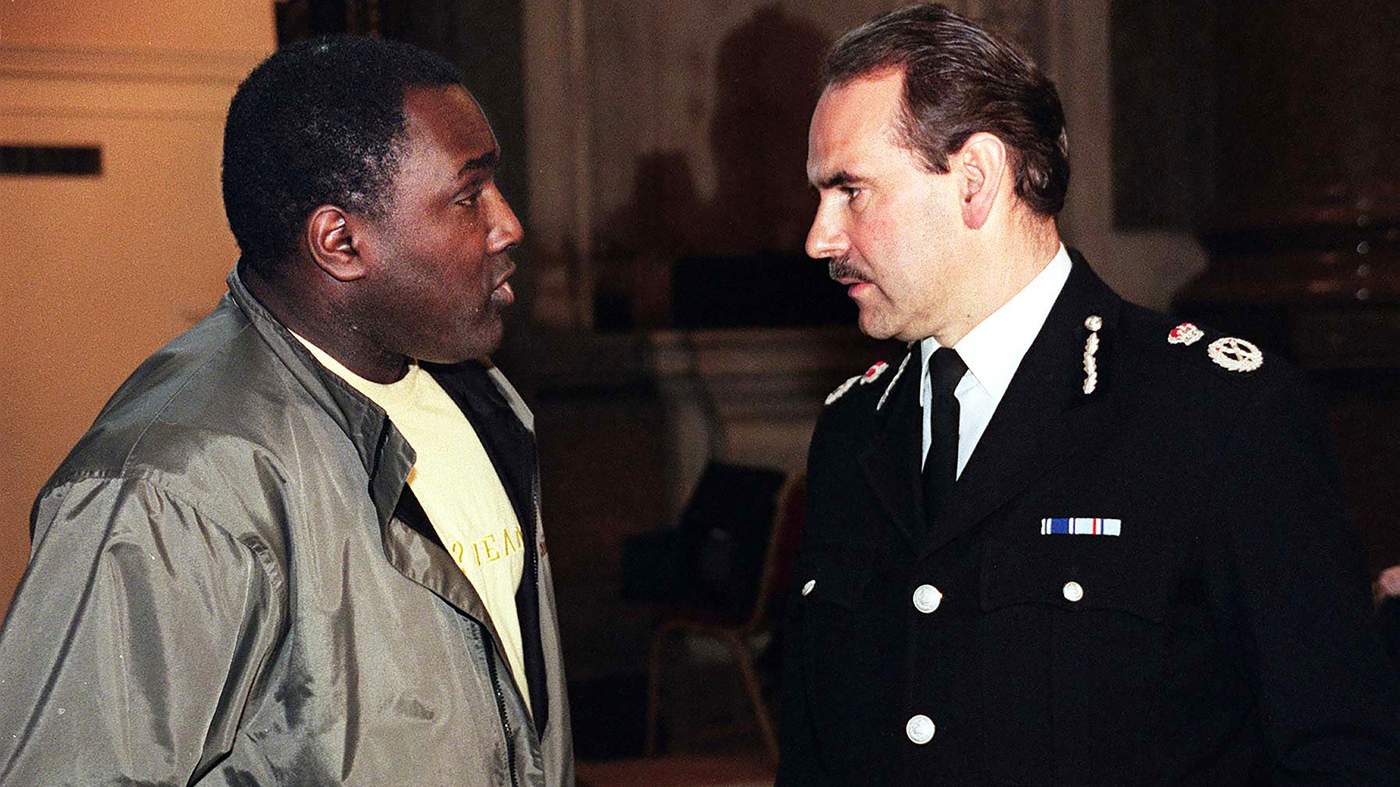

James Vaughan, pictured here in the 1980s

At the time Vaughan was 15, maybe 16, and, at 6”3’, tall for his age. But this man was an inch or two bigger still, and muscular - he must have weighed over 20 stone (127kg).

The man stood in front of Vaughan, blocking his path, and asked: “Can I feel your muscles? Can I feel your biceps?”

The sheer oddness of the request threw Vaughan. He was a reserved, shy boy, and there was no-one else around to ask for help.

So when the man ordered him to flex his muscles, Vaughan did what he was told.

The man gripped each of his arms in turn. “It was sort of slimy, running his hand up and down,” Vaughan, who is now 48, recalls.

Vaughan saw a chance to get away. When a stranger passed on the other side of the road, the teenager pretended it was his father and latched on to him.

Vaughan finally arrived at the snooker hall and told a friend what had happened.

“Do you know who that was?” the friend said. The man who accosted him was notorious. He had a thing for feeling muscles. And a nickname: “It’s Purple Aki.”

For years, stories about this bogeyman swirled around Merseyside.

The tales varied, but they agreed on certain key details - that he was huge and that he liked to feel young men’s muscles. Sometimes he would measure them too.

Parents would tell their children not to stay out after dark or Aki would get them.

Older siblings would pass on tales to younger brothers and sisters, and these would circulate around playgrounds, growing more lurid with each telling.”

It seemed like a bizarre fairy tale, borne of 1980s neuroses about sexuality and race. The nickname itself was racially charged - the suggestion being he was “so black he’s purple”.

Aki had surely been conjured up somewhere in the deepest recesses of the Scouse id. Plenty of people assumed he was an urban legend, a bit like the Candyman in Liverpool-born author Clive Barker’s short story.

But there were plenty of people who’d swear blind they knew a cousin or a neighbour who’d been squeezed by him, or who’d had to run away from him.

And a select few would assure you there really was a man, and they’d met him. His name was Akinwale Arobieke.

It was the early 1980s and Tony Evans was 23, working in a warehouse near Liverpool’s Albert Docks. It was a hard job, loading heavy bundles of Littlewoods catalogues into lorries.

One day, as he climbed a flight of stairs from the loading bay, a voice behind him asked if he did weights.

Evans turned around, and there he was. About a year previously Evans had been told stories about Aki by his younger brothers, who were athletes and regular gym-goers. Back then, Evans had thought the tales were hilarious. But he’d never really believed them. Until now.

“I bet you’ve got big biceps.” The voice was softly spoken. A hand reached towards Evans.

Evans snarled a retort. He'd throw this man down the stairs if he didn't back off.

The interloper retreated, and disappeared through a door. He hadn’t appeared aggressive at any point. But the bogeyman was real.

Over the next year or so Evans saw a lot of him around the site.

“He was very deferential, very quiet, spoke very, very softly. He didn't draw attention to himself unless he wanted to feel your muscles,” Evans says. “When he was in the loading bay he was almost soundless coming up.”

Lorry drivers from out of town would sometimes let him have a squeeze and everyone in the warehouse would laugh.

Not everyone found him amusing. One hot July day, Evans stood at the loading bay and watched as Arobieke sprinted towards him from the other side of a high fence. “About 20 guys with bare chests and pickaxe handles were after him. I'm sure they would have killed him,” Evans says. He watched Arobieke scale the fence to escape.

Evans knew from his brothers there was a real fear of Arobieke around sports clubs and gyms. His notoriety was spreading.

As the internet age arrived, the swirl of rumours gave way to fact. Local newspaper reports of Akinwale Arobieke's regular appearances in court would be gleefully swapped online, and embellished in the process.

It wasn’t always easy to tell where Arobieke the man ended and Aki the myth began.

On messageboards and social media, people would post anecdotes about Aki hanging around gyms and rugby league clubs. Even athletes and weightlifters were terrified of him.

There was a clear pattern in the stories. He’d get them to squat while he lay on their back facing downwards, squeezing their quads or calves.

It made many of them feel deeply uncomfortable.

And there were colourful rumours – that his father was a High Court judge, or Nigerian royalty, or that Aki himself had some kind of shady connections with Liverpool’s underworld.

A story circulated that he would approach his victims and ask: “Pop or slash?” He was supposedly giving them a choice between rape or having his initials carved on to them.

The tale was ridiculous and completely untrue, but it added to the burgeoning Aki mythology.

But while some found him frightening, plenty of others saw him as a figure of fun.

At the 2008 Glastonbury festival, someone brought a banner bearing the legend “arr mate!!! Purple Aki jus’ gripped us in a Portaloo”, below a photo of Arobieke’s baleful-looking mugshot.

At the same event in 2013, there was a flag that read “Purple Aki - the gym pest from the North-West”.

Glastonbury 2008: Aki had become the stuff of social legend

(Cherrie Chik/Instagram)

Football banners referenced him, at both Liverpool and Everton games.

People wrote songs and made cartoons about him and posted them on YouTube. In June 2012 Merseyside Police had to issue a statement quashing rumours on Twitter that he had died.

Aki had gone viral.

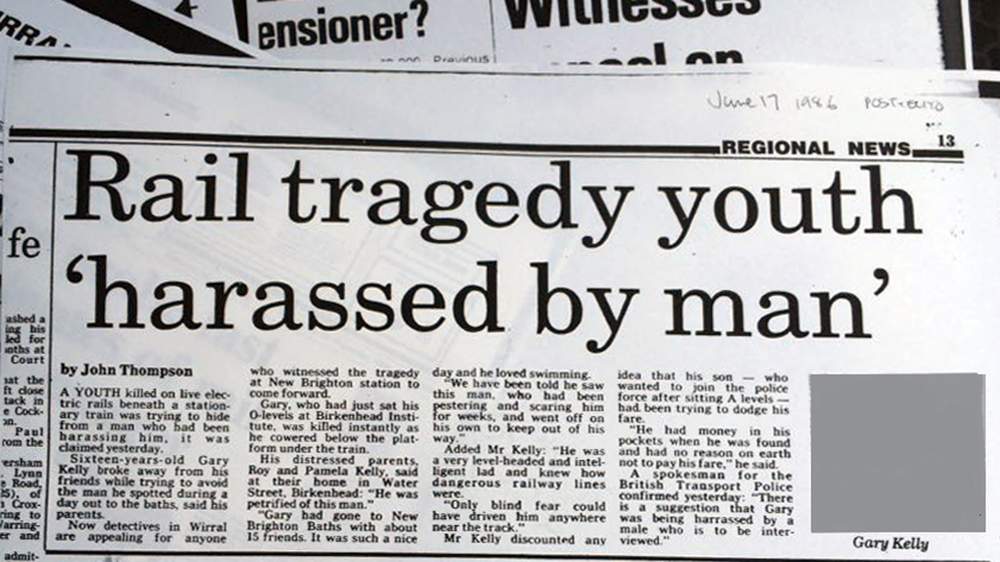

But amid all the tall tales, there was a much darker story. Back in the 1980s, it was said, a boy had died on a railway line while running away from Arobieke.

This story was different. It was true.

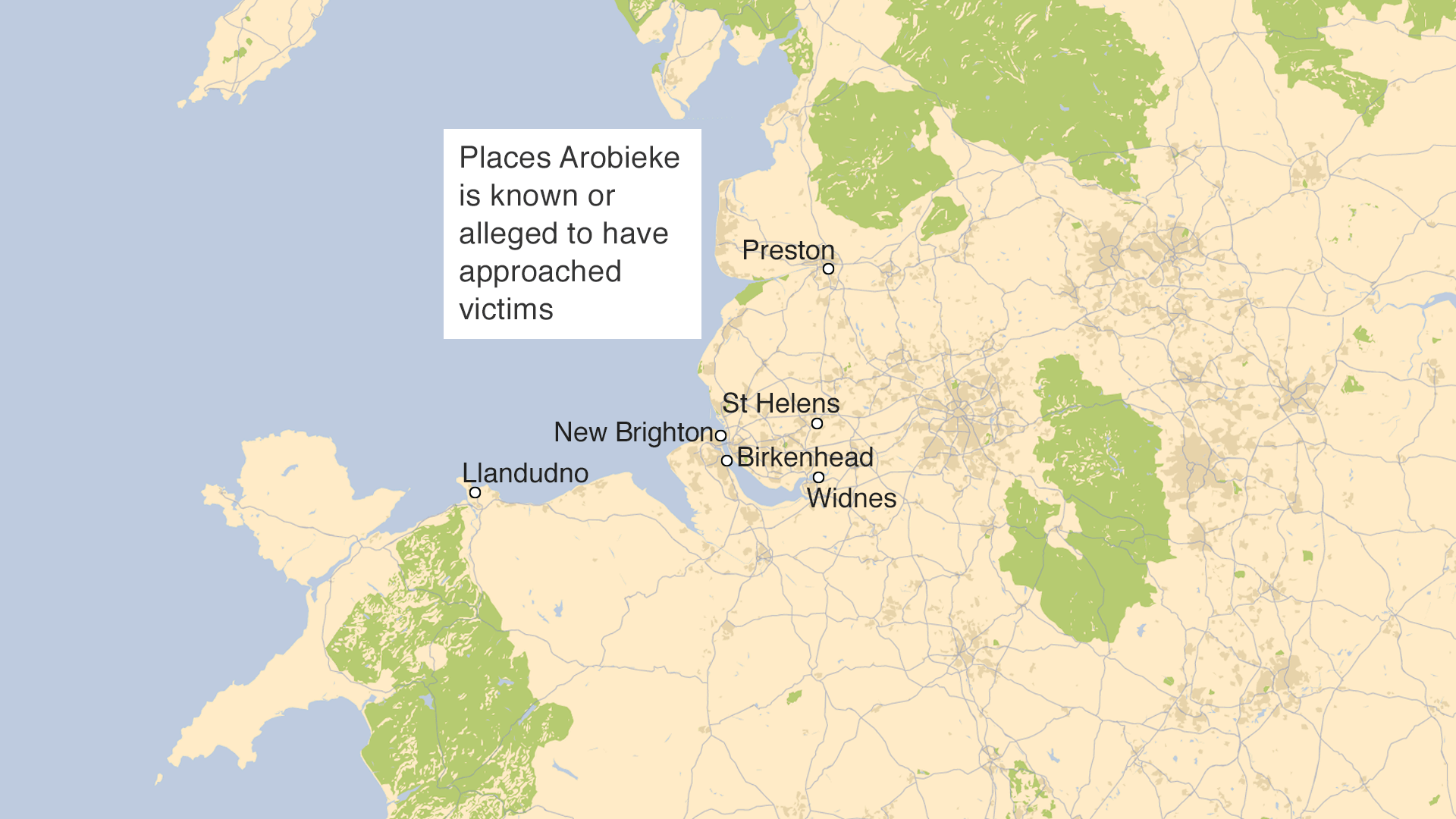

Sunday 15 June 1986 was a bright, warm day in New Brighton, one of the busiest the Merseyside seaside resort had seen that year. At the local pool, 16-year-old Gary Kelly had spent the afternoon with a crowd of about 15 friends. Gary had just finished his O-levels, and loved to swim.

He was 6ft tall, athletic, a talented footballer. The home he shared with his parents and two younger brothers in nearby Birkenhead was filled with trophies he’d won at Eastham and District Junior League and Shaftesbury Boys’ Club.

He supported Manchester United, and had been scouted by Newcastle. But Gary’s ambition was to join the police after finishing his A-levels.

Level-headed, intelligent, forward-thinking – those were the adjectives his dad Raymond, a builder, and mum Pamela used to describe him. He’d been going out with his girlfriend, Elaine Jordan, whose parents ran a pub near his home, for 18 months.

Late in the afternoon, the group of friends made their way out of the pool.

And then a cry went up: “Aki’s here.”

It was Arobieke, then aged 25. At the sight of him, Gary abandoned his companions and fled.

Gary was terrified of Arobieke, a court would later hear. The teenager had been subjected to a campaign of harassment by him, a prosecutor told jurors. Rodney Klevan QC added that Arobieke had stalked and threatened to kill Gary, who told police he had been assaulted.

In the four months previously, Gary’s personality had changed from happy-go-lucky to that of a frightened boy constantly looking over his shoulder, the court heard.

Gary first encountered Arobieke outside his school, Elaine says. Another time, when Gary was on his way back from visiting Elaine, he saw Arobieke waiting for him outside his front door. Arobieke would also wait at the stop where the school bus would drop him.

“You’d look round and he’d be there standing next to you,” Elaine recalls. “He could just appear like that. Everyone knew of him.”

Arobieke would ask Gary about his muscles, Elaine says. She adds that he would get Gary to tense the muscles in his leg before he gripped them. Then he would tell Gary to squat and, according to Elaine, Arobieke would bend over his back, feeling his calf muscles.

Gary feared what Arobieke would do to him, Elaine says.“Kids mocked Gary and said: ‘Aki will shag you. You are Aki’s new boy,’ that sort of thing.”

On one occasion, Elaine and Gary were waiting for a bus when Arobieke turned up at the shelter. “He got on our bus and followed us. I started having a go at him. He called me a silly cow.”

On that Sunday afternoon, when Gary abandoned his friends and fled, he must have had “terror in his heart and mind”, the judge told jurors at Liverpool Crown Court.

Gary thought he could hide in New Brighton’s railway station, a few hundred yards from the baths. He concealed himself for a while on a stationary train before walking along the platform towards the ticket barrier. And then he saw Arobieke.

No-one saw Gary’s last movements. But the court heard he climbed off the platform under a train, where he touched a live rail. Gary was electrocuted.

Elaine was at home in the bath when she heard the news. One of her neighbours shouted through the window that something had happened. Next she heard screaming. Gary’s dad had called from the hospital to say he was dead. Elaine’s mother came upstairs and broke the news to her.

Elaine was three months pregnant with Gary’s child.

In May 1987, Arobieke was found guilty of manslaughter and jailed for two-and-a-half years. The judge said it was one of the most unusual cases he had ever heard. He ordered a further 12 alleged offences of indecent assault and assault causing actual bodily harm to lie on file.

Gary’s father told the Liverpool Echo the sentence was “disgraceful”. Graffiti went up around the Wirral: “RIP Gary Kelly.”

Arobieke appealed against the conviction. In November 1987 three judges ruled that his mere presence at the station was not an unlawful act of harm. The conviction was overturned. Arobieke was a free man. In 1989 he was reportedly awarded £35,000 in compensation.

For 12 months after the death, Elaine says, she did nothing but cry. In January 1987, their daughter Jamielee was born. As Jamielee grew up she asked questions about her dad. Elaine told her he was in heaven.

In March 1997, the Sunday People newspaper ran a story about Arobieke. “6ft 5in giant stalks rugby super league stars," was the headline.

It claimed warnings had been issued to all 12 Super League clubs after a three-year campaign in which Arobieke attacked players’ houses, vandalised their cars and made violent threats. The paper alleged that he had taken a 6ft, 17-stone (108kg) prop, thrown him over his shoulder and performed squats.

After the story ran, Arobieke launched a libel action against the paper, but it was dropped after one and a half days in court.

It was to be the first in a series of regular court appearances over nearly two decades.

In the spring of 2000, Kelly Mullaney saw a strange man hanging around her brother near their home in Widnes, Cheshire.

“He sees the boys when he's going to the local shop,” she says. “Coming up to him: ‘Can I feel your muscles? Do you work out at the gym?’”

Mullaney says she told Arobieke to leave her brother alone or she’d call the police. Later, Arobieke turned up at Mullaney’s house with what she believed to be a gun. “He put it through the letterbox,” she recalls. “He was shouting into the letterbox.”

Mullaney, terrified, rang 999.

Within minutes, she says, police cars filled her street. Arobieke was arrested and later charged with making a threat to kill. There was no evidence that the object was in fact a gun, but he was jailed for 30 months at Warrington Crown Court on 3 August 2001.

So scared of potential retribution was Mullaney she went into a witness protection programme, relocating to another part of England. “I left all my family and my friends,” she says.

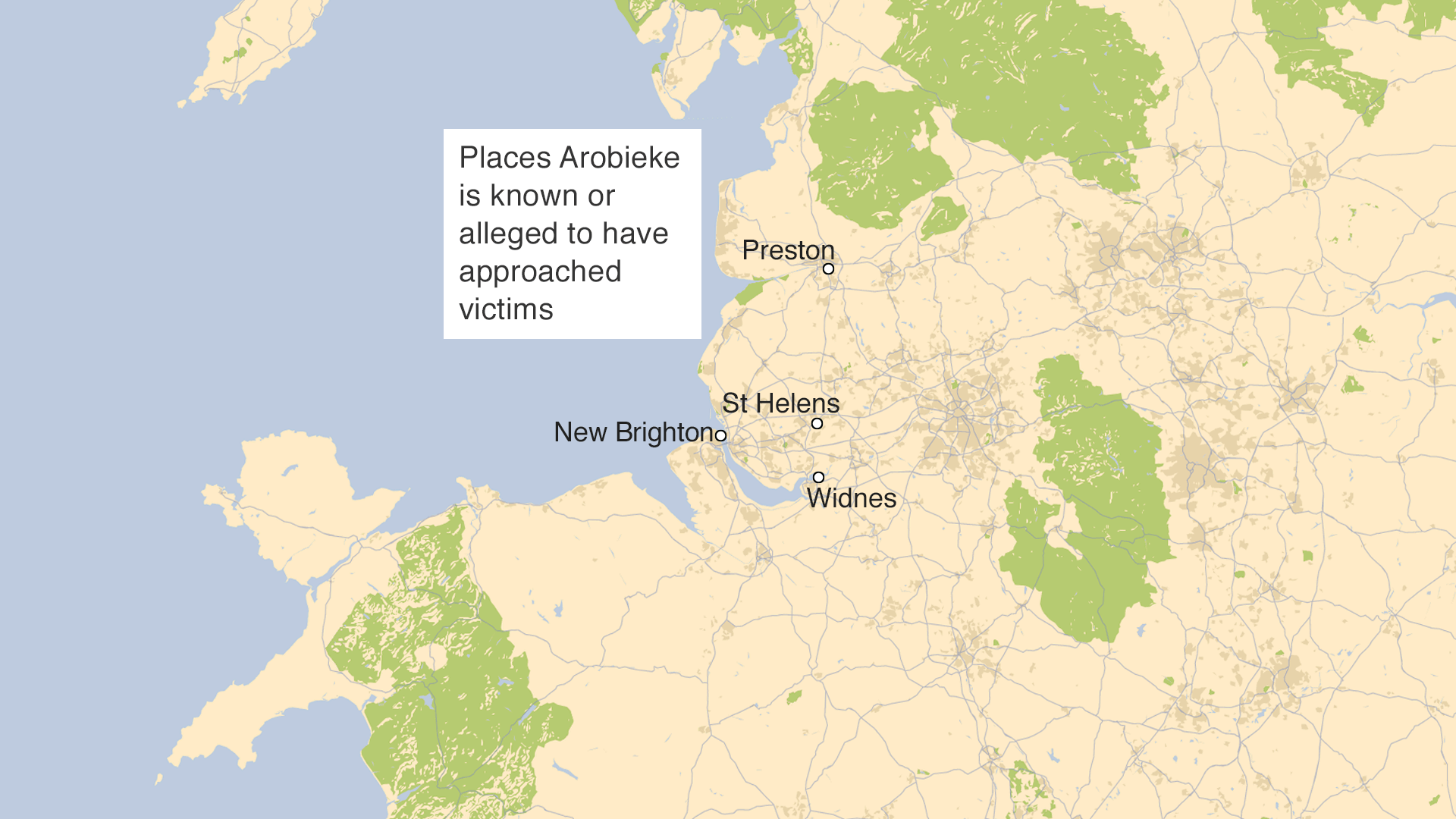

Merseyside Police launched an investigation into Arobieke - Operation Ice. Detectives interviewed 123 people from Newcastle upon Tyne to South Wales, although much of the inquiry focused on the area around Warrington and St Helens. When approached to discuss the investigation for this article, Merseyside Police declined to comment.

Operation Ice established a pattern of behaviour. Arobieke would approach young men at gyms, sports clubs and colleges and ask to feel their muscles. Some he asked to squat.

Arobieke would also ask young men to stand with their arms extended in a "scarecrow" position, and then lift them from behind. He would also use a tape measure to measure their calves, thighs and chest.

What also stood out was the detailed research Arobieke carried out into the lives of those he targeted, as well as his persistence. “He would turn up everywhere our son went and knew information about where he lived and details about us and the rest of his family,” the parents of one boy from St Helens told a local newspaper. Like Mullaney and her partner, the family went into a witness protection programme.

According to testimony later given in court, officers who searched Arobieke’s home found photos of muscular young men. They also discovered a “stalker’s manual” with an index of victims’ contact numbers and other personal details. There were also hand-written notes with body part measurements.

On Monday 15 December 2003, Arobieke was jailed for six years at Preston Crown Court after pleading guilty to 15 counts of harassment and another of witness intimidation. An additional 61 alleged counts, mostly of indecent assault, were left to lie on file. The judge also issued 31 restraining orders banning him from contacting any of the young men named in the case.

Sentencing Arobieke, Judge Edward Slinger told him: “You are a danger to young men and your behaviour is both strange and obsessive.”

Jail didn’t stop reports coming in of strange behaviour from Arobieke. Years later, a court was told that fellow inmates complained he had asked to measure their biceps with a shoelace. At another hearing it was claimed that he was moved 14 times while in prison, but Arobieke insisted this had been the result of unfounded allegations.

According to his birth certificate, Akinwale Oluwafolajimi Oluwatope Arobieke was born on 15 July 1961 at Manchester’s Crumpsall Hospital.

His mother’s name was listed as Abisola Aduke Arobieke, a secretarial student from Catherine Road, Manchester. No father’s name or occupation was given. The birth was registered on 17 August 1961.

At the age of six months he was placed in care and he spent time in a Barnardo’s home in Llandudno, Conwy, a defence barrister acting for him once told a court.

As a young man he went from job to job. At one stage he was a Mersey Tunnels cleaner, and later he worked as a city council messenger.

By the time of the trial over Gary Kelly’s death, he was living in Dingle, an inner city working-class area - best known as the birthplace of Ringo Starr - overlooking Liverpool’s waterfront. Its rows of back-to-back terraced houses were used as the setting for Alan Bleasdale’s Boys From The Blackstuff and Carla Lane’s Bread.

Later, after his release from prison, Arobieke moved to neighbouring Toxteth, the heart of Liverpool’s long-established black community.

Nothing is known about Arobieke that could easily explain his odd behaviour.

On his release from prison in 2006, after two years and 10 months, a court handed him a Sexual Offences Prevention Order (Sopo).

Sopos were introduced by the Labour government as part of the 2003 Sexual Offences Act on similar lines to the Anti-Social Behaviour Orders (Asbos), which were designed to tackle persistent low-level nuisance conduct. Sopos are civil orders, but breaching one is a criminal offence with a penalty of up to five years in prison.

The odder Asbos gained much media coverage (a woman banned from having sex with her husband too loudly, an 87-year-old instructed to turn down the volume of her Glenn Miller records, a man ordered to stop sniffing petrol on forecourts).

Arobieke’s Sopo banned him from touching, measuring or feeling muscles and asking people to do squat exercises in public; feeling muscles in private without consent; loitering around or going into gyms and sports clubs; talking to anyone under 18 on purpose; entering a school or university without permission; driving or being a passenger in any car other than a taxi; leaving Merseyside without the chief constable’s permission; and entering St Helens, Warrington or Widnes without police permission.

He had not actually been convicted of any sexual offences, although a number of allegations of sexual assault had been ordered to lie on file.

In court appearances, Arobieke has always denied getting any kind of sexual gratification from feeling muscles.

When he was jailed in 2001, Arobieke accepted his behaviour could cause fear but told the court he believed he had a genuine friendship with the young men he approached.

In 2007 Judge Bruce Macmillan, sitting with two magistrates, rejected Arobieke’s request to overturn the Sopo, saying: "It is clear his touching of boys and young men is motivated by sexual urge." The following year the interim order was made permanent.

During one 2008 hearing, Arobieke admitted that he had an "unusual interest in muscles, the development of muscles and the potential of young men to improve their physique". He said he had allowed an exercise routine to "get out of hand. It became an obsession".

Many of those who have been squeezed by him believed at the time his motivation was sexual.

There has been discussion of fetishes of similar kinds. In a 2008 almanac of sexual paraphilias by Dr Anil Aggrawal, sthenolagia is defined as sexual arousal from the display of strength and muscles.

But very little is known about it, says Mark Griffiths, professor of behavioural addiction at Nottingham Trent University.

There are thousands of websites devoted to “muscle worship”, Griffiths says. Typically, muscle-worshippers tend to like being dominated by women or men who are more muscular than themselves.

But Arobieke is usually at least as big and strong as those he has approached – often much more so. It’s not clear to Griffiths how to describe Arobieke’s interest in muscles. “This doesn't fit the stereotype,” he says.

In November 2007, Arobieke was sent back to prison. He’d breached the Sopo by travelling to Preston, Lancashire, approaching a man in a shopping centre and touching his bicep, a court heard.

Arobieke appealed against the Sopo once again. During a hearing in May 2008, he “behaved erratically” in court and “seemed volatile”, the Liverpool Daily Post reported. At one point he left the dock and began questioning the judge, the paper said. At another he “walked out of court clutching a carrier bag, before returning five minutes later and sitting at the back”.

Later, he apologised to his victims and told the court he was “infamous, notorious, everything from a bogeyman to whatever”.

Psychiatric counselling had helped him realise that "if I am towering over them, and I am a big black man, they may not be being really consenting, they may be consenting out of fear." In future, he promised he only wanted to feel the muscles of those who genuinely consented to him doing so.

But lawyers acting for Merseyside Police said the Sopo should stay in place. The court was told Arobieke had followed one bodybuilder all the way to Tenerife, and of how he would confront his victims with details such as their father's car registration number or sibling's place of education.

The judge upheld the Sopo.

Arobieke was jailed for a second breach of the order in April 2009. Liverpool Crown Court heard he had approached a 17-year-old in the street in Birkenhead and tried to touch his bicep. The boy said he was left feeling “frightened and sick”.

The following year he was sentenced to a further two-and-a-half years in prison for touching the muscles of a boy in Llandudno, North Wales. Arobieke, who defended himself in court, insisted he was the victim of malicious false allegations to the police: "They receive several calls a day saying I am in locations across the country even when I am in prison."

But after serving that sentence, Arobieke started to have more success in court.

In August 2013 he was cleared of breaching his Sopo by squeezing muscles in Manchester city centre, Bolton and Trafford. Arobieke, once again defending himself, told the court he was the victim of a “modern-day witch hunt”.

Officers had approached one alleged victim, a 16-year-old boy, at his home rather than waiting for him to come forward, Arobieke noted. He was cleared of all charges by a jury.

Then, in October that year, a trial involving Arobieke, who was accused of harassing a Greater Manchester Police officer at a bodybuilding competition, collapsed amid criticism of the officer's conduct outside court. A spokeswoman for the force declined to comment when approached for this article.

During the trial, David Faulkner, a wrestler and mixed martial arts fighter, approached Arobieke for a selfie. Arobieke invited him to come to court. Faulkner was impressed by his fluency and grasp of the law: "He's very well spoken. He knows exactly what he's saying.”

The two subsequently became friends. “I think he's terribly misunderstood,” says Faulkner. “Obviously I do agree with the majority of civilisation that his antics are strange. But a lot of it is conjecture.” The stories about him had grown like “Chinese whispers”, Faulkner says.

After his acquittal, Arobieke told the Liverpool Echo he had spent over two years on remand awaiting charges that were either dropped or of which he was found not guilty. Further charges against him were dropped in April 2014.

He was found guilty of breaching the Sopo again in 2015. The court heard he had met a student on a train from Manchester Piccadilly to Colwyn Bay, asked him to flex his muscles, and then if he could measure his bicep.

Arobieke had called himself “Andy”. The young man didn’t know who he was until he read an online article about a month later, jurors were told.

During the trial, Arobieke complained about the use of the “racist” term “Purple Aki” in prosecution papers. They would not refer to a Chinese person as "Yellow Wong", he said. The Wirral Globe newspaper had previously given an undertaking that it would not refer to him by his nickname after Arobieke told the Press Complaints Commission he considered it “racist and offensive”.

In May 2016, a judge lifted the Sopo that banned Arobieke from feeling muscles.

It was at Manchester Crown Court. Arobieke told the court he had always been interested in young men, “but not in a sexual way”. While his behaviour had breached the court order, it was not criminal in its own right and was not sexual, he insisted.

Judge Richard Mansell QC said he wasn’t into bodybuilding himself. But he thought men who had muscles in their arms “the diameter of my leg” were the sort of men who were likely to admire other men’s bodies. “They don't build the body up to hide it under loose-fitting sweatshirts,” he said. “They are men likely to talk and weigh and measure each other."

The judge said that Arobieke acknowledged he was “interested in, indeed obsessed” with the musculature of men, and that his build and age were bound to instil “at least a feeling of unease in young males, if not fear”.

Nonetheless, he said, the “obsessive and intimidating” behaviour Arobieke had shown between 1997 and 2000, that had led to his original conviction, had not been repeated.

None of the recent complainants had formed the “slightest impression” that Arobieke had derived sexual gratification from their muscles. He hadn’t pursued or harassed them as he had in the 1990s. Unlike earlier incidents, Judge Mansell says, they hadn’t suffered physical or psychological harm.

The judge lifted the Sopo and gave him a suspended sentence for the incident on the train to Colwyn Bay. If Arobieke threatened, intimidated or harmed anyone he risked being brought back before the court, he was warned. But Judge Mansell said he was now free to “pursue your interest in bodybuilding and weight training” so long as he did so in an appropriate venue, like a gym or a bodybuilding event.

The judge referred to Gary Kelly. The stigma of his death still hung over Arobieke, he said.

Arobieke replied: “It's not nice in any way, shape or form to be involved in the death of another human being.”

He said he wanted to reinvent himself. “I want to bring my profile down. I don’t think the issue is me as a person, I think the issue is me as a profile.”

Perhaps with this in mind, Arobieke did not respond to multiple requests to put across his side of the story for this article.

But bringing down Arobieke’s profile won’t be easy. Not with all the banners and websites and memes.

One bar in Liverpool sells a cocktail called “Purple Aki Punch”. The ingredients are gold and dark rum, Cointreau, grenadine, passionfruit, orange, pineapple and lime.

There’s a gym in Birkenhead with a life-sized cardboard figure of a man with Arobieke’s face pointing his finger. At the base it says: “Memberships due.” Everyone who visits gets the joke.

But not everyone finds it funny.

Gary Kelly’s daughter Jamielee Jordan – now a successful nanny who works for wealthy families around the world – is one of them.

She used to travel through Toxteth on the bus, and she’d be terrified that Arobieke would get on board and somehow recognise her.

“It does upset me when I hear people joking about ‘Purple Aki’,” she says. “Since the internet he’s become a joke. It’s hard for me to hear. My dad lost his life.”

Others who’ve encountered Arobieke are furious that the Sopo has been lifted. To Vaughan, it’s a “disgrace”. Mullaney says she still lives in fear of Arobieke tracking her down.

Everywhere he goes, passers-by snap surreptitious pictures of Arobieke on their smartphones. The bolder ones go up to him and ask for selfies. Once the pursuer, he’s become prey himself.

In December 2015, Lord Sugar retweeted a photo of Arobieke and Faulkner, which a Twitter prankster had told him showed his dad and a friend on their way to buy the peer’s book. The retweet generated national press coverage.

Arobieke strongly dislikes the myth that’s grown up around him, Faulkner says. "He said to me that he's sick of it. He obviously doesn't like the name ‘Purple Aki’. It's just blatant racism that was rife in the 70s and the 80s.”

It’s significant that the legend of Aki took off during a decade in which racial antagonisms in Liverpool ran high, says Tony Evans, now a freelance sport journalist.

Riots in Toxteth in 1981 and 1985 had been sparked by tensions between the local black population and the police. “There were a lot of people had that fear of a big black man,” he says. “I think that was a factor for many.”

Aftermath of riots in Toxteth, Liverpool in 1981

Evans believes it’s not just Arobieke’s victims who have been let down by the authorities’ failure to understand and address his behaviour – it’s Arobieke himself, too.

“This was a fella who right from the beginning needed help,” says Evans. “He's a real guy with issues who the system has failed.”

Without the internet, Aki might well have remained a mythical figure, only tangentially related to the reality of Akinwale Arobieke. But social media has stirred up the fable with the real man. People continue to find him hilarious and terrifying in equal measure.

He isn’t a source of amusement to Elaine Jordan. Three decades on, she still dreams about Gary Kelly.

She used to dream that he’d never really died, that he’d been kidnapped and had come back, and she hated waking up afterwards - she’d feel down all day.

But now she loves it when he appears in her sleep. “You forget things. Then I dream about him and he is real again. It’s like he’s really there.”